Sovereign Strokes: Turtle Island Art as an Unflinching Political Statement

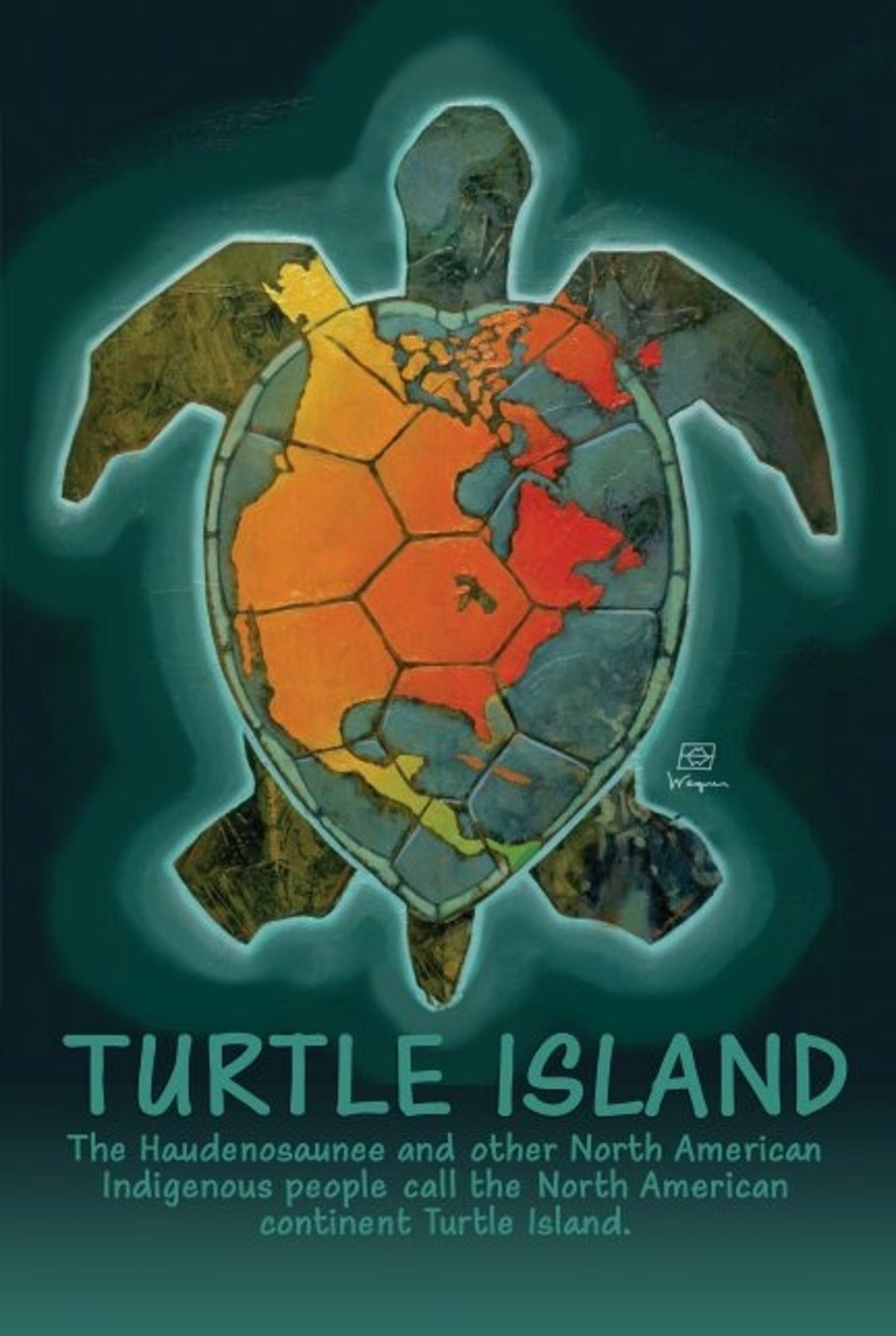

In the vast and varied landscape known as Turtle Island – the Indigenous name for what is commonly referred to as North America – art is rarely, if ever, a mere aesthetic pursuit. It is a profound, living language, a repository of history, a beacon of identity, and an unflinching political statement. From ancient petroglyphs to contemporary digital installations, Indigenous art from Turtle Island intrinsically challenges colonial narratives, asserts sovereignty, demands justice, and celebrates an enduring cultural resilience that defies centuries of attempted erasure.

The very act of creating Indigenous art on Turtle Island is, at its core, an act of political self-determination. For generations, colonial powers sought to dismantle Indigenous cultures, languages, and governance systems. Art, often deemed "primitive" or relegated to ethnographic curiosities, was simultaneously suppressed and appropriated. Yet, despite residential schools, land dispossession, and legislative bans on cultural practices, Indigenous artists persisted. Their continued creation is a powerful refusal to be silenced, a testament to the strength of their nations, and a direct challenge to the notion of Indigenous disappearance. As Anishinaabe artist Robert Houle once stated, "Our art is political because our existence is political." This simple yet profound truth underpins every brushstroke, every carved line, every beaded design.

One of the most potent political statements embedded in Turtle Island art is the assertion of land sovereignty and environmental stewardship. Indigenous peoples have always understood their deep, reciprocal relationship with the land, water, and all living beings. This connection is not merely spiritual; it is a foundational principle of governance, identity, and survival. Colonialism, driven by resource extraction and a commodification of nature, has systematically undermined this relationship, leading to environmental degradation and the dispossession of Indigenous territories.

Contemporary Indigenous artists often confront these issues directly. Works depicting ancestral lands, sacred sites, and traditional knowledge serve as powerful reminders of inherent rights and responsibilities. Christi Belcourt, a Métis artist renowned for her intricate, pointillist-style paintings, frequently depicts flora and fauna with a vibrant reverence, subtly asserting Indigenous land title and ecological wisdom. Her work, such as "Water is Life," directly engages with the struggle against pipeline projects and the protection of vital water sources, aligning art with direct environmental activism. Similarly, the striking protest art that emerged from Standing Rock, where water protectors gathered to resist the Dakota Access Pipeline, showcased a resurgence of traditional imagery alongside contemporary protest graphics, demonstrating the unbreakable link between art, land, and political resistance. These pieces are not merely pretty pictures; they are manifestos for a sustainable future, rooted in millennia of ecological knowledge.

Beyond land, Turtle Island art powerfully addresses identity, representation, and the decolonization of narratives. For too long, Indigenous peoples have been subjected to stereotypical, often dehumanizing, portrayals in mainstream media and art. The "noble savage," the "dying Indian," the romanticized warrior – these tropes served to justify colonial expansion and deny contemporary Indigenous existence. Indigenous artists reclaim the power of representation, creating nuanced, complex, and authentic depictions of themselves, their communities, and their histories.

Kent Monkman, a Cree artist, is a master of this reclamation. His epic, often provocative, paintings reappropriate classical European art styles to insert Indigenous perspectives into historical narratives, often with a mischievous queer trickster figure, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, as a central character. Monkman’s work directly confronts the violence of colonization, the trauma of residential schools, and the ongoing struggles for justice, while simultaneously celebrating Indigenous resilience and challenging gender norms. By inserting Indigenous bodies and experiences into the very canvases that once excluded or misrepresented them, Monkman decolonizes art history itself, forcing viewers to confront uncomfortable truths and re-evaluate their understanding of the past.

The trauma of residential schools and the ongoing legacy of colonialism is another crucial political statement embedded in much of Turtle Island art. These institutions, designed to "kill the Indian in the child," inflicted unimaginable suffering and intergenerational trauma. Art provides a vital space for healing, remembrance, and advocacy. Rebecca Belmore, an Anishinaabe artist, often uses performance and installation to explore themes of violence against Indigenous women, the impact of residential schools, and the resilience of survivors. Her powerful piece "Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother" involved a massive wooden megaphone used to amplify Indigenous voices across significant landscapes, symbolizing the need for Indigenous truths to be heard and acknowledged in public spaces. Such works serve as both memorials and calls to action, urging reconciliation and accountability.

Similarly, the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People (MMIWG2S) finds poignant expression in art. The red dress movement, initiated by Métis artist Jaime Black, uses empty red dresses hung in public spaces to symbolize the thousands of MMIWG2S, making their absence visible and demanding justice. These installations are stark political statements, condemning systemic violence and calling for meaningful change in policy and public consciousness. They transform art into a powerful tool for social justice advocacy, forcing a national conversation around a crisis that has been historically ignored.

Furthermore, Turtle Island art is a powerful assertion of cultural revitalization and linguistic preservation. Many Indigenous languages are endangered, a direct consequence of colonial policies. Art, whether through visual symbols, storytelling, or the incorporation of Indigenous languages, plays a critical role in strengthening cultural identity and transmitting knowledge across generations. The intricate beadwork of the Great Lakes region, the vibrant button blankets of the Northwest Coast, the geometric patterns of Plains painting – these are not merely decorative. Each design, each colour, each technique carries layers of meaning, ancestral stories, clan histories, and spiritual teachings. Their continued practice and evolution are acts of resistance against cultural assimilation, reaffirming distinct national identities and demonstrating the enduring vitality of Indigenous knowledge systems.

The political dimension of Turtle Island art also lies in its capacity to foster dialogue and education. For non-Indigenous audiences, this art can be a transformative entry point into understanding Indigenous perspectives, histories, and ongoing struggles. It challenges complacency, dismantles ignorance, and can cultivate empathy. By presenting Indigenous experiences directly and authentically, artists invite viewers to confront their own biases, question inherited assumptions, and engage with the complexities of decolonization. Art becomes a bridge, albeit one built on difficult truths, towards a more just and equitable future.

In essence, Turtle Island art functions as a multi-faceted political declaration. It is a testament to survival, a demand for justice, a reclamation of narrative, and a blueprint for a future where Indigenous sovereignty and cultural diversity are not just acknowledged but celebrated. It speaks to the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples to their lands, their cultures, and their self-determination. It is a living, breathing testament that despite centuries of oppression, the creative spirit of Turtle Island remains vibrant, resilient, and unapologetically political. Each piece, whether traditional or contemporary, carries the weight of history and the promise of a sovereign future, asserting that Indigenous peoples are here, they are thriving, and their voices, articulated through art, will continue to shape the destiny of this continent.