The Unseen Threads: Turtle Island’s Philosophy of Interconnectedness

The land we now call North America has, for millennia, been known to its original inhabitants as Turtle Island. More than just a name derived from ancient creation stories, Turtle Island embodies a profound philosophical worldview: one of radical, inescapable interconnectedness. This philosophy, deeply embedded in the lifeways, languages, and spiritual practices of countless Indigenous nations, offers not merely an alternative way of seeing the world, but a vital, urgent pathway toward global sustainability and harmonious co-existence in an era defined by fragmentation and ecological crisis.

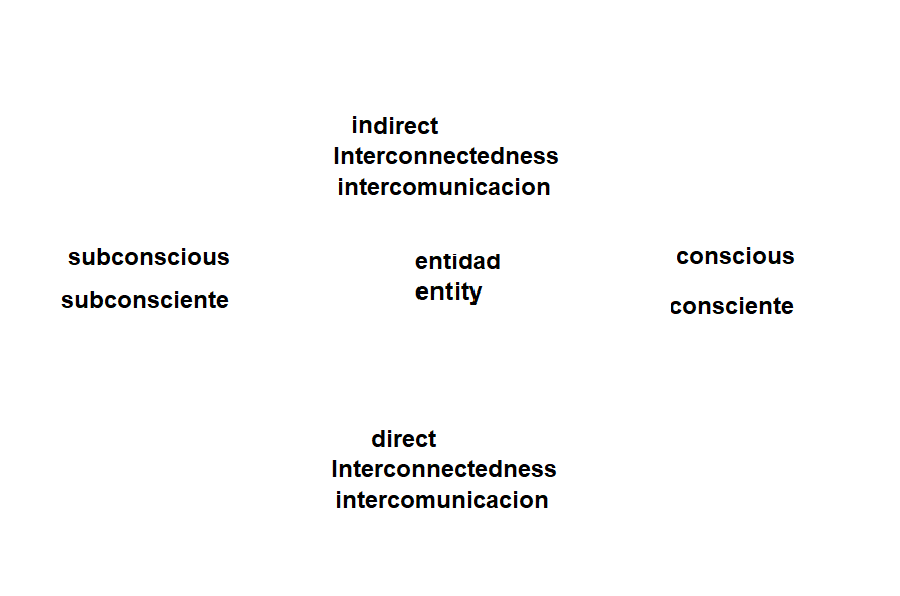

At its core, the Turtle Island philosophy posits that all existence is woven into an intricate, living web. Humans are not masters of this web, but an integral, albeit humble, part of it. This stands in stark contrast to dominant Western paradigms that often place humanity at the apex of a hierarchical order, viewing nature as a resource to be exploited. For Indigenous peoples, the Earth is not a collection of inert matter but a living entity, a sacred grandmother, a provider, and a teacher. Every rock, every stream, every tree, every animal, every human being, every spirit is a relation, deserving of respect, reciprocity, and reverence.

This concept of "All My Relations" (often expressed as Mitakuye Oyasin by the Lakota, though the sentiment is universal across many Indigenous cultures) is not a poetic flourish but a guiding principle for action. It demands an understanding of the ripple effects of every decision. If a river is polluted, it harms not only the fish, but the animals that drink from it, the plants along its banks, the people who rely on it for sustenance, and ultimately, the spirit of the land itself. This holistic understanding compels a profound sense of responsibility. As Indigenous scholar and Potawatomi botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer beautifully articulates, "Knowing that you are a part of something larger than yourself and that you have a contribution to make, is a powerful knowledge."

One of the most powerful manifestations of this interconnectedness is the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) principle of the Seventh Generation. This foundational concept dictates that every decision made today must consider its impact on the seventh generation yet to come. It’s a testament to long-term thinking, a commitment to stewardship that transcends individual lifespans. This isn’t just about environmental protection; it’s about ensuring the spiritual, cultural, and physical well-being of future descendants. It forces a perspective where the present is inextricably linked to the past and the future, where current actions ripple across centuries. Imagine a world where every policy, every business decision, every consumer choice was filtered through the lens of seven generations. The implications for our planet would be transformative.

The creation narratives of Turtle Island themselves underscore this profound interconnectedness. Many stories describe a time when the Earth was covered in water, and a brave turtle offered its back as a foundation for the new land. Animals, often including a muskrat or beaver, then dove to the depths to bring up soil, which was then spread upon the turtle’s back, forming the land. This narrative, shared in various forms by nations like the Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, and Lenape, teaches that the land itself is a gift, formed through the collective effort and sacrifice of multiple beings. It instills a deep sense of gratitude and an understanding that humans are not the sole architects of their world, but beneficiaries of a sacred partnership. The land, therefore, is not merely property to be owned and exploited, but a living relative to be cared for.

This philosophical lens naturally extends to every aspect of Indigenous life. Food systems, for example, are not merely about harvesting but about fostering reciprocal relationships. Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) often involves intricate practices of companion planting, controlled burns, and sustainable harvesting that enhance biodiversity and ensure long-term productivity. The "Three Sisters" — corn, beans, and squash — grown together by many nations, exemplify this interconnectedness: corn provides a stalk for beans to climb, beans fix nitrogen in the soil, and squash leaves shade the ground, retaining moisture and deterring pests. This isn’t just efficient agriculture; it’s a living metaphor for how different elements can support and enrich one another.

However, the wisdom of Turtle Island has been profoundly challenged by colonialism. The imposition of Western legal systems that privatized land, commodified resources, and viewed nature as separate from humanity fractured these ancient bonds of interconnectedness. Indigenous peoples were dispossessed of their lands, their languages suppressed, and their spiritual practices outlawed, all in an effort to sever their relationship with the very source of their philosophy. The devastating consequences are evident today in the ongoing climate crisis, the rampant destruction of ecosystems, and the deep social inequalities that persist.

Yet, despite centuries of oppression, the philosophy of Turtle Island endures. It is being revitalized and shared with renewed urgency, offering crucial insights for navigating the complex challenges of the 21st century. In a world grappling with climate change, biodiversity loss, and social fragmentation, the Indigenous worldview provides a framework for healing and restoration. It teaches us that environmental degradation is not merely a technical problem to be solved with technology, but a spiritual and relational crisis demanding a fundamental shift in our perception of ourselves and our place in the world.

For non-Indigenous people, embracing the Turtle Island philosophy doesn’t mean appropriating Indigenous cultures, but rather learning from their profound wisdom. It means cultivating a deeper sense of place, understanding the ecological history of the land we inhabit, and recognizing the inherent value of all life forms. It involves listening to Indigenous voices, supporting Indigenous sovereignty, and working towards reconciliation. It means re-learning reciprocity, not just with other humans, but with the entire natural world.

The call to action embedded in the Turtle Island philosophy is clear: we must mend the broken threads of interconnectedness. We must move beyond anthropocentric arrogance and embrace our role as responsible relatives within the intricate web of life. By honoring the land, respecting all beings, and considering the well-being of future generations, we can begin to restore balance to our planet and rediscover the profound beauty and wisdom that comes from truly understanding that we are, indeed, "All My Relations." The ancient wisdom of Turtle Island is not a relic of the past; it is a beacon for a sustainable and just future, offering the unseen threads that can weave humanity back into the harmonious fabric of life.