Beyond the Myth: The Enduring Legacy of the Wampanoag and New England’s Complex Heritage

Every November, across the United States, families gather to celebrate Thanksgiving, a holiday steeped in imagery of Pilgrims, Native Americans, and a shared harvest feast. This iconic tableau, often romanticized and simplified, tells only a fraction of a far more intricate and profound story—a story that begins with the Wampanoag Nation, the true hosts of the "First Thanksgiving," and continues through centuries of alliance, conflict, resilience, and an ongoing struggle for recognition and sovereignty. To understand New England’s true heritage is to journey beyond the myth and confront the complex, often painful, yet ultimately triumphant legacy of the Wampanoag people.

For millennia before European contact, the Wampanoag, meaning "People of the First Light," thrived across southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island, including Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. Their sophisticated society, estimated to number between 50,000 and 100,000 individuals across 69 villages, was deeply connected to the land and sea. They were expert farmers, cultivating corn, beans, and squash (the "Three Sisters"), skilled fishermen, and adept hunters. Their governance was a confederation of tribes, each led by a sachem, bound by intricate social, political, and economic networks. Their spiritual beliefs were interwoven with the natural world, fostering a sustainable relationship with their environment.

The arrival of European fishing and trading vessels in the early 17th century heralded an unprecedented catastrophe. Between 1616 and 1619, a devastating epidemic, likely leptospirosis, smallpox, or another European disease, swept through the Wampanoag communities, wiping out an estimated 75-90% of their population. Villages were decimated, ancestral knowledge lost, and the social fabric severely strained. It was into this ravaged landscape that the English Separatists, known as Pilgrims, stumbled ashore in Patuxet (renamed Plymouth by the English) in 1620. They found a cleared village, fertile fields, and an abundance of abandoned resources—a testament to the recent devastation.

The Pilgrims, ill-prepared for the harsh New England winter, suffered immense losses, with half their number perishing within months. Their survival hinged on the assistance of the Wampanoag. In March 1621, a pivotal moment occurred: Samoset, an Abenaki sagamore who spoke some English, introduced the Pilgrims to Tisquantum, or Squanto, a Pawtuxet Wampanoag who had been kidnapped by English explorers, taken to Europe, and eventually returned home to find his entire village wiped out by the plague. Squanto became an indispensable interpreter, cultural liaison, and teacher, instructing the Pilgrims on how to cultivate native crops, identify edible plants, and fish for eels.

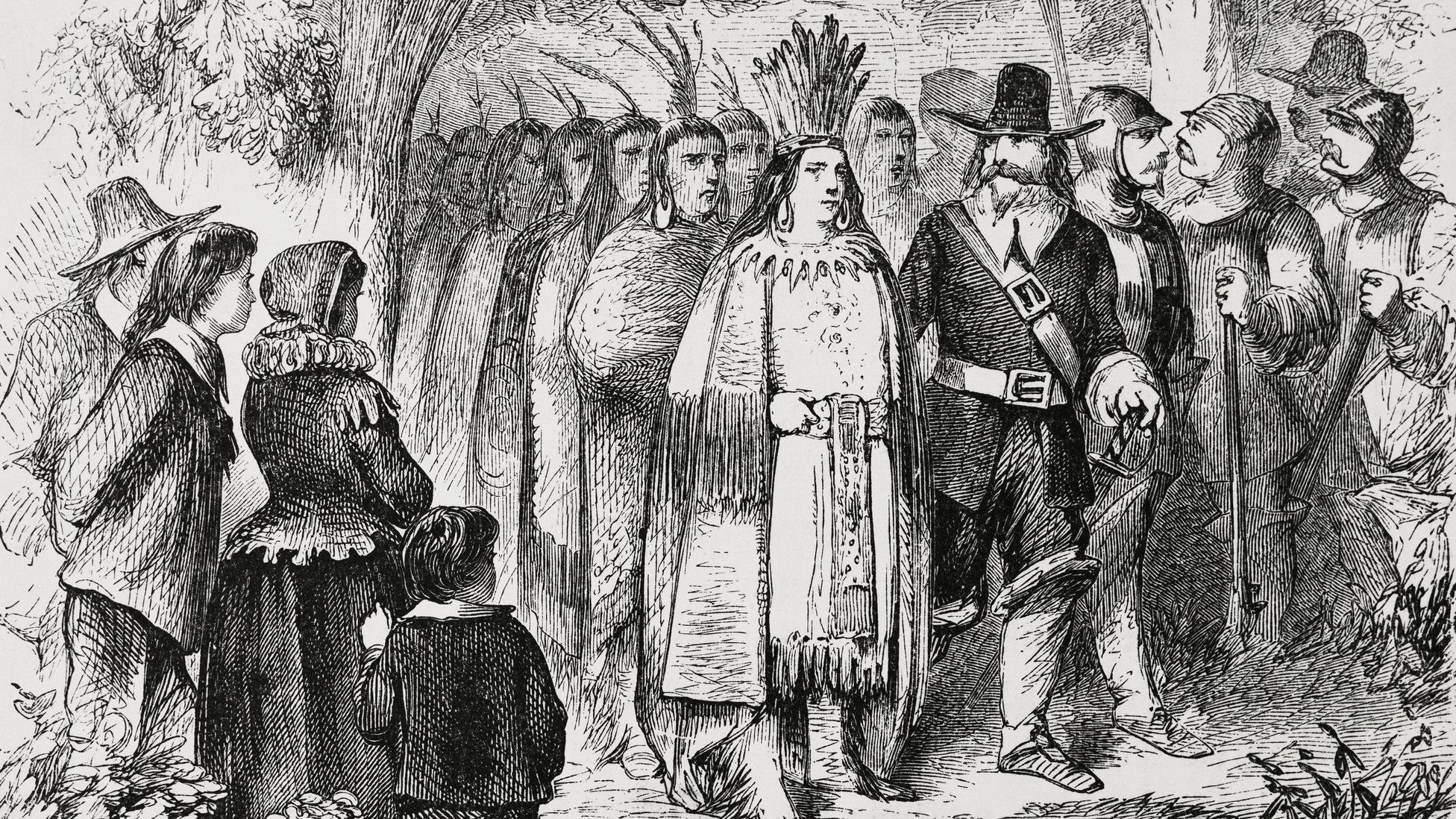

Crucially, Squanto also facilitated a historic treaty between the Pilgrims and Ousamequin Massasoit, the sachem of the Pokanoket Wampanoag, the most powerful Wampanoag leader in the region. Massasoit, acutely aware of his tribe’s weakened state following the epidemic and facing threats from rival tribes like the Narragansett, saw a strategic advantage in an alliance with the English. The treaty, a pact of mutual defense and non-aggression, was a calculated political move for both sides, born out of necessity rather than simple camaraderie.

The "First Thanksgiving" of 1621, a three-day harvest feast, was a direct consequence of this alliance. While the Pilgrims celebrated their first successful harvest, Massasoit arrived with approximately 90 Wampanoag men, likely responding to the Pilgrims’ celebratory gunfire, which they mistook for a hostile attack. Upon realizing it was a feast, the Wampanoag contributed five deer, showcasing their hospitality and reinforcing the diplomatic relationship. This was not a "Thanksgiving" in the modern sense, but a traditional European harvest festival combined with a crucial diplomatic gathering, a testament to a fragile, mutually beneficial peace.

However, this peace was short-lived. The trickle of English settlers soon became a flood. Their insatiable demand for land, driven by agricultural expansion and a different concept of land ownership (individual property vs. communal stewardship), quickly eroded the Wampanoag’s ancestral territories. The English also brought new diseases, legal systems that undermined Wampanoag sovereignty, and attempts at forced religious conversion through "praying towns." The power dynamic shifted dramatically, with the Wampanoag increasingly marginalized and dispossessed.

This escalating tension culminated in King Philip’s War (1675-1678), one of the deadliest conflicts in American history relative to population. Metacom, Massasoit’s son, known to the English as King Philip, inherited his father’s sachemship and witnessed the systematic erosion of his people’s way of life. Recognizing the existential threat, he forged a confederation of Native tribes to resist colonial expansion. The war was brutal, characterized by devastating raids, massacres, and immense suffering on all sides. By its end, Metacom was killed, and the Wampanoag, along with many other Native nations in Southern New England, were decimated. Many survivors were sold into slavery in the Caribbean, while others fled, were forced into indentured servitude, or assimilated into "praying towns" to survive.

Despite these immense losses and centuries of oppression, the Wampanoag Nation never vanished. They endured, often in hidden communities, maintaining their cultural identity through intermarriage, adaptation, and fierce determination. Their story became one of incredible resilience and cultural continuity, passed down through generations.

Today, the Wampanoag Nation endures through federally recognized tribes like the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), as well as state-recognized and historical bands. These communities are experiencing a vibrant cultural renaissance. They are actively engaged in reclaiming their ancestral lands, revitalizing their language (Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project), preserving traditional arts and crafts, and educating the public about their true history. "We are still here," is a powerful declaration often heard from Wampanoag people, underscoring their unbroken connection to their past and their future.

The Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, for instance, is a monumental effort to bring back a language that had no native speakers for over 150 years. Jessie Little Doe Baird, a Mashpee Wampanoag tribal member, pioneered this effort, earning a MacArthur "genius grant" for her work. Through painstaking research of historical documents and collaboration with linguists, the language is now being taught to children and adults, a profound act of cultural healing and self-determination.

The contemporary Wampanoag also confront the challenges of modern life, including economic development, healthcare, and the ongoing struggle for full recognition of their sovereignty. The Mashpee Wampanoag, after a decades-long battle, had their reservation land officially recognized by the federal government, a crucial step in self-governance, though it continues to face legal challenges. This fight for land and self-determination is a direct continuation of the struggles that began with the arrival of the Pilgrims.

New England’s heritage, therefore, is not solely defined by Puritan piety, colonial expansion, or revolutionary fervor. It is also, profoundly and inextricably, shaped by the Wampanoag Nation. Museums, educational institutions, and public discourse in the region are increasingly re-evaluating historical narratives, acknowledging the Wampanoag perspective, and moving towards a more inclusive understanding of the past. Plymouth’s annual "National Day of Mourning," observed by Native Americans since 1970 on the same day as Thanksgiving, serves as a powerful reminder of the genocide and dispossession that followed the initial alliance.

The story of the Wampanoag is more than a quaint historical footnote; it is a testament to the endurance of a people, a living narrative that challenges prevailing myths and demands a more nuanced understanding of America’s origins. It is a call to confront the full spectrum of New England’s heritage—its moments of shared humanity, its profound injustices, and the indomitable spirit of its first peoples who continue to rise, reminding us all that their light, the first light, still shines brightly. By embracing this richer, more truthful history, we can foster a deeper appreciation for the complex tapestry of cultures that truly define New England and the nation as a whole.