Turtle Island and the Evolving Dialogue of Land Acknowledgements

Across North America, from the solemn opening of academic conferences to the boisterous start of sporting events, a ritual has taken root: the land acknowledgement. These statements, often delivered with earnest intent, are meant to recognize the Indigenous peoples on whose traditional territories an event is taking place. But what began as a critical step towards reconciliation has evolved into a complex, often debated practice, rooted deeply in the ancient concept of Turtle Island—a name far more profound than mere geography.

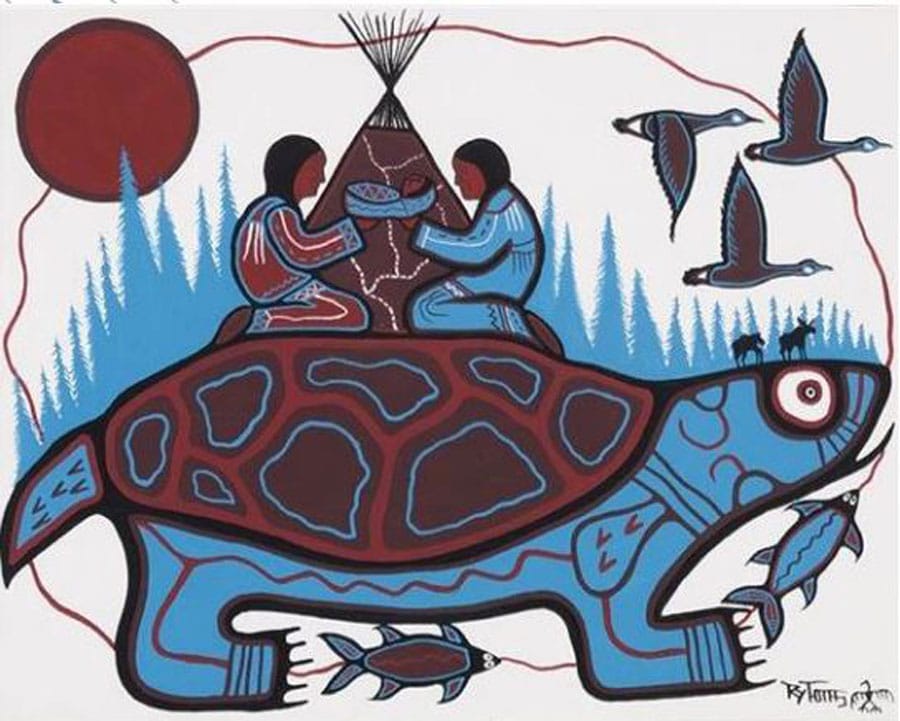

To understand the full weight of a land acknowledgement, one must first grasp the significance of Turtle Island. For many Indigenous nations, particularly those in the Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee traditions, Turtle Island is not merely a metaphor for North America; it is the original name, steeped in creation stories and spiritual teachings. These narratives, passed down through generations, speak of a time when the world was covered in water, and a brave muskrat or otter brought up earth from the depths, which was then placed on the back of a giant turtle, forming the land as we know it today.

This foundational narrative illustrates an inherent relationship between Indigenous peoples and the land—one of profound respect, stewardship, and spiritual connection, not ownership in the Western sense. "The land is not just a resource; it is our relative, our mother," explains Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, a Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar and writer. "It holds our histories, our languages, our ceremonies." The concept of Turtle Island, therefore, carries with it an entire worldview that predates colonial borders, names, and property laws. It speaks to millennia of Indigenous presence, governance, and vibrant cultures that thrived long before European contact.

The shift from "North America" to "Turtle Island" in these acknowledgements is a deliberate act of decolonization. It challenges the imposed narratives that erase Indigenous history and sovereignty, asserting instead a deep, enduring connection to the land that existed and continues to exist.

The Genesis of Acknowledgement: From Oblivion to Obligation

The practice of land acknowledgements, while seemingly contemporary, draws from ancient Indigenous protocols of welcome and respect for visiting other nations’ territories. In its modern form, its widespread adoption gained significant momentum in Canada following the 2015 release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada’s 94 Calls to Action. Though not explicitly listed, the spirit of the calls—particularly those related to education, public awareness, and reconciliation—provided a powerful impetus. Similar movements and Indigenous advocacy in the United States, Australia, and New Zealand also contributed to their rise.

The core intent of a land acknowledgement is multi-faceted:

- Recognition of Sovereignty: To acknowledge that Indigenous peoples are the original and ongoing stewards of the land, asserting their inherent rights and nationhood.

- Historical Truth-Telling: To recognize the historical and ongoing impacts of colonialism, including dispossession, forced removal, and the suppression of Indigenous cultures.

- Education and Awareness: To inform non-Indigenous people about the specific Indigenous nations whose territories they occupy, fostering a deeper understanding of local history.

- A Step Towards Reconciliation: To signal a commitment to building respectful relationships and advancing reconciliation efforts.

Ideally, an acknowledgement names the specific Indigenous nations who are the traditional and treaty holders of the land, mentions whether the territory is unceded (never surrendered by treaty) or covered by treaty, and expresses gratitude for their stewardship. It is meant to be a moment of pause, reflection, and intentional engagement with the truth of the past and the responsibilities of the present.

The Perils of Performance: When Acknowledgement Falls Short

However, as land acknowledgements have become more commonplace, they have also drawn criticism, particularly from Indigenous communities themselves. A significant concern is the risk of them becoming performative—a box to check, a rote recitation devoid of genuine meaning or action.

Hayden King, Anishinaabe scholar and executive director of the Yellowhead Institute, has been a prominent voice on this issue. He notes, "An acknowledgement that doesn’t lead to action is simply a performance. It can become an empty ritual that alleviates settler guilt without actually addressing Indigenous rights or systemic injustices." When an acknowledgement is delivered without sincerity, personal reflection, or a commitment to tangible change, it risks reinforcing the very colonial structures it purports to challenge.

Common pitfalls include:

- Generic Statements: Using broad, unresearched phrases like "We acknowledge the Indigenous peoples of this land" without naming specific nations, languages, or treaties. This erases the diversity and distinctiveness of hundreds of Indigenous cultures.

- Lack of Personal Connection: Reading a pre-written script without understanding its meaning or making it relevant to the speaker or event.

- Absence of Action: Failing to follow up the acknowledgement with concrete steps towards reconciliation, such as supporting Indigenous-led initiatives, advocating for Indigenous rights, or engaging in personal education.

- Tokenism: Using acknowledgements as a substitute for meaningful engagement, representation, or addressing systemic inequities.

For many Indigenous peoples, hearing an acknowledgement followed by business-as-usual, without any genuine effort to address land rights, economic disparities, or cultural revitalization, can be more frustrating than empowering. It highlights the vast gap between symbolic gestures and substantive change.

Beyond Words: Towards Meaningful Engagement

The challenge, then, is to elevate land acknowledgements from mere words to meaningful actions. This requires a deeper commitment from individuals and institutions alike.

1. Research and Specificity: Before delivering an acknowledgement, one must research the specific Indigenous nations whose territories they are on. Tools like Native-Land.ca or local Indigenous organizations can help. Learning proper pronunciations of names and understanding local history is crucial. For example, in what is colonially known as Toronto, Canada, one might acknowledge it as the traditional territory of the Anishinaabeg, Haudenosaunee, and Huron-Wendat peoples, among others, and that it is covered by Treaty 13 and the Williams Treaties.

2. Personalization and Intent: An acknowledgement should be delivered with sincerity and personal reflection. How does the speaker’s presence on this land connect to their work or the event? What does it mean to them personally to acknowledge this history? Making it an active statement of gratitude and responsibility, rather than a passive recitation, is key.

3. Education and Continuous Learning: A land acknowledgement should be a starting point, not an endpoint. It should spur ongoing education about Indigenous histories, cultures, and contemporary issues. This includes learning about treaties, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), and the impacts of residential schools or boarding schools.

4. Tangible Action and Allyship: This is the most crucial step. Meaningful engagement includes:

- Supporting Indigenous Initiatives: Donating to Indigenous-led organizations, businesses, and cultural programs.

- Advocating for Rights: Supporting policies that uphold Indigenous sovereignty, land rights, and self-determination. This includes the "Land Back" movement, which seeks to return ancestral lands to Indigenous peoples.

- Challenging Colonial Structures: Actively working to dismantle systemic racism and inequities within institutions and society at large.

- Building Relationships: Seeking opportunities to connect with local Indigenous communities, listen to their perspectives, and build respectful relationships.

As Chelsea Vowel, a Métis writer and educator, articulates, "An acknowledgement is not a magic spell. It is a moment to ground oneself in the reality of where you are and to reflect on what your responsibilities are in that space."

The Path Forward: A Journey of Decolonization

Ultimately, land acknowledgements are but one small, albeit significant, component of the much larger, complex, and ongoing process of decolonization and reconciliation. They serve as a visible reminder that we are all living on Indigenous lands, and that the history of these lands is far richer and more intricate than colonial narratives often suggest.

By embracing the spirit of Turtle Island, recognizing the profound and enduring connection of Indigenous peoples to their ancestral territories, and moving beyond performative gestures towards genuine action, land acknowledgements can truly become powerful tools for change. They can foster environments where Indigenous voices are centered, rights are respected, and a more just and equitable future for all inhabitants of Turtle Island can begin to emerge. The journey is long and demanding, but each thoughtful acknowledgement, each informed action, brings us closer to a future rooted in truth, respect, and mutual understanding.