Beyond the Hearth: Unveiling the Diverse and Enduring Roles of Women in Ancient Societies

When we conjure images of ancient civilizations – grand pyramids, bustling forums, epic battles – the figures that often dominate our mental landscape are kings, emperors, philosophers, and warriors. For centuries, historical narratives, largely penned by men, relegated women to the shadows, confining their roles primarily to the domestic sphere: child-rearing, housekeeping, and quiet subservience. However, a deeper excavation of archaeological evidence, legal texts, literary works, and artistic representations reveals a far more nuanced and dynamic reality. Women in ancient societies were not a monolithic group; their experiences varied dramatically across cultures, social classes, and time periods, often defying the simplistic labels assigned to them. From powerful priestesses and influential queens to skilled artisans and savvy businesswomen, their contributions were not merely supplementary but foundational to the very fabric of these foundational civilizations.

At the most fundamental level, the universal role of women across virtually all ancient societies was linked to reproduction and family perpetuation. In an era before modern medicine, high infant mortality rates and the constant need for labor meant that bearing and raising children, especially male heirs, was paramount. This biological function often dictated social structures, legal rights, and even religious beliefs. Women were seen as the vessel for the future, the link in the ancestral chain. This emphasis, however, did not always translate into disempowerment. In many societies, the ability to produce a strong lineage granted women a certain, often indirect, power within the family unit and, by extension, the community.

Let us embark on a journey through some of the most influential ancient societies to unravel the tapestry of women’s roles.

Egypt: A Land of Relative Equality and Powerful Queens

Ancient Egypt stands out as a civilization where women enjoyed a remarkably high degree of legal and social equality compared to their counterparts in other ancient cultures. Egyptian women could own property, inherit wealth, initiate divorce, conduct business, and even represent themselves in legal disputes. Marriage contracts often protected a woman’s assets, and divorce, while not uncommon, usually ensured she retained her dowry and a share of marital property.

Beyond the domestic sphere, Egyptian women could be priestesses, scribes (though rare), doctors, and craftswomen. They worked alongside men in the fields, markets, and workshops. This relative freedom culminated in the extraordinary rise of female pharaohs, a phenomenon almost unheard of elsewhere. Hatshepsut, who ruled as pharaoh for over two decades in the 15th century BCE, famously donned male attire and a false beard, not to deny her gender, but to fulfill the traditional iconography of kingship. Her reign was one of prosperity and monumental building projects. Later, Nefertiti, wife of Akhenaten, held immense power, possibly even co-ruling, and Cleopatra VII, the last pharaoh, was a formidable political and military strategist who commanded the loyalty of armies and the attention of Rome’s most powerful men. Her very existence as an independent female ruler challenged the patriarchal norms of the Roman world she interacted with.

The Greek historian Herodotus, observing Egyptian society in the 5th century BCE, noted with surprise: "The women attend the markets and trade, while the men sit at home and weave." While perhaps an exaggeration, it underscores the distinctiveness of Egyptian gender roles from his own Greek perspective.

Mesopotamia: Legal Codes and Economic Acumen

In the fertile crescent, the cradle of civilization, the role of women was more varied and often constrained by patriarchal legal codes, yet still offered avenues for influence and economic activity. The Code of Hammurabi (c. 1754 BCE), one of the earliest and most complete legal codes, reveals a society where women had specific protections and rights, albeit within a male-dominated framework. They could own property, engage in business, and testify in court. A woman’s dowry remained her property, and in cases of divorce, she could reclaim it. However, penalties for women (e.g., adultery) were often harsher than for men.

Despite these legal strictures, Mesopotamian women were active participants in the economy. They worked as brewers, weavers, millers, and even moneylenders. Some managed large estates, and aristocratic women could hold considerable power. The role of priestess was particularly significant, with high-ranking priestesses wielding considerable religious and political authority. Enheduanna, daughter of King Sargon of Akkad (c. 23rd century BCE), was the high priestess of the moon god Nanna in Ur and is considered the earliest known author in history, having penned hymns and poems that profoundly influenced Mesopotamian religion and literature. Her status was not merely ceremonial; she was a key political figure in her father’s empire.

Ancient Greece: The Tale of Two Cities

Nowhere is the diversity of women’s roles more starkly illustrated than in ancient Greece, specifically the contrast between Athens and Sparta.

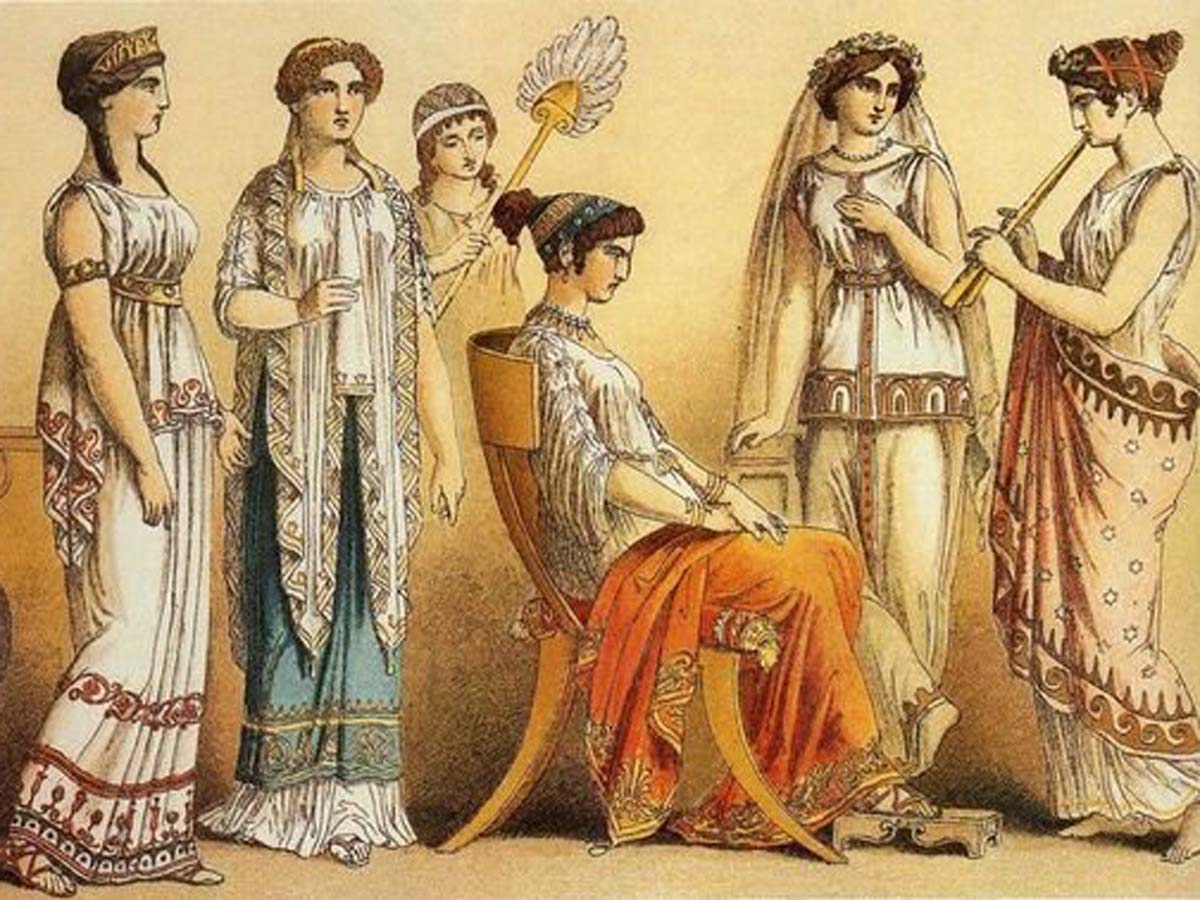

In Classical Athens, the birthplace of democracy, women, paradoxically, had very limited public roles and were excluded from citizenship. Athenian women, particularly those of the upper classes, were largely confined to the oikos (household), their primary duties being managing the home, overseeing slaves, and raising children. Their legal status was akin to that of minors, always under the guardianship of a male relative. They could not own property in their own right, participate in politics, or represent themselves in court. Public life was almost exclusively the domain of men. Philosophical figures like Aristotle reinforced this view, stating that "the male is by nature superior, and the female inferior; and the one rules, and the other is ruled."

However, even in Athens, there were exceptions. Hetairai – highly educated courtesans – often enjoyed more freedom and intellectual discourse than respectable wives. Figures like Aspasia, the companion of Pericles, were renowned for their intelligence, wit, and influence on Athenian intellectual circles, despite their non-citizen status. Poorer women, on the other hand, had more freedom of movement out of necessity, working in markets, nursing, or small crafts to support their families.

In stark contrast, Spartan women enjoyed considerably more freedom and respect. Valued for their role in producing strong, healthy warriors, they underwent rigorous physical training, including wrestling, running, and discus throwing, alongside men. This was not for combat, but to ensure they were robust mothers. Spartan women could own and inherit property, and by the 4th century BCE, they owned a significant portion of Spartan land. With their husbands often away at war, they managed estates and held considerable authority within the household and community. Gorgo, wife of King Leonidas, was known for her intelligence and political acumen, famously quipping to an Athenian woman wondering why Spartan women ruled their men: "Because we are the only ones who give birth to men." While still excluded from political office, their economic power and social influence were unparalleled in the Greek world.

Ancient Rome: Matronly Influence and Legal Evolution

Roman society, while deeply patriarchal, offered women a complex and evolving set of roles and rights. The ideal Roman woman was the materfamilias, the dignified wife and mother who managed the household, educated her children, and upheld the family’s honor. While legally under the patria potestas (father’s power) of their father or husband, Roman women, particularly those of the elite, could exert considerable indirect influence.

As the Republic transitioned to the Empire, women’s legal standing gradually improved. With the rise of marriage sine manu (without husband’s hand), a wife remained legally tied to her father’s family, retaining control over her dowry and inheriting from her father. This gave many Roman women significant economic independence. They could own businesses, manage finances, and even engage in legal disputes through male representatives.

Powerful women like Livia Drusilla, wife of Emperor Augustus, wielded immense political influence behind the scenes, shaping imperial policy and succession. Cornelia Africana, daughter of Scipio Africanus, was celebrated as an exemplary Roman matron, renowned for her intellect and devotion to her sons, the Gracchi brothers.

The Vestal Virgins were a unique and powerful group of priestesses dedicated to the goddess Vesta. They held a sacred and vital role in Roman religion, guarding the eternal flame that symbolized the city’s prosperity. Given immense privileges, including the right to own property, make a will, and be free from patria potestas, they were highly respected and influential figures, despite their celibacy and confinement to their duties.

Beyond the Mediterranean: Global Perspectives

While the scope of this article focuses on the classical civilizations, it’s crucial to acknowledge that women’s roles were equally diverse across other ancient societies. In ancient China, Confucian philosophy emphasized filial piety and the subservience of women, yet powerful empresses like Wu Zetian defied these norms, reigning as the only female emperor in Chinese history. In Vedic India, women enjoyed more freedom and education, with female scholars and poets (like Gargi Vachaknavi) participating in philosophical debates. Later periods, however, saw increased restrictions. In the pre-Columbian Americas, Mayan and Aztec women were vital to agriculture, weaving, and religious rituals, with some holding positions of power or influence within their communities or as priestesses.

Conclusion: Essential Threads in the Tapestry of Time

The historical record, once read through a more inclusive lens, reveals that women in ancient societies were far from passive bystanders. While the pervasive patriarchal structures often limited their public agency and legal rights, their roles were indispensable. They were the primary caregivers, educators, and spiritual guides within the family. They were crucial economic contributors, whether through agriculture, weaving, trade, or craft production. They were priestesses who mediated between humanity and the divine, and in exceptional cases, they were queens and regents who shaped the destinies of empires.

The challenge for historians continues to be piecing together the lives of the "invisible" women – the countless wives, mothers, laborers, and artisans whose daily contributions, though rarely documented in grand histories, formed the bedrock of ancient life. Their voices may often be silent in the surviving texts, but their fingerprints are everywhere: in the pottery they made, the fabrics they wove, the children they raised, and the traditions they preserved. By acknowledging and exploring the multifaceted roles of women, we gain a more complete, vibrant, and accurate understanding of the complex tapestry that was ancient human civilization, recognizing that their strength, resilience, and ingenuity were as essential to its flourishing as any emperor’s decree or warrior’s sword.