From Earth to Essence: The Enduring Art of Traditional Navajo Pottery

In the vast, ancient landscapes of the American Southwest, where the wind whispers through sandstone canyons and the spirit of the Diné (Navajo people) runs deep, lies a profound artistic tradition: the making of Navajo pottery. Unlike the more widely recognized painted pottery of their Pueblo neighbors, traditional Navajo ceramics stand apart, distinguished by their unadorned surfaces, earthy tones, and the distinctive sheen and aroma of piñon pitch. This is not merely a craft; it is a spiritual journey, a tangible connection to the land, and a living testament to resilience and cultural identity. To understand Navajo pottery is to understand a process steeped in ceremony, patience, and a deep reverence for the materials bestowed by Mother Earth.

The creation of a Navajo pot begins not in a studio, but in the earth itself. Traditional potters, often women, possess an intimate knowledge of their ancestral lands, identifying specific clay deposits that yield the desired quality and color. This is not a random excavation; it is a sacred act. Before disturbing the earth, prayers are offered, acknowledging the spirit of the clay and seeking permission to gather it. "You have to ask the earth, respect the earth, before you take from her," shares one elder potter, her words echoing generations of reverence. The chosen clay, typically found in riverbeds or specific geological formations, is then carefully extracted, often in chunks.

Once gathered, the raw clay undergoes a meticulous preparation process. It is first dried in the sun, then broken down into smaller pieces, and laboriously crushed into a fine powder. This powder is then sifted through a screen or cloth to remove impurities like pebbles, roots, and sand, ensuring a smooth, consistent texture. The next crucial step is the addition of temper. Temper, such as finely ground volcanic ash, crushed sandstone, or even pulverized potsherds from broken vessels, is mixed with the clay. This addition is vital; it prevents the clay from cracking during drying and firing, and it provides structural integrity to the finished piece. The proportions are not measured with scientific precision but with an intuitive knowledge passed down through generations, a sense of "feel" that only comes from years of practice. Water is then slowly added, and the mixture is kneaded until it reaches the perfect plasticity – pliable enough to shape, yet firm enough to hold its form.

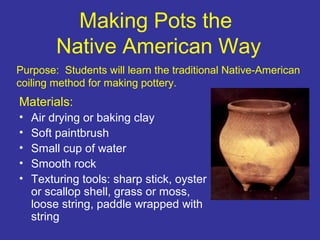

With the clay prepared, the potter begins the transformative process of shaping. Unlike many contemporary potters who utilize a wheel, traditional Navajo pottery is built entirely by hand, primarily using the coiling method. A flat base is formed, either by pressing out a slab or by starting with a small, solid sphere and pinching it outwards. From this foundation, long, snake-like coils of clay are rolled out between the palms. Each coil is then carefully placed upon the rim of the previous one, and seamlessly blended into it using the fingers and simple tools like gourd shards or smoothed pieces of wood. This methodical building, coil by coil, allows the potter to control the vessel’s form, gradually expanding or contracting the walls to achieve the desired shape – be it a wide-mouthed cooking pot, a graceful water jar, or the distinctive double-mouthed wedding vase.

This manual process demands immense patience, skill, and an innate sense of symmetry. The potter often works in stages, allowing sections to firm up slightly before adding more coils, preventing the soft clay from collapsing under its own weight. As the vessel takes shape, its surfaces are meticulously scraped and smoothed, both inside and out, removing any visible coil marks and refining the contours. The beauty of traditional Navajo pottery lies in its form and texture, rather than applied decoration. The unadorned surface, often burnished to a subtle sheen with a smooth stone, allows the natural beauty of the clay and the skilled hand of the potter to speak for themselves. This aesthetic choice starkly differentiates it from the vibrant, painted designs characteristic of Pueblo pottery.

Once the desired form is achieved and smoothed, the unfired vessel, known as a "greenware" pot, must undergo a slow and careful drying process. This can take several days or even weeks, depending on the size of the pot and atmospheric conditions. Rushing this stage risks cracking and irreparable damage. The potter often places the pot in a shaded, well-ventilated area, turning it periodically to ensure even drying.

The penultimate stage, and arguably the most dramatic, is the firing. Traditional Navajo pottery is fired outdoors, without the use of a modern kiln. A shallow pit or a simple, open-air structure of stones may be used, but often the pots are simply arranged on the ground, surrounded by fuel. The choice of fuel is crucial and often includes cedar, piñon, or juniper wood, as well as dried animal dung, particularly sheep dung, which provides a long, even burn. The pots are carefully stacked, often inverted, and then covered with more fuel. The fire is ignited, and the potter meticulously monitors the flames and smoke, adjusting the fuel as needed to maintain the optimal temperature. This is a highly skilled art, as too much heat can cause cracking, while too little will result in a weak, underfired pot.

During the firing process, the intense heat transforms the raw clay into durable ceramic. As the fire consumes the fuel, it leaves behind distinctive black smudges and patterns on the surface of the pots, known as "fire clouds." These natural markings, far from being imperfections, are highly valued by Navajo potters and collectors alike. They are seen as unique gifts from the fire, imbuing each pot with its own story and character, a direct result of the elemental interaction. The spiritual significance of fire in Navajo culture, representing purification and transformation, further elevates this stage beyond mere technique.

What truly sets traditional Navajo pottery apart, and gives it its distinctive character, is the final step: the application of piñon pitch. While the pots are still warm from the firing, or sometimes gently reheated, melted piñon pine pitch is carefully rubbed onto the exterior surface. This sticky, aromatic resin penetrates the porous clay, serving multiple crucial functions. Firstly, it waterproofs the pot, making it suitable for holding liquids like water or herbal medicines. Secondly, it strengthens the vessel, adding a layer of durability. Thirdly, it imparts a beautiful, dark, lustrous sheen that deepens with age and handling. And finally, and perhaps most uniquely, it gives the pottery a warm, earthy, and distinctly piney aroma that is instantly recognizable and deeply evocative of the Southwest landscape.

The application of piñon pitch is not merely a utilitarian act; it is also imbued with ceremonial significance. In many traditional Navajo healing ceremonies, particularly the Blessingway, pottery plays a vital role. Water jars sealed with piñon pitch are used to hold sacred water, symbolizing life and purity. The wedding vase, with its two spouts, is used in marriage ceremonies, representing the two individuals coming together as one. The aroma of the piñon pitch itself is considered sacred, believed to cleanse and protect.

The making of traditional Navajo pottery is more than just the sum of its parts; it is a profound cultural expression, a direct link to ancestral knowledge and the Diné way of life. Each pot embodies the spirit of the earth from which its clay was drawn, the patience and skill of the potter’s hands, and the transformative power of fire. In an increasingly modern world, the continuation of this tradition faces challenges, including the availability of natural materials and the economic pressures of contemporary life. Yet, dedicated Navajo potters continue to practice and teach these ancient methods, ensuring that the whisper of the wind, the scent of piñon, and the enduring beauty of Earth’s embrace continue to be molded into vessels that carry not just water or food, but the very essence of Diné heritage. It is a powerful reminder that true art, born of the earth and shaped by human hands, can transcend time, speaking volumes about the people who create it and the land that sustains them.