UNDRIP on Turtle Island: From Aspiration to Implementation’s Rocky Edge

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), adopted by the General Assembly in 2007, stands as a landmark international instrument affirming the collective and individual rights of Indigenous peoples worldwide. For the diverse Indigenous nations of Turtle Island – encompassing what are now known as Canada and the United States – UNDRIP represents a powerful, long-overdue framework to rectify centuries of colonization, dispossession, and systemic discrimination. Yet, more than a decade and a half after its adoption, the journey from UNDRIP’s aspirational principles to tangible, equitable implementation remains fraught with legal complexities, political resistance, and deep-seated historical grievances.

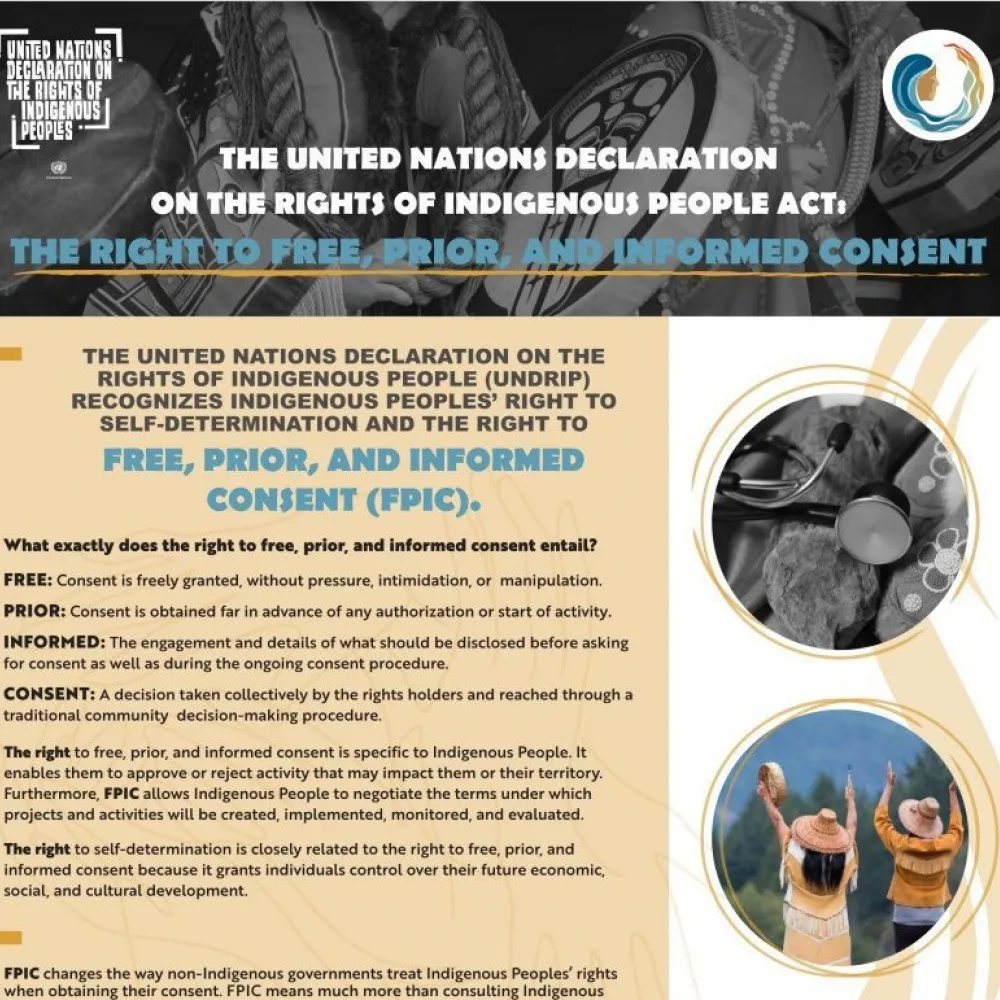

UNDRIP itself is a comprehensive declaration, outlining rights related to self-determination, land, territories and resources, culture, language, identity, health, education, and employment. Its 46 articles serve as a "minimum standard for the survival, dignity and well-being of the Indigenous peoples of the world." Crucially, it emphasizes the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) – meaning Indigenous peoples have the right to give or withhold consent for projects affecting their lands or territories, a principle that directly challenges conventional resource development and land management practices.

Initially, both Canada and the United States were among the four nations (alongside Australia and New Zealand) to vote against UNDRIP, citing concerns over its impact on national sovereignty and existing legal frameworks. This early opposition underscored a deep-seated reluctance to acknowledge the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples as distinct from those of other citizens. However, under pressure from Indigenous advocacy groups and evolving domestic political landscapes, both countries eventually reversed their positions, endorsing the Declaration – Canada in 2010 and the U.S. in 2010 (with caveats). This shift marked a significant symbolic victory, but the real work of implementation has proven to be an arduous and often contentious process.

Canada’s Path: Legislation and Its Limits

Canada has arguably taken the most direct legislative step towards implementing UNDRIP. In June 2021, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (Bill C-15) received Royal Assent, becoming federal law. This Act legally obligates the Government of Canada to "take all measures necessary to ensure that the laws of Canada are consistent with the Declaration" and to develop an action plan in consultation and cooperation with Indigenous peoples.

On paper, Bill C-15 is a transformative piece of legislation. It formally enshrines UNDRIP as a universal human rights instrument in Canadian law, creating a legal imperative for government actions to align with its principles. However, the path from legislative intent to on-the-ground reality has been anything but smooth. Critics, including many Indigenous leaders, point out that the Act itself does not automatically change existing laws or halt contentious projects. The "action plan" is still under development, and the devil, as always, is in the details of interpretation and enforcement.

The most contentious point of interpretation revolves around FPIC. While UNDRIP Article 19 states that "States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the Indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them," Canada’s federal government has often interpreted FPIC not as a veto, but as a commitment to a robust process of consultation and accommodation. This divergence in understanding has led to ongoing conflicts, particularly in the realm of resource extraction.

The ongoing disputes surrounding the Coastal GasLink pipeline project in British Columbia provide a stark illustration. Despite federal and provincial endorsements, and agreements with some elected band councils, hereditary leaders of the Wet’suwet’en Nation have consistently asserted that FPIC was not obtained for the pipeline crossing their unceded traditional territories. The ensuing blockades, protests, and police interventions highlight the chasm between Canada’s legal commitment to UNDRIP and the practical application of Indigenous sovereignty and land rights. Similarly, the long-standing mercury poisoning crisis at Grassy Narrows First Nation in Ontario, exacerbated by historical industrial logging and governmental inaction, underscores the persistent failure to protect Indigenous health and environment, despite UNDRIP’s articles on well-being and land stewardship.

The concept of "reconciliation" has become central to Canadian discourse on Indigenous relations, and Bill C-15 is framed as a key step in this process. However, for many Indigenous peoples, true reconciliation cannot occur without a fundamental shift in power dynamics, genuine respect for treaty obligations, and the full implementation of UNDRIP’s principles, including the right to self-determination over their lands and resources.

The United States: Endorsement Without Legislation

In contrast to Canada’s legislative approach, the United States has not enacted a specific federal law to implement UNDRIP. When the U.S. endorsed the Declaration in 2010, it did so with caveats, emphasizing that the Declaration "does not require changes to U.S. law" and is "non-legally binding." Instead, the U.S. government views UNDRIP as an aspirational document, consistent with its existing legal and policy framework for Native American tribes, which includes treaty obligations, the federal trust responsibility, and the recognition of tribal self-governance.

This approach means that implementation in the U.S. relies heavily on existing mechanisms, which are often inadequate or inconsistently applied. While the U.S. acknowledges tribal sovereignty and government-to-government relations, the practical extent of this sovereignty is frequently challenged by federal and state jurisdictions, particularly concerning land and resource management.

The struggles over the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) in North Dakota exemplified the limitations of the U.S. approach. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, whose treaty lands and water sources were threatened by the pipeline, invoked their inherent rights and the spirit of UNDRIP, particularly the principle of FPIC. Despite widespread protests and international attention, the pipeline was ultimately completed and remains operational, with courts often prioritizing corporate interests and existing regulatory processes over Indigenous consent. This case highlighted that without a strong legal mandate for UNDRIP, federal agencies and courts can continue to interpret "consultation" as information sharing rather than a requirement for Indigenous consent.

Another significant example is the debate over the protection of sacred sites and ancestral lands, such as Bears Ears National Monument in Utah. While the monument’s designation and subsequent reduction under different administrations have involved extensive consultation with the inter-tribal coalition that advocated for its protection, the ultimate decision-making power has remained with the federal government. UNDRIP’s Article 26, which affirms Indigenous peoples’ right to "the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired," and Article 11, which protects cultural and spiritual practices, directly speak to these issues, yet their force in U.S. law is indirect at best.

The U.S. government maintains that its existing policies, such as executive orders on tribal consultation and the affirmation of tribal inherent jurisdiction, are sufficient to uphold the spirit of UNDRIP. However, critics argue that without explicit legislation, the Declaration’s principles remain vulnerable to political shifts and inconsistent application across different federal agencies. This leaves Indigenous nations in the U.S. often fighting on a case-by-case basis, relying on litigation, advocacy, and direct action to assert their rights, rather than having a clear, federally mandated framework for UNDRIP implementation.

Common Challenges and Gaps

Across Turtle Island, several common challenges impede the full realization of UNDRIP:

-

Interpretation of FPIC: This remains the most significant hurdle. Governments often equate "consultation" with "consent," while Indigenous peoples assert FPIC as a right to say "no." Without a clear, legally binding definition and mechanism for implementing FPIC, conflicts over resource development and land use will persist.

-

Land and Resource Rights: Despite UNDRIP’s robust articles on land, territories, and resources (Articles 25-30), the colonial legacy of dispossession continues. Many Indigenous nations on Turtle Island still do not have secure title or control over their traditional territories, which are often rich in natural resources. This fuels disputes and undermines self-determination.

-

Political Will and Shifting Priorities: The commitment to UNDRIP implementation can fluctuate with changes in government. Sustained political will, coupled with adequate funding and capacity building for Indigenous governance, is essential but often lacking.

-

Jurisdictional Complexity: The intricate web of federal, provincial/state, and Indigenous jurisdictions creates significant challenges in applying UNDRIP. Clarifying these relationships and ensuring Indigenous legal orders are recognized on par with state law is crucial.

-

Addressing Historical Injustices: UNDRIP calls for remedies for historical wrongs, including "just and fair procedures for the recognition and adjudication of their rights pertaining to their lands, territories and resources" (Article 27). This necessitates not only legal reforms but also significant investments in truth, reconciliation, and healing processes to confront the enduring impacts of residential schools, boarding schools, and other assimilative policies.

Glimmers of Hope and the Path Forward

Despite these formidable challenges, there are glimmers of progress. Increased public awareness, powerful Indigenous advocacy, and a growing body of legal precedents that affirm Indigenous rights are slowly shifting the landscape. Some Indigenous nations are successfully asserting their jurisdiction over education, child welfare, and resource management, leveraging existing legal frameworks and international instruments like UNDRIP. Co-management agreements for parks and protected areas, Indigenous-led conservation initiatives, and the resurgence of Indigenous languages and cultural practices demonstrate the resilience and self-determination of Indigenous peoples.

UNDRIP is not merely a declaration; it is a living document, a tool for advocacy, and a benchmark against which the actions of states can be measured. Its implementation on Turtle Island is not a destination but an ongoing journey that requires fundamental shifts in power, a genuine commitment to partnership, and a profound respect for Indigenous sovereignty and human rights. The ultimate success of UNDRIP will depend not just on legislative enactments, but on the political courage to translate its principles into real, transformative change, ensuring that Indigenous peoples can finally exercise their inherent rights and shape their own futures on their ancestral lands.