Understanding Native American Tribal Sovereignty: Legal Rights and Modern Challenges

Native American tribal sovereignty is a concept as fundamental as it is frequently misunderstood. It represents the inherent right of Indigenous nations to govern themselves, a right that predates the formation of the United States and continues to shape the complex legal and political landscape of North America. Far from a concession granted by the federal government, tribal sovereignty is an inherent authority, recognized through treaties and affirmed by centuries of legal precedent, yet perpetually challenged by historical injustices and contemporary pressures. This article delves into the bedrock of these legal rights and examines the pressing challenges tribes face in asserting their self-determination today.

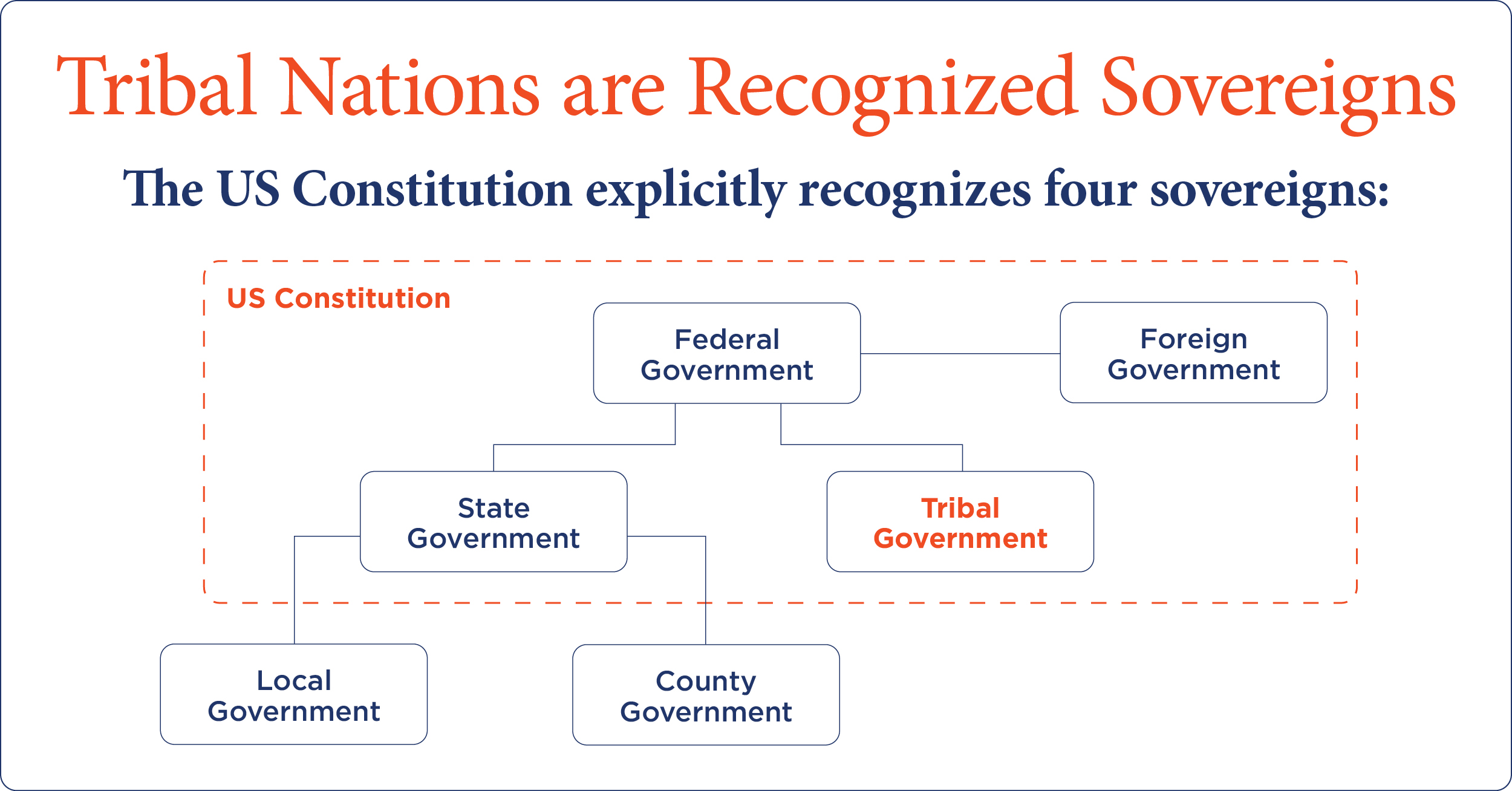

At its core, tribal sovereignty means that Native American tribes possess the power to make and enforce their own laws, to govern their lands, and to determine their own membership and forms of government. It is a nation-to-nation relationship, implying that tribes are not merely subdivisions of states or the federal government, but distinct political entities. This concept, however, has been consistently eroded, reinterpreted, and fought for since European contact.

Historical Roots and Legal Precedent: A Nation-to-Nation Relationship

Before the arrival of European colonists, hundreds of diverse Indigenous nations thrived across the continent, each with its own sophisticated governance systems, laws, and territories. Their sovereignty was absolute and undisputed. The early interactions between these nations and European powers, and later the nascent United States, often took the form of treaties – solemn, legally binding agreements between sovereign entities. These treaties, some of which are still in force today, cemented the understanding of a nation-to-nation relationship, recognizing tribal land rights and the right to self-governance. Article VI of the U.S. Constitution, which declares treaties the "supreme Law of the Land," theoretically enshrines these agreements.

However, as the United States expanded, its policies shifted from treaty-making to land acquisition, assimilation, and outright subjugation. Despite this, the U.S. Supreme Court delivered foundational rulings in the early 19th century that, while limiting tribal power, unequivocally affirmed their sovereign status. The "Marshall Trilogy" – a series of cases decided by Chief Justice John Marshall – laid the legal groundwork:

- Johnson v. M’Intosh (1823): This case established the "discovery doctrine," asserting that European nations gained ultimate title to discovered lands, but Native American tribes retained the right of occupancy. This significantly curtailed tribal land rights but acknowledged their continued presence.

- Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831): Here, Marshall famously described tribes as "domestic dependent nations," meaning they were sovereign but subject to the paramount authority of the United States, particularly Congress. They were not foreign states but distinct political communities.

- **Worcester v. Georgia (1832):** In a landmark decision, the Court ruled that Georgia state law had no force within Cherokee territory, affirming tribal sovereignty against state infringement. Marshall stated that the Cherokee Nation was a "distinct community, occupying its own territory, with boundaries accurately described, in which the laws of Georgia can have no force."

These rulings, while paradoxical in their simultaneous recognition and limitation of tribal power, established that tribal sovereignty is inherent and not granted by the federal government. It is a pre-existing right.

The subsequent history of federal Indian policy swung wildly between recognizing and attempting to extinguish tribal sovereignty. The Allotment Era (1887-1934), ushered in by the Dawes Act, aimed to break up tribal landholdings and assimilate Native Americans into mainstream society. The Termination Era (1953-1968) went even further, attempting to abolish federal recognition of tribes and their sovereign status altogether. Both policies were catastrophic failures, leading to immense poverty, land loss, and social dislocation.

The tide began to turn with the Self-Determination Era, initiated in the 1970s. This period saw a renewed federal commitment to supporting tribal self-governance, exemplified by the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This act allowed tribes to contract directly with the federal government to administer programs previously run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, marking a significant step towards restoring tribal control over their own affairs.

Pillars of Modern Tribal Governance and Rights

Today, tribal sovereignty manifests in various critical domains:

- Jurisdiction: Tribes have the authority to establish their own courts and enforce laws within their reservation boundaries. This includes criminal and civil jurisdiction over tribal members and, in many cases, over non-members for civil matters arising on tribal land. However, a significant limitation was imposed by Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe (1978), which ruled that tribes, by virtue of their "domestic dependent" status, do not possess inherent criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians for crimes committed on tribal lands. This created a dangerous jurisdictional void, often leaving victims, particularly Native women, vulnerable to crimes committed by non-Natives with impunity. Congress has since taken steps to address this, notably through amendments to the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) in 2013 and 2022, which restored some tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians in specific domestic violence, dating violence, and sexual assault cases.

- Economic Development: Tribes can engage in a wide range of economic activities, from operating casinos (regulated by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988) to developing energy resources, tourism, and manufacturing. This economic self-sufficiency is vital for funding essential tribal services and improving quality of life.

- Taxation: Tribes have the authority to levy taxes on reservation lands, including sales taxes, property taxes, and business taxes. This is a powerful tool for generating revenue and asserting governmental authority.

- Cultural Preservation: Sovereignty allows tribes to protect and promote their languages, traditions, and sacred sites. Laws like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) mandate the return of human remains and cultural items to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated tribes. The Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) aims to keep Native American children within their families and communities, recognizing the unique cultural context of tribal families.

- Resource Management: Tribes manage vast natural resources on their lands, including forests, water, minerals, and wildlife, often exercising environmental regulatory authority.

- Healthcare and Education: Tribes can operate their own healthcare facilities and educational institutions, tailoring services to meet the specific needs and cultural values of their communities.

Modern Challenges: The Enduring Struggle for Self-Determination

Despite the legal affirmations and progress in self-determination, tribal sovereignty faces significant and persistent challenges:

- Jurisdictional Complexities and Gaps: The Oliphant ruling continues to plague tribal justice systems, creating a patchwork of jurisdiction that can be exploited by criminals. The lack of inherent criminal jurisdiction over non-Natives means that serious crimes committed on reservations often go unprosecuted or are handled by under-resourced federal or state authorities, contributing to alarmingly high rates of violence against Native women.

- Federal Plenary Power: While tribes are sovereign, Congress retains "plenary power" over Indian affairs, meaning it can unilaterally modify or even abrogate treaties and tribal rights. This power, though ideally exercised as a trust responsibility, represents a constant threat to tribal self-governance, leaving tribes vulnerable to shifts in federal policy and political whims.

- Funding Shortfalls and Underinvestment: The federal government has a trust responsibility to Native American tribes, stemming from treaties and the unique relationship. However, federal funding for critical services like healthcare, education, housing, and infrastructure in Indian Country is chronically inadequate, often falling far short of actual needs. This forces tribes to do more with less, hindering development and well-being.

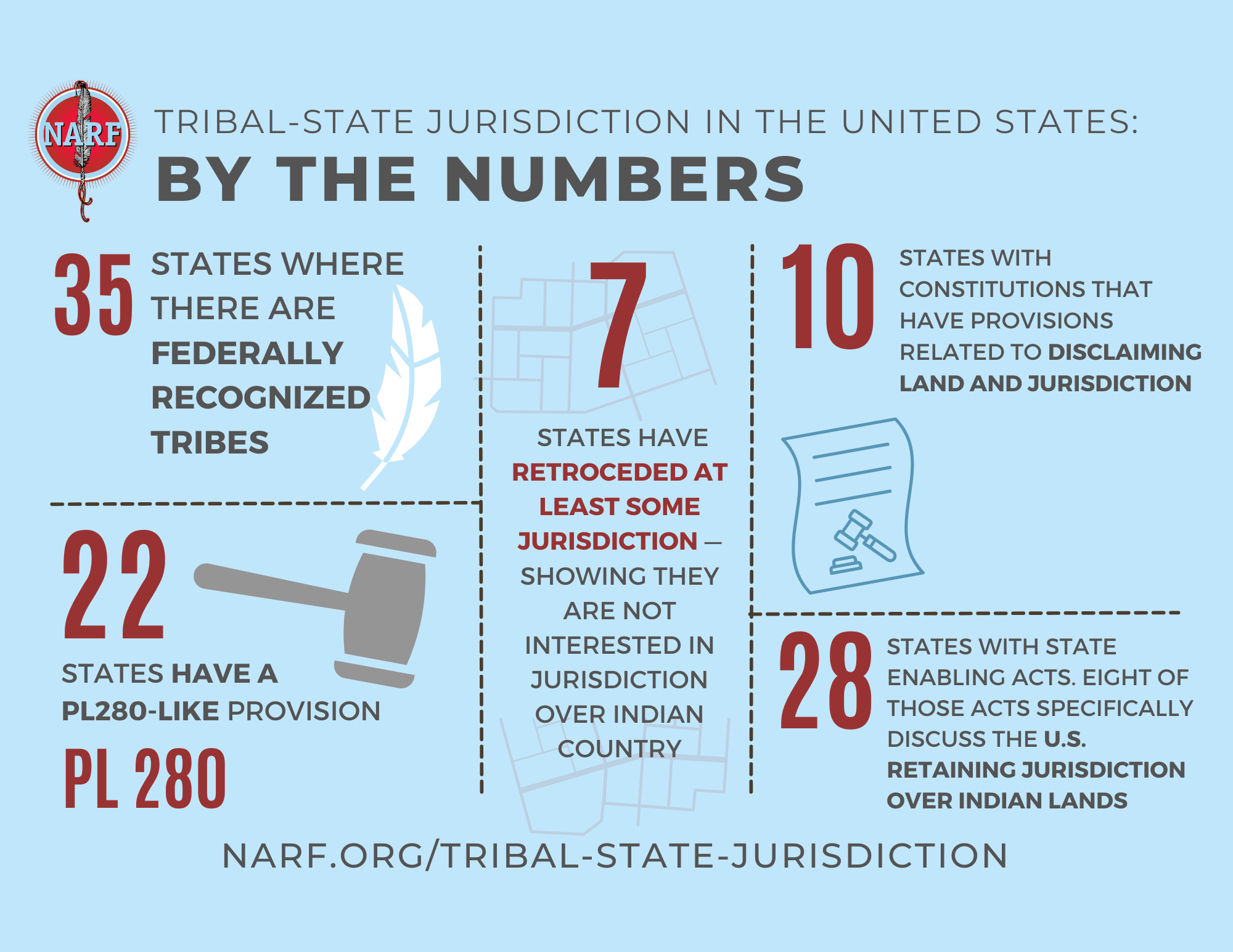

- State Interference and Resistance: Despite Worcester v. Georgia, states often attempt to assert jurisdiction or influence over tribal affairs, particularly concerning taxation, gaming, and resource management. These conflicts frequently end up in protracted and expensive legal battles.

- Economic Disparities and Resource Exploitation: While gaming has brought economic benefits to some tribes, many still face severe poverty and unemployment. Tribes often sit on valuable natural resources, leading to conflicts with external corporations and governments over extraction rights and environmental protection. The Dakota Access Pipeline protests by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe highlighted the ongoing struggle to protect tribal lands and water from external development.

- Cultural Erosion and Language Loss: Centuries of forced assimilation policies have taken a heavy toll on Indigenous languages and cultural practices. While revitalization efforts are underway, the loss of elders and fluent speakers poses an existential threat to unique cultural heritage.

- Lack of Public Understanding: A widespread lack of public awareness and understanding about tribal sovereignty perpetuates stereotypes and hinders support for tribal rights. Many Americans remain unaware of the distinct governmental status of tribes and the historical context of their relationship with the U.S.

However, recent legal victories offer glimmers of hope. In McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020), the Supreme Court ruled that a large portion of eastern Oklahoma, including most of Tulsa, remains an Indian reservation for purposes of the Major Crimes Act. This landmark decision affirmed the continuing existence of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s reservation boundaries, reasserting tribal jurisdiction and significantly impacting criminal justice in the state. The ruling has since been extended to other "Five Civilized Tribes" in Oklahoma, underscoring the enduring power of historical treaties and the imperative to uphold tribal sovereignty.

Conclusion: The Enduring Imperative of Self-Determination

Understanding Native American tribal sovereignty is not merely an academic exercise; it is crucial for upholding justice, respecting treaty obligations, and fostering healthy nation-to-nation relationships. It is a testament to the resilience of Indigenous peoples who, despite centuries of systemic oppression, have steadfastly maintained their identity and their right to self-governance.

The journey of tribal sovereignty is far from over. It is an ongoing struggle for recognition, respect, and the fulfillment of promises made. For the United States, fully embracing and supporting tribal sovereignty means more than just acknowledging legal rights; it means actively working to rectify historical wrongs, investing equitably in tribal communities, and empowering Indigenous nations to shape their own futures. Only then can the principles of self-determination truly flourish, ensuring a more just and equitable future for all.