The Shifting Sands of Empire: Fort Stanwix and the Illusions of Peace

Fort Stanwix, New York, 1768 – In the chilling winds of autumn, a drama of imperial ambition, Indigenous strategy, and colonial hunger unfolded at a remote British outpost. For weeks, a grand council convened, drawing together representatives of the British Crown, colonial land speculators, and the powerful Iroquois Confederacy. What emerged from these negotiations, the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, was hailed by many at the time as a triumph of diplomacy, a definitive solution to the volatile frontier. Yet, beneath the veneer of accord lay a tapestry of deception, miscalculation, and a profound misunderstanding of Indigenous sovereignty, destined to unravel and ultimately ignite further conflict, laying crucial groundwork for the American Revolution and the relentless westward expansion that followed.

To grasp the full weight of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, one must journey back into the tumultuous decade preceding its signing. The Seven Years’ War (known as the French and Indian War in North America) had concluded in 1763, redrawing the map of a continent. Britain emerged victorious, seizing vast territories from France, including Canada and the lands east of the Mississippi River. But this victory came at a staggering cost. The war had nearly bankrupted the British treasury, and it had fundamentally altered the delicate balance of power between European empires and Native American nations.

For generations, the Iroquois Confederacy – the Haudenosaunee, comprising the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and later, the Tuscarora – had masterfully navigated this complex geopolitical landscape. Positioned strategically between the French and British empires, they had perfected a diplomacy of neutrality, playing one power against the other to preserve their own autonomy and influence. They were, in essence, the "gatekeepers" to the vast interior, their approval often necessary for European incursions. However, with the French removed, this strategic leverage diminished significantly. The British now stood as the sole dominant European power, and their policies began to reflect this new reality.

The immediate aftermath of the French and Indian War was anything but peaceful. Native American nations, many of whom had fought alongside the French or felt their lands increasingly threatened by British expansion, rose up in what became known as Pontiac’s War (1763-1766). Led by the Ottawa chief Pontiac, a coalition of tribes – including the Ottawa, Delaware, Shawnee, and others – launched devastating attacks on British forts and settlements across the Great Lakes region and Ohio Valley. This fierce resistance underscored the deep resentment over British encroachment and their perceived arrogance. It shattered any illusions the British might have held about easily controlling their newly acquired territories and forced London to reconsider its frontier policy.

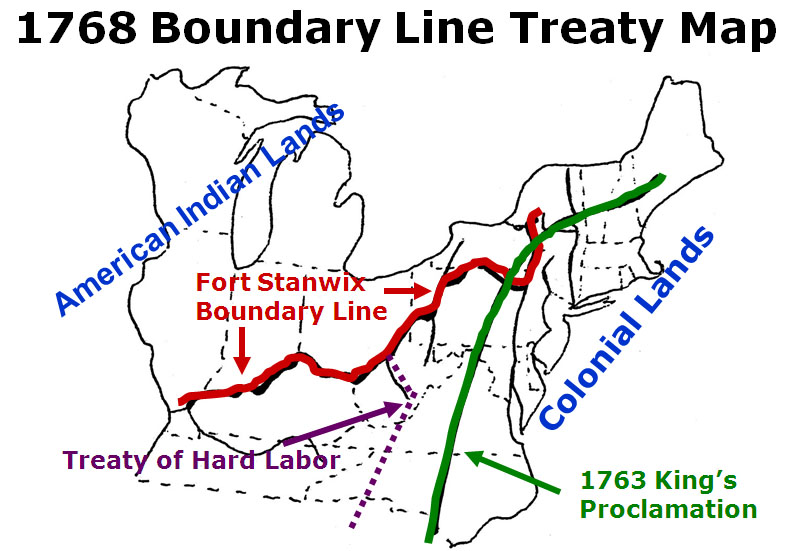

In response to Pontiac’s War and the escalating tensions, the British Crown issued the Proclamation of 1763. This landmark decree prohibited colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains, designating the lands beyond as "Indian Territory." Its intentions were multifaceted: to pacify Native American nations, prevent further costly conflicts, and to bring the unruly colonial expansion under imperial control. However, for land-hungry colonists and powerful land speculation companies, the Proclamation Line was an infuriating impediment, a temporary measure to be circumvented, not respected. Its very existence fueled resentment against British authority and spurred a desire to "legally" push the boundary westward.

This was the volatile backdrop against which Sir William Johnson, the influential British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern Department, began orchestrating the grand council at Fort Stanwix. Johnson, a complex figure, was uniquely suited for the task. Having lived among the Mohawk, he spoke their language, understood their customs, and had even married a Mohawk woman, Molly Brant. He wielded considerable influence within the Confederacy, though his primary loyalty remained, ultimately, with the Crown. His mission was clear: establish a new, permanent boundary line that would satisfy colonial demands for land, stabilize the frontier, and, crucially, do so in a manner that appeared legitimate to the Native Americans.

The negotiations at Fort Stanwix in October and November of 1768 were a spectacle of power and persuasion. Over 3,000 people gathered – British officials, colonial delegates from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Virginia, and representatives from the Six Nations. Johnson employed a combination of diplomatic skill, lavish gifts (including wampum belts, blankets, tools, and a staggering sum of £10,000 sterling, equivalent to millions today), and thinly veiled threats to achieve his aims.

For the Iroquois, particularly the older, more conservative leaders like the Mohawk chief Hendrick Peters Theyanoguin (King Hendrick), the situation was fraught with difficult choices. Their traditional power was waning, their strategic advantage gone. They faced relentless pressure from colonial expansion and the real threat of military reprisals if they resisted. Their strategy, therefore, was to consolidate their remaining power and, paradoxically, to sell off vast tracts of land they did not actively inhabit or control, particularly in the Ohio Valley. Their hope was to divert the flood of colonial settlement away from their own core territories in present-day New York and to secure a permanent, protected homeland. They believed that by ceding these western lands, they would create a buffer zone and gain British recognition and protection for their remaining domains.

The treaty ultimately pushed the boundary line far to the west, extending it down the Ohio River to the Tennessee River. The land ceded was immense, encompassing much of present-day Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky, and significant portions of Ohio. This was not merely a matter of shifting lines on a map; it was a monumental transfer of territory, opening up vast new regions for colonial settlement and speculation.

However, the fatal flaw of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix lay in a fundamental deception: the Iroquois, while a powerful confederacy, did not hold sovereign title over all the lands they ceded. Much of the Ohio Valley was the ancestral territory of other Algonquian-speaking nations, notably the Shawnee, Delaware, and Mingo. These tribes, who were the actual occupants of the lands being sold, were either not present at Fort Stanwix, or their few representatives lacked the authority to speak for their entire nations. From their perspective, the Iroquois had no right to sell their hunting grounds and villages, and the British had no right to accept such a fraudulent transaction.

As historian Colin G. Calloway notes in "The Scratch of a Pen: 1763 and the Transformation of North America," the treaty was "a classic example of divide and rule, by which the British obtained land for settlement and created an enduring rift between the Iroquois and the Ohio Indians." The Iroquois, in their desperate attempt to save themselves, had effectively thrown their western neighbors under the colonial bus.

The immediate aftermath of Fort Stanwix was a mixed bag. For the British and the colonies, it was a moment of apparent triumph. Land companies rejoiced, and settlers, emboldened by what they perceived as a legal right, streamed across the new boundary line. Sir William Johnson believed he had secured peace and opened the door for orderly expansion.

But for the Shawnee, Delaware, and Mingo, the treaty was a declaration of war. They refused to recognize its legitimacy, viewing it as a blatant act of dispossession. The "peace" of Fort Stanwix was, in reality, a temporary illusion, a postponement of inevitable conflict. Within a few years, tensions in the Ohio Valley would erupt into Lord Dunmore’s War (1774), a bitter conflict between Virginia militiamen and the Shawnee and Mingo, directly fueled by the land claims solidified at Fort Stanwix.

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix, therefore, holds profound significance in American history. It not only failed to bring lasting peace to the frontier but actively sowed the seeds of future conflicts. It demonstrated the British Crown’s inability or unwillingness to enforce its own Proclamation of 1763, further alienating colonists who saw imperial policy as inconsistent and weak. It revealed the ruthless efficiency of colonial land speculation and the cynical manipulation of Indigenous politics.

More broadly, it stands as a stark testament to the relentless pressure of westward expansion and the tragic consequences for Native American nations. It was an early, pivotal example of how European powers (and later, the United States) would repeatedly exploit divisions among Indigenous peoples, negotiate treaties that were fundamentally unjust, and ultimately disregard those treaties when they no longer served their interests. The legacy of Fort Stanwix is one of broken promises, cultural displacement, and the enduring struggle for land and sovereignty that continues to shape the narrative of North America. It was not a treaty of peace, but a strategic maneuver that merely shifted the battleground, paving the way for the coming storm of revolution and the continued unraveling of Indigenous control over their ancestral lands.