Echoes of Silence: The Devastating Decline of Native American Languages

In the rich tapestry of human expression, language stands as a profound testament to identity, history, and worldview. For millennia, the North American continent pulsed with an unparalleled linguistic diversity, home to hundreds of distinct Native American languages, each a unique vessel of culture, knowledge, and ancestral wisdom. Today, this vibrant mosaic has been tragically diminished, with many languages teetering on the brink of extinction, their last fluent speakers dwindling with each passing year. The story of this decline is not one of natural evolution, but a complex and often brutal narrative of colonization, forced assimilation, and systemic oppression, leaving an indelible scar on Indigenous communities and humanity’s shared linguistic heritage.

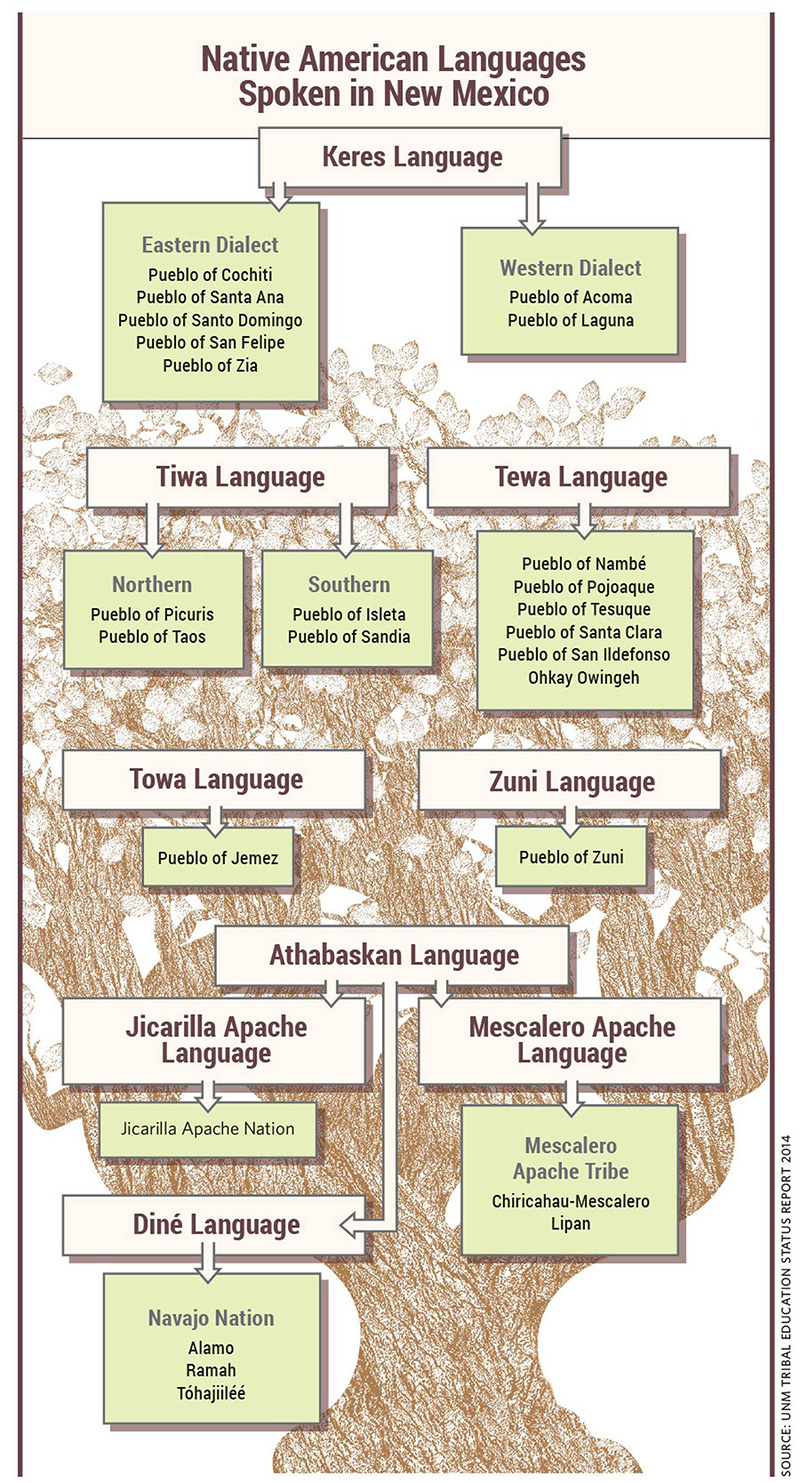

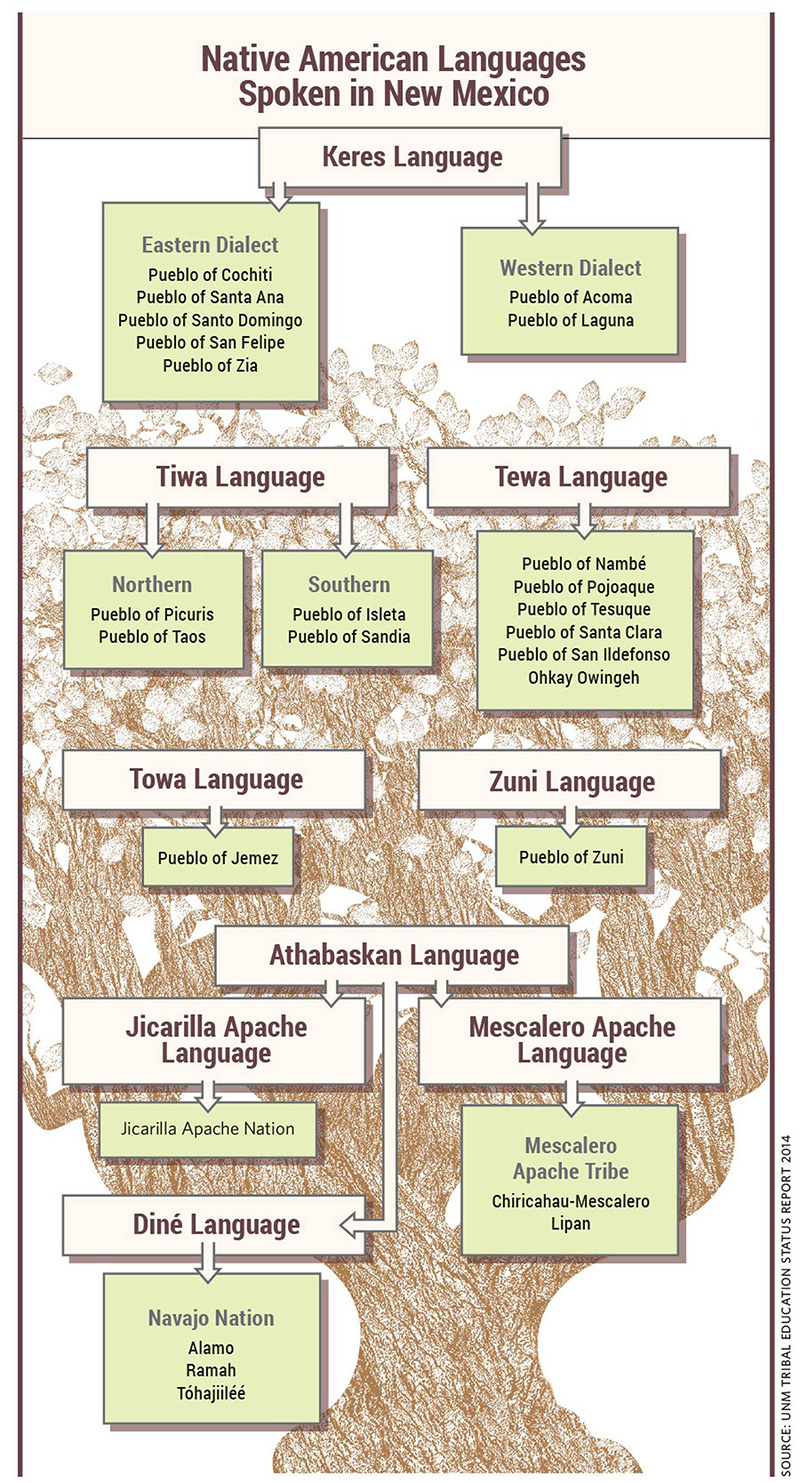

Before the arrival of Europeans, estimates suggest that between 300 and 500 distinct Indigenous languages flourished across North America. These languages were not mere tools for communication; they were intricate systems embodying unique philosophies, scientific understandings, and spiritual connections to the land. From the vast Algonquian family stretching across the East to the sophisticated Athabaskan languages of the Southwest and the intricate Salishan tongues of the Pacific Northwest, each represented a universe of thought.

The initial tremors of decline began with the earliest European incursions. The introduction of novel diseases like smallpox and measles, against which Native populations had no immunity, led to unprecedented demographic collapse. Entire communities were decimated, and with them, the delicate intergenerational transmission of language was fractured. Violence and warfare further destabilized societies, forcing displacement and disrupting the social structures essential for language maintenance. As European settlers expanded, driven by concepts of manifest destiny and land acquisition, Native peoples were pushed onto ever-shrinking reservations, severing their ties to ancestral lands that often held deep linguistic significance, encoded in place names, stories, and ceremonies.

However, the most devastating blows to Native American languages came not merely from incidental contact or disease, but from deliberate, systematic policies of forced assimilation orchestrated by the United States and Canadian governments. The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed a concerted effort to "civilize" Indigenous peoples, which often translated to eradicating their cultures, religions, and, critically, their languages.

Central to this assimilationist agenda were the notorious Indian boarding schools in the United States and residential schools in Canada. Beginning in the late 19th century, tens of thousands of Native children were forcibly removed from their families and communities and sent to these institutions, often hundreds of miles away. The stated goal, chillingly articulated by Captain Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, was to "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." At these schools, children were stripped of their traditional clothing, had their hair cut, and were forbidden to speak their native languages. Violations were met with severe corporal punishment, including beatings, solitary confinement, and even washing mouths out with lye soap.

The psychological and emotional trauma inflicted by these schools was immense and long-lasting. Children who spoke their language were taught to associate it with pain, shame, and punishment. When they returned to their communities, many were alienated from their elders, unable to communicate in their ancestral tongues, and often reluctant to teach their own children, fearing they would face similar suffering or be disadvantaged in the dominant English-speaking society. This broke the vital chain of intergenerational transmission, arguably the single most catastrophic factor in the decline of Native American languages. The trauma reverberates to this day, contributing to what is now understood as intergenerational historical trauma, impacting mental health and cultural continuity.

Beyond the boarding schools, other government policies further eroded linguistic vitality. The Dawes Act of 1887 (General Allotment Act) broke up communal tribal lands into individual plots, often selling off "surplus" land to non-Native settlers. This policy undermined tribal sovereignty and community cohesion, vital for language maintenance. Later, the "Termination Policy" of the 1950s aimed to end federal recognition of tribes and assimilate Native Americans fully into mainstream society, often leading to the loss of reservation lands and the dissolution of tribal governments, further destabilizing linguistic communities. The "Relocation Program" encouraged Native Americans to move from reservations to urban centers, isolating individuals from their language communities and accelerating language shift to English.

Economic pressures also played a significant role. In a society dominated by English, fluency in the ancestral language was often perceived as a barrier to economic advancement, educational opportunities, and social integration. To navigate the dominant culture, secure jobs, and access services, English became a necessity. This created a powerful incentive for parents to raise their children exclusively in English, prioritizing their perceived future success over linguistic heritage. The stigma associated with speaking Native languages, often perpetuated by the dominant society, further discouraged their use in public spaces.

The consequences of this sustained assault have been devastating. Of the hundreds of languages spoken pre-contact, only an estimated 175 remain today, and fewer than 20 of these are considered "active" with robust speaker populations across all generations. The vast majority are critically endangered, with only a handful of elderly fluent speakers left. When these elders pass, entire lexicons, grammars, and ways of understanding the world vanish with them.

The loss of language is not merely the loss of words; it is the erosion of unique knowledge systems. Native languages often contain intricate vocabularies for local flora, fauna, and ecological processes, reflecting millennia of sustainable interaction with specific environments. They embody distinct concepts of time, space, and human relationship to the natural world. For example, some Native American languages distinguish between animate and inanimate objects in ways that reflect a profound spiritual connection to all living things, a concept often lost in English translation. The Hopi language, for instance, has a unique temporal system that doesn’t simply categorize events into past, present, and future but emphasizes the duration and nature of events, influencing their worldview.

Moreover, language is inextricably linked to identity and sovereignty. For many Indigenous peoples, their language is a direct connection to their ancestors, their spiritual practices, and their very sense of self. The celebrated Navajo Code Talkers of World War II serve as a poignant, albeit ironic, example of the hidden power and strategic value of Native languages. Their unbreakable code, based on the Navajo language, was instrumental in Allied victories, demonstrating the profound utility and complexity of a language that had been systematically suppressed just decades prior.

In recent decades, there has been a powerful resurgence of Indigenous language revitalization efforts across North America. Communities are working tirelessly to reclaim and restore their ancestral tongues through immersion schools, master-apprentice programs, language camps, and digital resources. These efforts, though often underfunded and facing immense challenges, represent a profound act of cultural resilience and self-determination.

However, the legacy of historical policies continues to cast a long shadow. The causes of the decline of Native American languages are not abstract historical events; they are the direct result of deliberate actions and systemic pressures that have profoundly reshaped Indigenous societies. Understanding this history is not just an academic exercise; it is a crucial step towards acknowledging the profound injustices committed, supporting ongoing revitalization efforts, and recognizing the invaluable contribution that Indigenous languages represent to the rich tapestry of human diversity. The echoes of silence remind us of what has been lost, and the urgent imperative to preserve the voices that remain.