Turtle Island vs. Pangea: Two Visions of Earth’s Foundation

The ground beneath us, solid and seemingly immutable, holds vastly different meanings depending on the lens through which it is viewed. For many Indigenous peoples of North America, this land is known as Turtle Island, a sacred entity born of ancient creation stories, a living metaphor for resilience and responsibility. For the scientific community, the continents we inhabit are fragments of a colossal ancient supercontinent, Pangea, its existence pieced together through meticulous geological detective work spanning millions of years. These two concepts—Turtle Island and Pangea—represent profoundly different epistemologies, one rooted in spiritual and cultural cosmology, the other in empirical observation and scientific theory. Yet, both offer powerful frameworks for understanding our place on Earth, inviting us to explore the depths of our planet’s history and our relationship to it.

Pangea: The Scientific Supercontinent

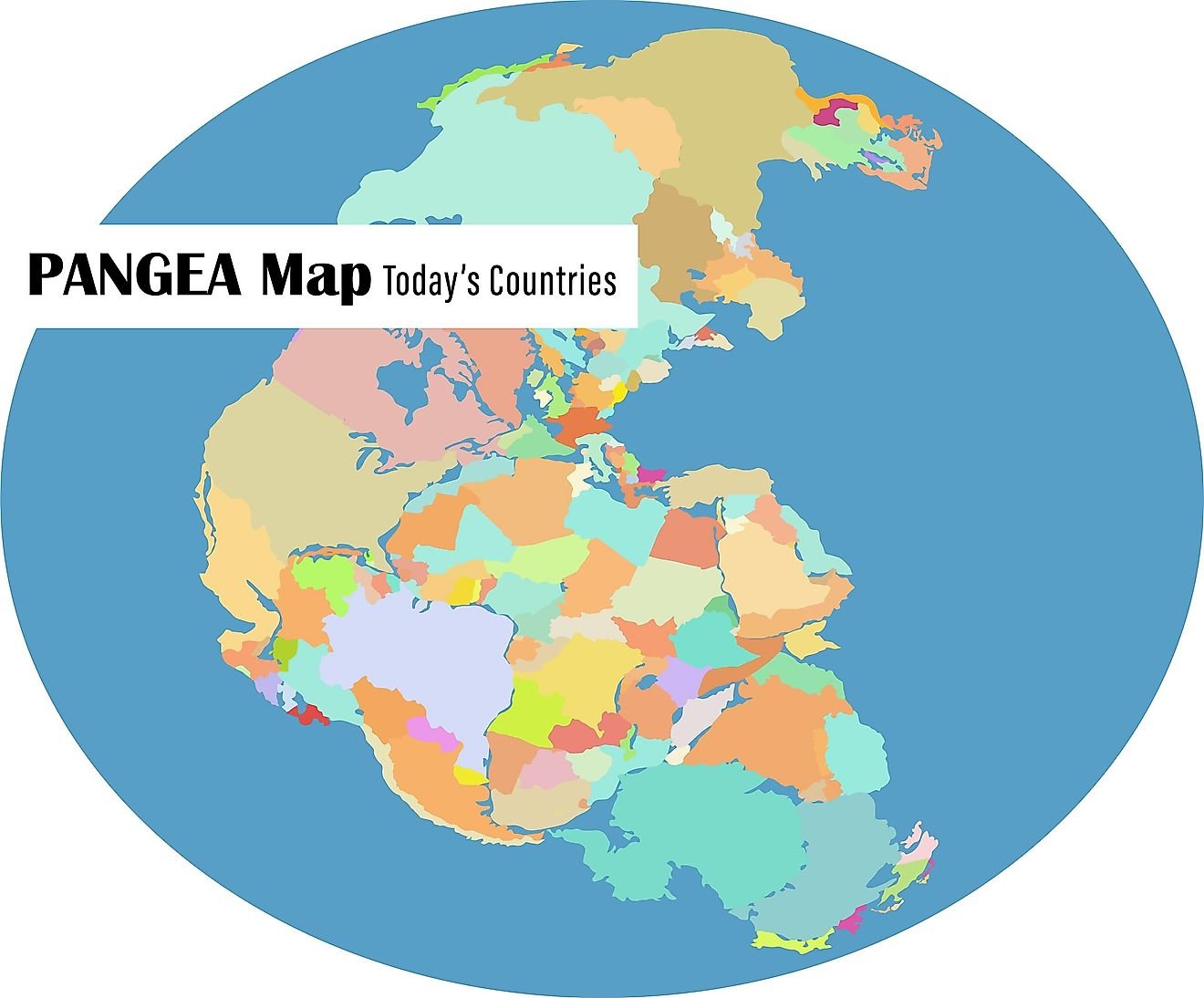

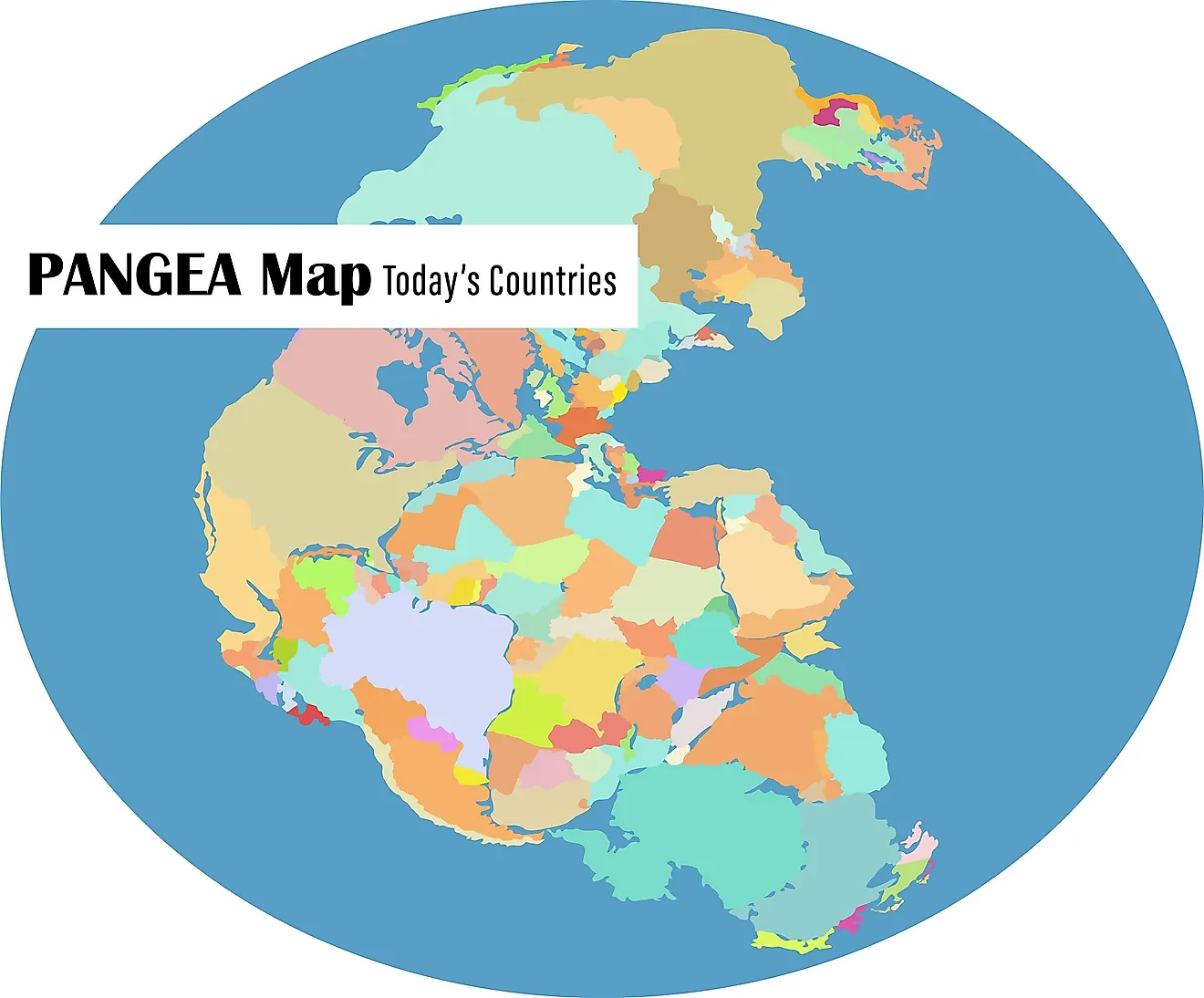

The concept of Pangea emerged from the scientific revolution of the early 20th century, spearheaded by German meteorologist Alfred Wegener. In 1912, Wegener proposed his audacious hypothesis of continental drift, suggesting that the Earth’s continents were not static but had once been joined together in a single landmass before slowly drifting apart. He named this ancient supercontinent "Pangea," meaning "all lands" in Greek.

Wegener’s initial proposal, though revolutionary, faced considerable skepticism from the scientific establishment. He lacked a convincing mechanism for how continents could "drift." However, the evidence he presented was compelling and laid the groundwork for what would become one of the most transformative theories in Earth science: plate tectonics.

Wegener’s primary lines of evidence included:

- The "Jigsaw Fit" of Continents: The remarkable visual congruence between the coastlines of continents, most notably the eastern coast of South America and the western coast of Africa, suggested they were once connected.

- Fossil Evidence: Identical fossil species of plants and animals were found on continents now separated by vast oceans. For example, the fern Glossopteris was found across South America, Africa, Antarctica, India, and Australia. The freshwater reptile Mesosaurus fossils were found only in South America and Africa. Such distribution was inexplicable without a former land bridge or continental connection.

- Rock Types and Mountain Ranges: Geologically, similar rock formations and mountain chains were observed on widely separated continents. The Appalachian Mountains in eastern North America, for instance, share geological characteristics with the Caledonian Mountains in Scotland and Scandinavia, indicating they were part of a continuous range before Pangea broke apart.

- Paleoclimate Evidence: Evidence of ancient climates, such as glacial striations (scratches left by glaciers) in regions that are now tropical (like parts of Africa and India), indicated these landmasses were once located near the South Pole, consistent with their position within Pangea.

It took several decades and advancements in technology, particularly during the mid-20th century, for Wegener’s hypothesis to gain widespread acceptance. The discovery of seafloor spreading, magnetic striping on the ocean floor, and the identification of subduction zones provided the long-sought mechanism for continental movement. This led to the development of the theory of plate tectonics, which explains that the Earth’s lithosphere is broken into large plates that are constantly moving, driven by convection currents in the underlying mantle. Pangea is now understood as the most recent of several supercontinents that have formed and broken apart throughout Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history. Its breakup, beginning around 175 million years ago, directly led to the formation of the continents and ocean basins we recognize today, profoundly influencing global climate, ocean currents, and the distribution and evolution of life.

Turtle Island: The Indigenous Cosmology

In stark contrast to the scientific narrative of Pangea, the concept of Turtle Island is deeply embedded in the spiritual, cultural, and historical fabric of numerous Indigenous nations across North America. It is not a geological theory but a profound creation story, a name, and a metaphor that encapsulates a worldview centered on interconnectedness, respect, and responsibility for the Earth.

While specific narratives vary widely among nations—including the Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, Lenape, and many others—a common thread describes a primordial time when the world was covered by a great flood. In many versions, a diving animal (often a muskrat or beaver, sometimes other creatures) bravely plunges into the deep waters to retrieve a handful of mud or earth. This small offering is then placed on the back of a giant turtle, which, through divine intervention or the efforts of other beings (like Sky Woman in Haudenosaunee tradition), begins to grow and expand, forming the landmass that is now North America.

The significance of Turtle Island extends far beyond a simple origin myth:

- Creation and Identity: It provides a fundamental explanation for the existence of the land and, by extension, the people who inhabit it. It links Indigenous peoples directly to the land through a shared creation narrative, fostering a deep sense of belonging and identity.

- Spiritual and Cultural Significance: The turtle symbolizes wisdom, longevity, and the sacredness of the Earth. The story teaches that the land is not merely inert property but a living, breathing entity deserving of reverence and protection. It underscores a reciprocal relationship: the Earth sustains life, and humans have a sacred duty to care for it.

- Land Stewardship and Responsibility: The narrative of Turtle Island inherently carries an ethical framework for environmental stewardship. It emphasizes that the land is a gift, not a commodity, and that humans are caretakers, not owners. This worldview informs traditional ecological knowledge and sustainable practices passed down through generations.

- Political and Social Resonance: In contemporary Indigenous movements, "Turtle Island" serves as a powerful pan-Indigenous term, reclaiming the land from colonial names and asserting Indigenous sovereignty, self-determination, and land rights. It represents a collective identity and a shared struggle for environmental justice and the revitalization of Indigenous cultures. As Mohawk scholar Taiaiake Alfred states, "The land is the source of all life and is therefore sacred. We do not own the land; the land owns us." This sentiment encapsulates the core philosophy of Turtle Island.

Divergent Paths, Shared Ground? Comparing and Contrasting

The Pangea and Turtle Island narratives operate on fundamentally different planes of understanding. Pangea is a scientific theory, meticulously constructed from empirical data, geological observation, and the principles of physics and chemistry. It seeks to explain the "how" of Earth’s physical evolution over vast geological timescales, providing a testable and falsifiable explanation for continental movement and formation. Its methodology is rooted in the Western scientific tradition of objective inquiry and evidence-based reasoning.

Turtle Island, conversely, is a cosmological narrative, an origin story, and a spiritual framework. It seeks to explain the "why" of existence, providing meaning, purpose, and an ethical guide for human interaction with the natural world. Its methodology is rooted in oral tradition, spiritual insight, and intergenerational knowledge transfer, emphasizing relationality, respect, and a holistic view of the cosmos. It is not intended to be a geological explanation but a cultural foundation.

Key distinctions include:

- Nature of Knowledge: Scientific (empirical, verifiable, falsifiable, focused on physical processes) vs. Indigenous (holistic, spiritual, experiential, relational, focused on meaning and ethics).

- Purpose: Explanatory (to describe physical phenomena and their mechanisms) vs. Relational/Ethical (to define human identity and responsibility within creation).

- Scope: Global (Pangea describes the entire Earth’s geological history) vs. Continental (Turtle Island specifically refers to North America, though its philosophical implications are universal).

- Temporality: Deep time (Pangea’s breakup spans hundreds of millions of years) vs. Cyclical/Relational time (Turtle Island’s story is an ongoing creation, a living tradition that connects past, present, and future).

While these two frameworks are not directly reconcilable in their literal narratives, they are not necessarily in direct competition either. They represent different ways of knowing and relating to the Earth. One provides the physical blueprint and dynamic history of the planet’s crust; the other offers a spiritual and ethical guide for inhabiting that blueprint.

The Contemporary Relevance

In an era grappling with unprecedented environmental crises, the contrasting yet complementary perspectives of Turtle Island and Pangea hold profound contemporary relevance. The scientific understanding derived from Pangea and plate tectonics is crucial for comprehending natural disasters, predicting geological hazards, and managing resource extraction. It allows us to map the Earth’s deep history and understand the physical forces that shape our world.

However, the Pangea narrative, by itself, often lacks an inherent ethical imperative for care. This is where the wisdom embedded in the Turtle Island cosmology becomes indispensable. As Western societies increasingly recognize the limitations of a purely mechanistic view of nature, Indigenous knowledge systems, with their emphasis on interconnectedness, reciprocity, and stewardship, offer vital pathways toward sustainability. The philosophy of Turtle Island teaches that humans are part of the web of life, not separate from or superior to it, and that our actions have consequences for all creation.

The growing movement towards reconciliation and decolonization includes a recognition of the immense value of Indigenous knowledge. Integrating the scientific understanding of Earth’s physical processes with the spiritual and ethical framework of Turtle Island can lead to a more comprehensive and sustainable approach to environmental challenges. It encourages a dual perspective: appreciating the scientific "how" of Earth’s formation while embracing the Indigenous "why" of our sacred responsibility to it.

Conclusion

Turtle Island and Pangea stand as powerful, albeit distinct, narratives of origin and existence. Pangea, the scientific supercontinent, provides a meticulously constructed geological history of our planet, explaining the dynamic forces that have shaped the land beneath our feet over eons. Turtle Island, the Indigenous cosmology, offers a sacred creation story that defines identity, spiritual connection, and an enduring ethical responsibility for the Earth.

Neither concept diminishes the other. Instead, they enrich our understanding. Pangea gives us the empirical data and the "how-to" guide for Earth’s physical processes. Turtle Island gives us the spiritual context and the "why-to" guide for respectful coexistence. By embracing both, we can gain a fuller, more nuanced appreciation for the ground we walk on—a place of immense geological history and profound spiritual significance, a home that demands both our scientific curiosity and our deepest reverence.