Echoes of Resilience: The Enduring Spirit of Warm Springs

In the rugged, sun-drenched expanse of Central Oregon, where the high desert meets the verdant canyons carved by ancient rivers, lies a territory that is more than just a dot on a map. The Warm Springs Indian Reservation, home to the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs (CTWS), is a living testament to an enduring spirit, a place where deep cultural roots intertwine with the complex challenges and unwavering hopes of modern Native American self-determination. It is a land shaped by fire and ice, by the mighty Deschutes and Metolius rivers, and, most profoundly, by the stories and resilience of its people.

Spanning approximately 640,000 acres, or just over 1,000 square miles, the Warm Springs Reservation is a land of striking contrasts. Sagebrush flats give way to ponderosa pine forests, while dramatic river gorges conceal ancient pictographs and sacred fishing grounds. This diverse landscape has been home to the ancestors of the three distinct tribes that now form the CTWS: the Warm Springs Sahaptin, the Wasco (Kiksht speakers), and the Northern Paiute. Each brought their unique language, customs, and histories, but were brought together by circumstance and the shared necessity of survival and self-governance.

The story of the Confederated Tribes officially begins with the Treaty of 1855, a pivotal and often painful moment in their history. In exchange for ceding millions of acres of their ancestral lands, which stretched across much of present-day Oregon and Washington, the tribes reserved a smaller tract for their exclusive use and maintained crucial rights to hunt, fish, and gather traditional foods on their "usual and accustomed places" off the reservation. This treaty, like many others of its era, was a stark reduction of their domain, but it also laid the foundation for their continued existence as a sovereign nation. The Paiutes, displaced from their traditional homelands to the south, were later welcomed into the confederation in 1879, further enriching the cultural tapestry of Warm Springs.

Life on the reservation has always been a delicate balance between tradition and adaptation. For generations, the rivers – particularly the Columbia and its tributaries like the Deschutes – were the lifeblood, providing abundant salmon that sustained physical and spiritual well-being. The annual First Salmon Ceremony remains a powerful reminder of this sacred connection to the land and its resources. Gathering traditional roots, berries, and hunting deer and elk continue to be vital cultural practices, reinforcing the deep reverence for the natural world that permeates tribal identity.

"Our land is our first teacher," explains a tribal elder, her voice resonant with the wisdom of generations. "It tells us who we are, where we come from. When we listen, it guides us." This profound connection is evident in ongoing efforts to revitalize native languages – Kiksht (Wasco), Ichishkíin (Warm Springs Sahaptin), and Numu (Paiute). Language immersion programs and cultural centers are vibrant hubs, ensuring that the ancient tongues, once threatened by assimilation policies, continue to echo through the next generation, preserving stories, songs, and ways of understanding the world unique to each tribe.

Economically, Warm Springs has navigated a challenging path. For much of the 20th century, timber resources formed the backbone of the tribal economy. The vast forests provided jobs and revenue, allowing the tribes to invest in schools, healthcare, and infrastructure. However, like many timber-dependent communities, Warm Springs faced significant economic disruption as the industry declined in the late 20th century due to environmental concerns, market shifts, and reduced harvest levels.

In the late 1980s, the tribes embarked on a new economic venture, one that symbolized both hope and a pragmatic embrace of modern enterprise: gaming. The Kah-Nee-Ta High Desert Resort & Casino, built amidst the stunning natural beauty of the reservation, became a regional attraction, offering hot springs, a lodge, a village, and a casino. For decades, it was a significant employer and revenue generator, funding tribal government services and initiatives. However, increased competition from other casinos and the resort’s remote location eventually led to its closure in 2018, a devastating blow to the tribal economy and the community’s morale.

The closure of Kah-Nee-Ta underscored the inherent vulnerability of relying on a single industry. In its wake, the Confederated Tribes have redoubled efforts to diversify their economic portfolio. Energy generation has emerged as a key area. The tribes own and operate a portion of the Pelton Round Butte Hydroelectric Project on the Deschutes River, a significant source of clean energy and revenue. There are also ongoing explorations into solar and other renewable energy projects, aligning economic development with environmental stewardship. Natural resource management, including sustainable forestry and fisheries enhancement, remains a vital sector.

"Sovereignty isn’t just a word; it’s the daily work of building a future for our people," states a tribal council member. "It means making tough decisions, learning from setbacks, and always pushing forward for self-sufficiency and the well-being of our community." The tribal government, operating with the authority of a sovereign nation, oversees a wide array of services including police, fire, education, healthcare, social services, and infrastructure maintenance, all funded through a mix of tribal enterprises, federal grants, and state partnerships.

Despite these efforts, significant challenges persist. Unemployment rates on the reservation often remain higher than the state average, and poverty continues to impact many families. Infrastructure, particularly housing and water systems, requires substantial investment. The effects of historical trauma – the intergenerational impact of forced assimilation, land dispossession, and cultural suppression – manifest in social and health disparities. Access to quality healthcare and educational opportunities, while improving, remains an ongoing priority.

One of the most pressing concerns for Warm Springs, particularly in an era of climate change, is water. The reservation’s aging water infrastructure has led to a series of boil water notices in recent years, highlighting the urgent need for modernization. The tribes are actively pursuing solutions, including federal funding and partnerships, to ensure reliable access to clean, safe drinking water for all residents. Water rights, intricately tied to the 1855 Treaty, are also a perpetual focus, crucial for both human consumption and the health of the ecosystem.

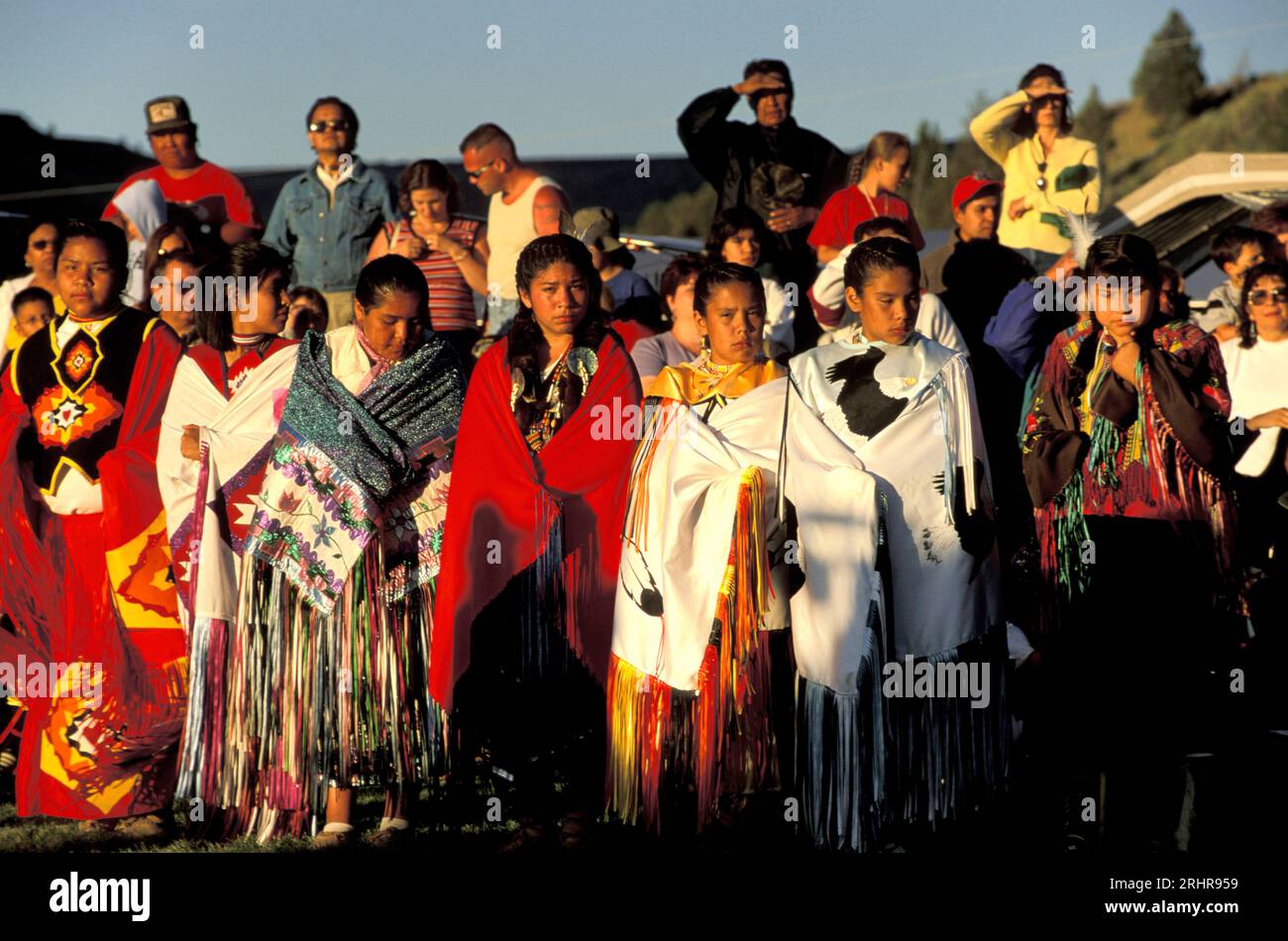

Yet, amidst these difficulties, the spirit of Warm Springs remains undiminished. It is a community characterized by an extraordinary sense of collective identity and purpose. Tribal members volunteer their time for cultural events, youth programs, and environmental restoration projects. The annual Pi-Ume-Sha Treaty Days Celebration, a vibrant powwow and rodeo, draws thousands, showcasing traditional dances, drumming, and horsemanship – a powerful affirmation of their living culture.

The future of Warm Springs is being shaped by its younger generations, who are embracing both their heritage and the opportunities of the modern world. Many leave the reservation for higher education or specialized training, but a significant number return, bringing new skills and perspectives to serve their community. They are the inheritors of a profound legacy, tasked with balancing progress with preservation, innovation with tradition.

The Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs are not merely surviving; they are actively thriving on their own terms. Their journey is a complex tapestry woven with threads of hardship and resilience, loss and reclamation. From the ancient salmon runs to the aspirations of new economic ventures, from the echoes of ancestral languages to the modern challenges of infrastructure and climate change, Warm Springs stands as a powerful symbol of Indigenous self-determination in America. It is a place where the past informs the present, and where an unwavering commitment to land, culture, and community continues to forge a vibrant and hopeful future.