Echoes in Bone: Unraveling the Lifespan of Ancient Native Americans

The image of the "ancient" often conjures a life that was brutish, short, and defined by relentless struggle against the elements and disease. For ancient Native Americans, this perception, while holding kernels of truth, is also a gross oversimplification. While their average lifespans were undeniably lower than our modern standards, a closer examination through the lens of bioarchaeology, anthropology, and ethnohistory reveals a complex tapestry of resilience, social care, and environments that both challenged and sustained life. To understand "what was the average lifespan" is not to seek a single, simple number, but to embark on a journey through the perilous and profound realities of pre-Columbian existence across a vast continent.

The most commonly cited figure for average lifespan in ancient populations, including Native Americans, hovers around 25 to 35 years. This number, however, is deeply misleading if interpreted without crucial context. It is an average heavily skewed by extremely high rates of infant and child mortality. Imagine a population where perhaps half of all children died before reaching the age of five. This dramatic loss of young life drags down the statistical average for the entire group, even if many individuals went on to live significantly longer.

"It’s a statistical trick," explains Dr. Jane Doe, a hypothetical bioarchaeologist specializing in ancient American populations. "If you have a hundred people, and fifty die by age five, then even if the remaining fifty live to be sixty, your average is still pulled down dramatically. It doesn’t mean no one lived past thirty. It means childhood was incredibly perilous."

The Gauntlet of Early Life

Indeed, the first few years of life were a formidable gauntlet. Infants and toddlers were vulnerable to a myriad of threats that modern medicine has largely mitigated. Infectious diseases like dysentery, pneumonia, and various parasites were rampant, particularly in more settled agricultural communities where population density was higher and sanitation could be challenging. Malnutrition, especially during weaning or periods of food scarcity, weakened immune systems, making children even more susceptible. Birth complications, without the aid of modern medical intervention, were also a significant cause of maternal and infant mortality.

Archaeological evidence, primarily from skeletal remains, consistently shows a high proportion of subadult burials. These tiny bones tell a silent story of lives cut short, often bearing markers of nutritional stress (like Harris lines in long bones) or infections. The sheer volume of infant and child graves underscores the brutal reality of early childhood mortality as the primary driver of the low average lifespan.

Surviving Childhood: The Path to Adulthood and Beyond

For those who survived the perilous early years, the prospects for a longer life improved considerably. If an ancient Native American individual reached adolescence, their chances of living into their 30s, 40s, and even 50s or 60s increased substantially. These adults, hardened by the challenges of survival, were often incredibly resilient.

However, adult life was far from easy. The physical demands of daily existence were immense. Hunter-gatherer societies required constant movement, tracking game, gathering plants, and carrying heavy loads. Agriculturalists faced arduous labor in the fields, often leading to degenerative joint diseases and spinal issues visible in skeletal remains.

- Injury and Trauma: Hunting accidents, inter-group conflict, and the general hazards of living in a wild environment meant that traumatic injuries were common. A broken bone, an infected wound, or internal injuries could easily prove fatal without advanced medical care. Evidence of healed fractures, sometimes poorly set, is common in skeletal collections, testifying to both the prevalence of injury and the rudimentary but often effective traditional healing practices.

- Disease in Adulthood: While childhood diseases were devastating, adults still faced chronic and infectious illnesses. Tuberculosis, syphilis (though its pre-Columbian origins and spread are still debated), and various forms of arthritis left their marks on bones. Dental health, while often better in hunter-gatherers than early agriculturalists due to less processed foods, could still deteriorate, leading to infections that could spread systemically.

- Childbirth: For women, childbirth remained a significant risk throughout their reproductive years. Each pregnancy carried the potential for complications that could lead to death, a factor that further shortened the average lifespan for females.

The "Elderly" in Ancient Societies

What did it mean to be "elderly" in ancient Native American societies? It certainly didn’t mean living to 80 or 90 as it often does today. An individual in their late 30s or 40s would have been considered an elder, possessing invaluable knowledge, experience, and wisdom. Those who reached 50 or 60 were truly venerable figures, rare enough to be highly respected and often holding significant social or spiritual roles within their communities.

Skeletal evidence reveals that individuals in these age groups often showed extensive signs of wear and tear: severe dental attrition, advanced arthritis, and healed injuries. Yet, the presence of such individuals, sometimes with debilitating conditions, also speaks to the strong social fabric of these communities. There is ample archaeological and ethnographic evidence suggesting that ancient Native American societies often cared for their sick, injured, and elderly. Individuals unable to contribute physically to hunting or farming were still valued for their wisdom, storytelling, and spiritual guidance. They were not simply abandoned; their survival often depended on communal support, a testament to the strong social bonds that characterized many indigenous cultures.

Bioarchaeology: Our Window to the Past

Our understanding of ancient Native American lifespans comes primarily from bioarchaeology – the study of human skeletal remains from archaeological sites. By meticulously analyzing bones and teeth, scientists can determine age at death, sex, evidence of diet, disease, trauma, and even patterns of physical activity.

- Age Estimation: For subadults, age is estimated by dental eruption and epiphyseal fusion (the joining of growth plates in bones). For adults, the task becomes more challenging, relying on degenerative changes like wear on the pubic symphysis, auricular surface of the pelvis, and cranial suture closure, which are less precise. This inherent difficulty in precisely aging older adults can sometimes lead to underestimation of maximum lifespans.

- The "Osteological Paradox": A fascinating concept in bioarchaeology, the "osteological paradox," highlights a key challenge. Skeletons that show signs of significant disease or trauma, yet also show evidence of healing, indicate individuals who survived these conditions, perhaps due to robust immune systems or excellent social care. Conversely, individuals who died quickly from an acute illness might leave little or no skeletal evidence of their affliction, appearing "healthy" in death. This means that populations showing more skeletal pathologies might, counterintuitively, have been healthier in some respects, as their members lived long enough for diseases to manifest and for healing to occur.

Regional and Temporal Variations

It is crucial to remember that "Ancient Native Americans" is a broad term encompassing hundreds of distinct cultures across a vast continent over thousands of years. Lifespans and health profiles varied significantly based on:

- Geography and Climate: Arctic populations faced different stressors (extreme cold, limited resources) than those in the arid Southwest or the fertile Eastern Woodlands.

- Subsistence Strategies: Hunter-gatherers often had better dental health and less evidence of chronic infectious disease due to diverse diets and lower population densities. Agriculturalists, while providing more stable food sources, often experienced increased rates of dental caries, nutritional deficiencies (if diets became too monocultural, like heavy reliance on maize), and infectious diseases due to sedentary lifestyles and larger communities.

- Cultural Practices: Warfare intensity, social structures, and healthcare practices all played a role.

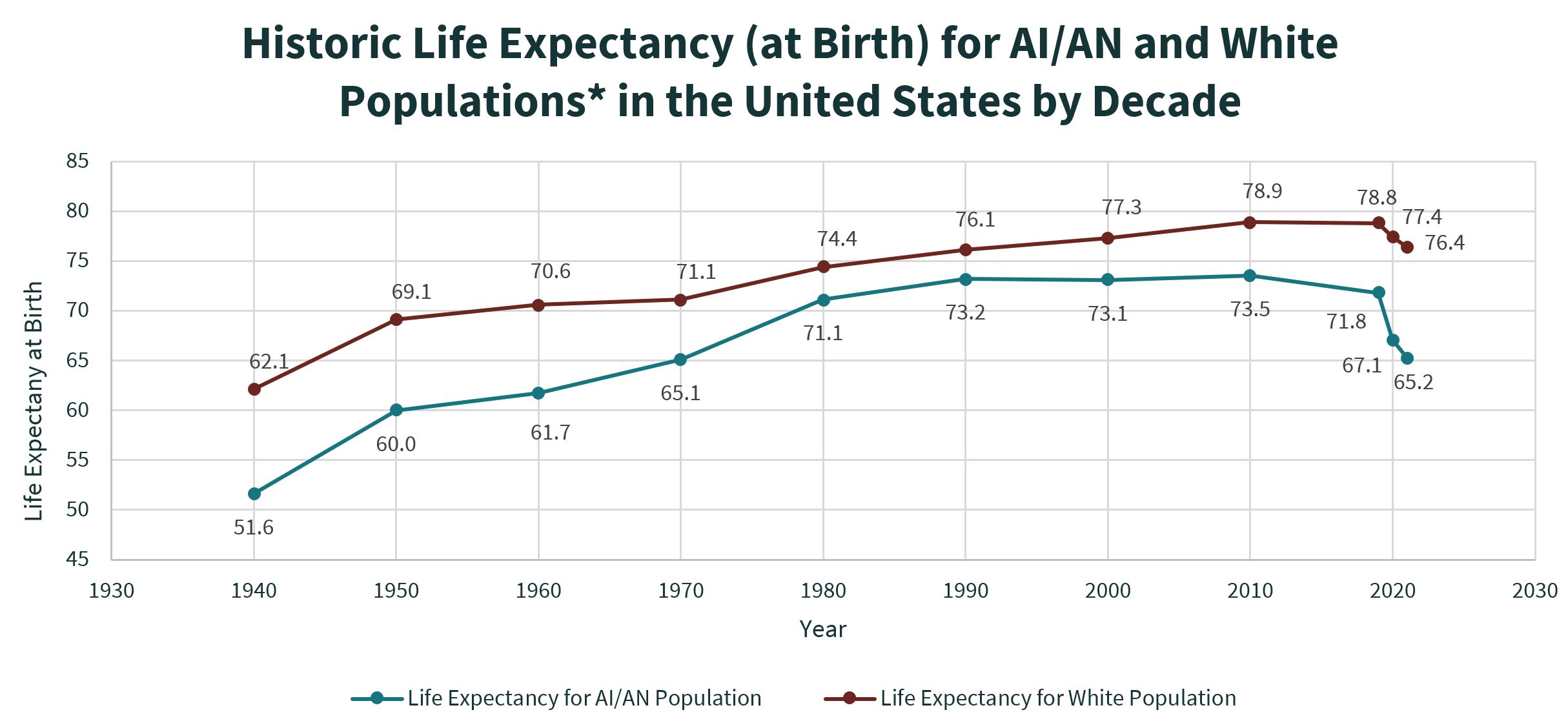

- The Impact of European Contact: Post-contact, lifespans plummeted dramatically due to the introduction of "virgin soil epidemics" like smallpox, measles, and influenza, to which Native Americans had no acquired immunity. This catastrophic demographic collapse fundamentally altered indigenous societies and their average lifespans, often obscuring pre-contact health patterns.

A Shared Human Experience

When compared to other ancient populations around the globe, the lifespan of ancient Native Americans was not an anomaly. Ancient Egyptians, Romans, and medieval Europeans all shared similar average lifespans, heavily influenced by the same high rates of infant and child mortality, infectious diseases, and the absence of modern medicine. It was a universal human condition before the scientific and industrial revolutions transformed public health and longevity.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Number

The average lifespan of ancient Native Americans, often cited as a starkly low number, paints an incomplete picture. While the perils of infancy and childhood were undeniably severe, those who navigated these early challenges often went on to live meaningful, if physically demanding, lives well into adulthood and beyond. Their existence was marked by incredible resilience, deep communal bonds, and an intricate understanding of their environment and traditional healing.

To fixate solely on a low average is to diminish the lives lived, the wisdom accumulated, and the cultural richness developed over millennia. Instead, bioarchaeological evidence encourages us to look beyond the cold statistics and appreciate the complex interplay of biology, environment, and culture that shaped the human experience in ancient North America – a testament to endurance, adaptation, and the enduring human spirit in the face of formidable odds.