The Unyielding Passage: Mapping the Tuscarora’s Epic Migration from Carolina to Haudenosaunee Territory

In the brutal aftermath of the Tuscarora War (1711-1713), a profound and desperate decision faced the surviving members of the Tuscarora Nation in what is now North Carolina. Decimated by conflict, disease, and the relentless encroachment of European settlers, their ancestral lands irrevocably lost, the path to survival lay not in remaining, but in an arduous, generations-long migration north. This epic journey, a testament to resilience and the enduring spirit of a people, saw thousands of Tuscarora traverse formidable landscapes to seek refuge and a new beginning among their linguistic kin, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, in what would become known as the "Sixth Nation."

The roots of this mass exodus lie deep in the violent collision of cultures that characterized early colonial America. For millennia, the Tuscarora, an Iroquoian-speaking people, had thrived in the fertile lands of present-day eastern North Carolina. Their sophisticated agricultural practices, extensive trade networks, and well-organized towns spoke of a powerful and established civilization. However, the arrival of European settlers in the late 17th and early 18th centuries brought with it disease, land disputes, and the abhorrent practice of Indian enslavement. As colonial settlements expanded, the Tuscarora found their territory shrinking, their hunting grounds depleted, and their people subjected to kidnappings and forced labor.

Tensions escalated dramatically, culminating in the Tuscarora War. Sparked by a combination of land dispossession, enslavement, and cultural disrespect, the war saw the Tuscarora, initially allied with other Native groups, launch a series of devastating attacks on colonial settlements. The conflict was brutal, marked by sieges, massacres, and scorched-earth tactics from both sides. Ultimately, with the aid of South Carolina militias and their Native allies, the colonists inflicted a decisive defeat on the Tuscarora at Fort Neoheroka in March 1713. Hundreds of Tuscarora warriors were killed or captured, and thousands more were enslaved. The war effectively shattered the Tuscarora’s power and autonomy in the region.

"The defeat at Fort Neoheroka was more than just a military loss; it was an existential crisis for the Tuscarora," notes historian Dr. Eleanor Vance. "With their main stronghold destroyed and their population decimated, remaining in Carolina meant either subjugation, enslavement, or annihilation. The choice to migrate was born of absolute necessity, a desperate gamble for cultural and physical survival."

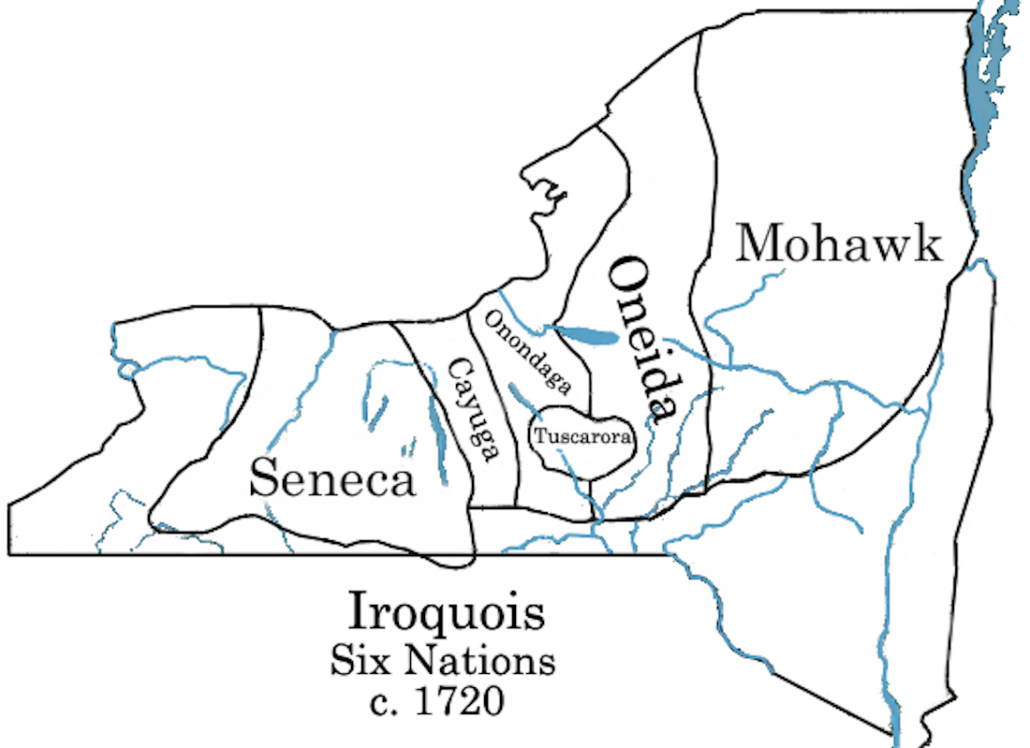

Following the war, a portion of the Tuscarora who remained in North Carolina eventually secured a small reservation, but their numbers and influence were greatly diminished. For the majority, however, the gaze turned northward, toward the distant territories of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (comprising the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca Nations) in what is now upstate New York. There, they knew, lay a possibility of kinship, protection, and the chance to rebuild.

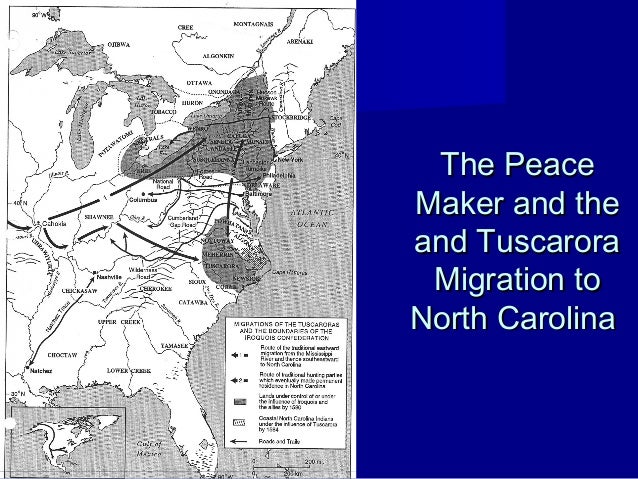

The migration was not a singular, mass movement, but rather a series of fragmented journeys, unfolding over several decades. The initial waves were often small, desperate groups of families and clans, led by experienced hunters and warriors who knew the vast, interconnected network of Native American trails that crisscrossed the eastern seaboard. These initial travelers sought immediate refuge, often pausing in Pennsylvania and parts of New York, forming temporary settlements or integrating with other Iroquoian-speaking groups.

Mapping these routes reveals a testament to ingenuity and endurance. The primary conduit for the Tuscarora was the ancient "Great Indian Warpath," a sprawling network of trails that ran parallel to the Appalachian Mountains. This path, known by various names such as the "Warriors’ Path" or "Catawba Path," stretched from the Carolinas all the way to the Great Lakes. It was a well-trodden route, carved out over millennia by trade, hunting, and inter-tribal conflict, offering a familiar, if arduous, pathway north.

From their traditional territories in eastern North Carolina, the Tuscarora would have initially moved westward, skirting the nascent colonial settlements, towards the Piedmont and then into the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. Their journey would have then generally followed the Great Valley of Virginia, a fertile corridor between the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east and the Allegheny Mountains to the west. This valley provided access to water sources, game, and relatively easier travel than the rugged peaks.

Further north, the routes would have converged towards the Susquehanna River system in Pennsylvania. The Susquehanna, a major waterway, offered both a means of travel by canoe and a guidepost for overland journeys. Tuscarora groups would have navigated its tributaries, sometimes settling for periods along its banks before continuing their northward push. "The river systems were their highways," explains Dr. Vance, "providing not just a path, but also sustenance through fishing and access to other Indigenous communities."

The journey was fraught with unimaginable peril. Traveling through dense forests, across treacherous mountain passes, and navigating swollen rivers, the Tuscarora faced starvation, disease, and exposure to the elements. They were often pursued by colonial militias or bounty hunters seeking to capture and enslave them. Furthermore, the territories they traversed were not empty; they were the homelands of other Indigenous nations, some of whom were neutral, others potentially hostile, depending on existing alliances and conflicts. Each step was a negotiation for survival, requiring diplomatic skill, resilience, and an unwavering belief in their destination.

By the 1720s, significant numbers of Tuscarora had begun to arrive in Haudenosaunee territory. Their arrival was not unexpected. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy had long maintained a policy of adopting displaced or conquered peoples, integrating them into their social and political structures, often to bolster their numbers and influence. Crucially, the Tuscarora shared a common Iroquoian linguistic and cultural heritage with the Haudenosaunee, facilitating their eventual integration.

In 1722, the Tuscarora were formally accepted into the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, becoming the Sixth Nation. This momentous event solidified their place within the powerful alliance and provided them with the protection and collective strength of the Longhouse. They were granted lands primarily by the Oneida Nation, establishing new communities and contributing their unique perspectives and traditions to the Confederacy.

"The Tuscarora brought with them not just their families, but their spirit, their stories, and their unwavering determination to remain a people," recounts an oral tradition often shared by Haudenosaunee elders. "They reminded us that our strength comes from unity, and that even in the darkest times, the path to continuity can be found."

The impact of the Tuscarora migration was profound, both for the Tuscarora themselves and for the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. For the Tuscarora, it represented an extraordinary act of self-preservation, a successful, if painful, relocation that allowed their nation to persist. They rebuilt their communities, maintained their cultural practices, and contributed significantly to the political and military strength of the Confederacy. For the Haudenosaunee, the addition of the Tuscarora further solidified their position as a dominant power in the Northeast, reinforcing the Great Law of Peace and demonstrating their capacity for inclusive governance.

Today, the legacy of the Tuscarora migration endures. Vibrant Tuscarora communities thrive in both New York (near Niagara Falls, on the Tuscarora Reservation) and Ontario, Canada (on the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve). These communities are living testaments to the incredible journey of their ancestors, continuing to uphold their language, ceremonies, and traditions. The migration routes, though now overlaid with modern infrastructure, remain etched in the collective memory, serving as a powerful reminder of a people’s unwavering commitment to sovereignty and cultural survival against overwhelming odds.

The Tuscarora’s journey from the coastal plains of Carolina to the Longhouses of the Haudenosaunee is more than a historical footnote; it is an epic narrative of displacement, endurance, and ultimately, triumph. It underscores the profound and often brutal realities of early colonial expansion, but more importantly, it celebrates the indomitable spirit of Indigenous peoples who, faced with annihilation, chose instead to walk a path of resilience, forging new alliances and ensuring the future of their nation against the tides of history. Their passage north was not just a physical movement, but a sacred journey of identity, echoing through generations and continuing to inspire.