The Enduring Tapestry of Treaties: Unravelling Land Agreements on Turtle Island

Turtle Island, the Indigenous name for what is largely known as North America, is a landscape profoundly shaped by a complex, often contentious, web of treaties and land agreements. Far from mere historical relics, these documents and the oral traditions that underpin them are living instruments, defining the foundational relationship – or the lack thereof – between Indigenous nations and settler governments. To understand Turtle Island today is to grapple with the promises made, the promises broken, and the ongoing struggle for justice and self-determination that is inextricably linked to these agreements.

The story of treaties on Turtle Island is not monolithic; it is a tapestry woven with distinct threads of diplomacy, deception, and resilience stretching back centuries before the formal establishment of colonial states. Prior to European contact, Indigenous nations had sophisticated systems of governance, law, and land stewardship. Their relationships with each other, and with the land, were often formalized through protocols, ceremonies, and instruments like wampum belts, which served as living documents recording agreements, histories, and laws.

One of the most profound examples of pre-colonial diplomacy and a cornerstone for understanding Indigenous treaty perspectives is the Two Row Wampum Belt (Kaswentha) of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Dating back to 1613 with Dutch settlers, this belt visually represents a foundational philosophy: two parallel rows of purple beads on a white background. The purple rows symbolize two distinct vessels—a Native canoe and a European ship—traveling side-by-side down the river of life. Each vessel contains its own laws, customs, and peoples, never to steer into the other’s path. This agreement, often reiterated with subsequent European powers, encapsulated a vision of respectful coexistence and non-interference, a "nation-to-nation" relationship that Indigenous peoples sought to extend to all newcomers. It speaks to a clear Indigenous understanding of sovereignty and a willingness to share, not surrender.

The arrival of European powers, driven by mercantilism and later imperial ambitions, fundamentally altered this landscape. Initial interactions often involved trade and alliances, particularly in the fur trade era. Indigenous nations, possessing extensive knowledge of the land and its resources, were crucial partners. Early agreements were often alliances of mutual benefit, focused on peace and shared access rather than outright land cession.

A pivotal, albeit deeply flawed, moment in the Crown’s approach to Indigenous land was the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Issued by King George III after Britain’s victory in the Seven Years’ War, it recognized Indigenous title to vast territories not already ceded or purchased by the Crown. It stipulated that only the Crown could negotiate for Indigenous lands, establishing a formal process for land acquisition. While often hailed as an Indigenous "bill of rights," its primary intent was to prevent westward expansion by settlers, thereby avoiding costly conflicts and securing the lucrative fur trade. Indigenous peoples saw it as a recognition of their inherent rights, while the Crown viewed it as a temporary measure to manage its burgeoning colonial empire. This inherent tension between Indigenous and Crown interpretations would become a recurring theme in treaty-making.

As settler populations grew and expansionist pressures mounted, the nature of agreements shifted dramatically. In what is now Eastern Canada, the Peace and Friendship Treaties (1725-1779) were signed between the British Crown and the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), and Passamaquoddy peoples. Unlike later treaties, these agreements did not involve the surrender of land. Instead, they focused on establishing peace, defining hunting and fishing rights, and regulating trade. However, the Crown quickly reinterpreted these as military alliances and land cessions, ignoring the spirit of shared use and mutual respect that Indigenous signatories understood. This fundamental divergence in understanding continues to fuel legal battles and calls for treaty implementation today.

Further west, in Upper Canada (now Ontario), a series of treaties from the late 18th and early 19th centuries facilitated agricultural settlement. These "land surrender" treaties, such as the Mississauga Purchase (1784) and the Robinson Treaties (1850), often involved the exchange of vast tracts of land for annuities, small reserves, and the retention of hunting and fishing rights. While they explicitly mentioned land cession, Indigenous signatories often believed they were agreeing to share the land, not relinquish their inherent connection to it. The concept of "selling" land was alien to many Indigenous worldviews, which viewed land as a communal trust, not a commodity.

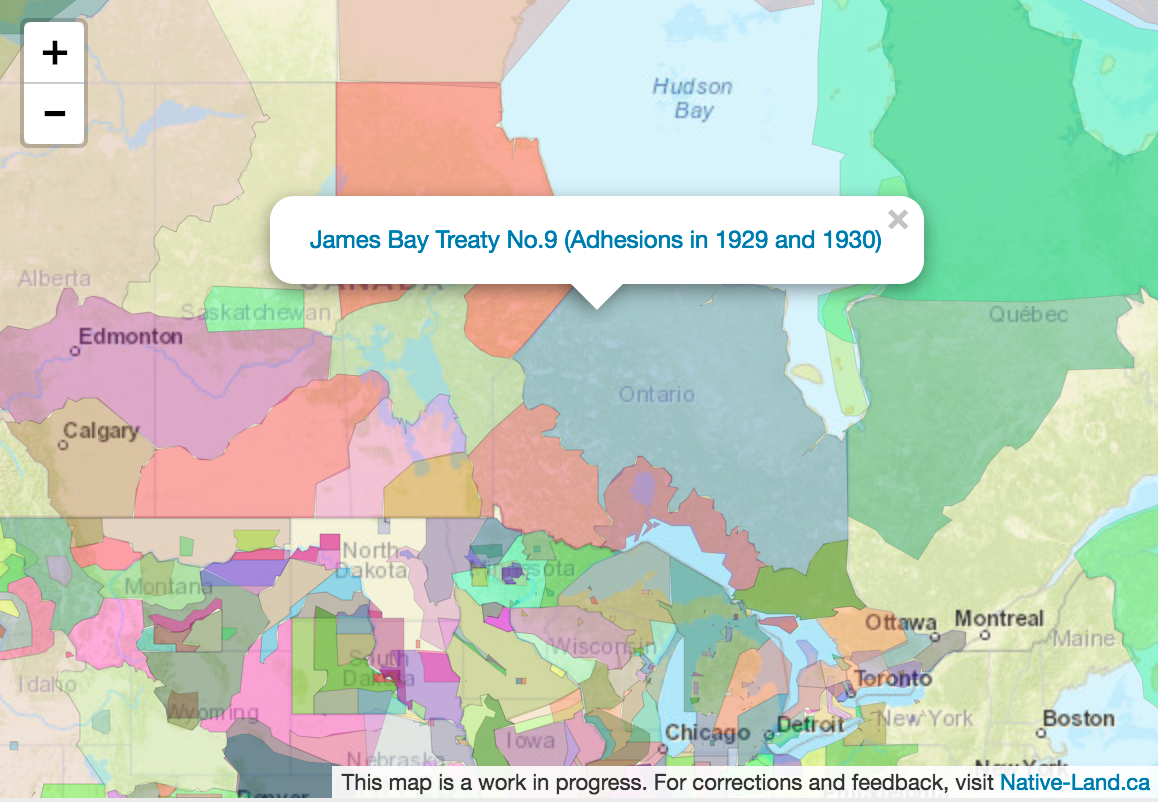

The most extensive and impactful series of agreements were the Numbered Treaties (Treaties 1 to 11), signed between 1871 and 1921 across the Prairies, parts of British Columbia, and the North. These treaties, covering an immense geographical area, were instrumental in facilitating Canada’s westward expansion, agricultural settlement, resource extraction (timber, minerals, oil), and the construction of the transcontinental railway.

The context for the Numbered Treaties was stark: buffalo populations were dwindling, European diseases had ravaged Indigenous communities, and the specter of American expansion loomed. The Crown, eager to secure "clear title" to the land, promised reserves, annuities, agricultural equipment, education, and the continued right to hunt, fish, and trap over ceded territories. However, the negotiations were rife with misunderstandings and power imbalances. Indigenous leaders, facing immense pressure and often negotiating under duress, understood these agreements as peace treaties that would allow for shared use of the land and provide assistance during a time of great change, while preserving their traditional way of life. They saw the reserves as homelands, not isolated parcels.

The Crown, on the other hand, documented these treaties in English, focusing on the "surrender" of Indigenous title and the establishment of "Indian reserves" as segregated parcels for Indigenous peoples. The written text often omitted crucial oral promises made by treaty commissioners regarding healthcare, education, and the inviolability of traditional hunting and fishing rights. This profound disconnect between the "spirit and intent" of the treaties (as understood by Indigenous signatories) and the "letter of the law" (as interpreted by the Crown) became the enduring legacy of the Numbered Treaties.

Following the signing of these treaties, the Canadian government enacted the Indian Act (1876), a piece of legislation that consolidated all previous laws concerning Indigenous peoples and became the primary instrument of assimilation and control. The Act imposed a foreign governance structure, criminalized Indigenous spiritual practices, regulated every aspect of Indigenous life, and eventually led to the establishment of the residential school system—a direct assault on Indigenous culture, language, and family structures. The promises of the treaties were systematically undermined, leading to widespread poverty, dispossession, and the erosion of Indigenous self-governance.

In the United States, a similar pattern unfolded, though with distinct legal frameworks. Hundreds of treaties were signed between the U.S. government and various Indigenous nations, often resulting in the ceding of vast territories in exchange for reserves, annuities, and services. The U.S. Supreme Court, in cases like Worcester v. Georgia (1832), recognized Indigenous nations as "distinct political communities, having territorial boundaries, within which their authority is exclusive." However, this legal recognition often failed to prevent forced removals, land grabs, and the breaking of treaty promises, most infamously exemplified by the "Trail of Tears."

The mid-20th century marked a turning point. Indigenous peoples, despite enduring generations of colonial policies, began to assert their rights more forcefully. Legal challenges emerged, pushing colonial governments to re-evaluate their responsibilities. In Canada, the landmark Calder decision (1973) by the Supreme Court acknowledged the existence of Aboriginal title, even where no treaties had been signed. This opened the door for modern treaty-making, known as Comprehensive Land Claims Agreements.

These modern treaties, like the Nisga’a Final Agreement (1998) in British Columbia or the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (1993), are complex, constitutionally protected agreements that resolve outstanding Aboriginal title. They typically involve a combination of land ownership, financial compensation, resource co-management, and self-government provisions. While often seen as a path to reconciliation, they are not without controversy, particularly concerning clauses that "cede, release, and surrender" Aboriginal title, which some Indigenous nations view as a continuation of historical extinguishment. However, more recent agreements are moving towards "modification" of title rather than outright extinguishment, reflecting a more nuanced approach.

Alongside comprehensive claims, Specific Claims address past grievances arising from the breach of existing treaties or other lawful obligations by the Crown. These claims, often involving historical mismanagement of Indigenous assets or the illegal expropriation of reserve lands, are vital for correcting historical injustices.

The legal landscape continued to evolve with landmark decisions such as Delgamuukw v. British Columbia (1997), which affirmed that Aboriginal title is a communal right to land based on prior occupation and must be proven by oral history and traditional practices. Even more recently, Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia (2014) marked the first time the Supreme Court of Canada declared Aboriginal title to a specific tract of land, setting a new precedent for Indigenous land rights.

Today, the dialogue around treaties on Turtle Island is dominated by the pursuit of reconciliation. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), in its 94 Calls to Action, explicitly emphasized the vital importance of honouring treaties as "living documents" and establishing a "nation-to-nation" relationship based on respect and partnership. The adoption of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) further provides an international framework for upholding Indigenous rights, including the right to self-determination and free, prior, and informed consent regarding resource development on their traditional territories.

The journey towards fully realizing the spirit and intent of treaties is far from over. It requires not just legal recognition but a fundamental shift in mindset within settler societies. It demands treaty education, understanding the historical context, acknowledging the profound injustices, and actively working towards a future where the promises of coexistence, mutual respect, and shared prosperity are genuinely fulfilled. The tapestry of treaties on Turtle Island, once frayed by colonial ambition, is slowly being rewoven, thread by painstaking thread, towards a more just and equitable future for all who call this land home.