The Enduring Architecture of Harmony: Traditional Navajo Hogan Construction

The Navajo hogan is far more than a simple dwelling; it is a profound architectural embodiment of Diné philosophy, cosmology, and a living connection to the land. For centuries, these structures have served as the fundamental homes and spiritual anchors for the Navajo people, meticulously crafted to reflect their worldview and ensure harmony with the natural world. This article delves into the intricate construction methods, cultural significance, and enduring legacy of traditional Navajo housing.

A Sacred Foundation: Cosmology and Purpose

At its core, the hogan is a physical manifestation of Hózhó, the Navajo concept of beauty, balance, and harmony that encompasses all aspects of existence. Every element of its design and orientation is steeped in spiritual meaning, connecting the inhabitants directly to the forces of the universe. The hogan is often described as a microcosm of the cosmos, with its floor representing Mother Earth, its roof Father Sky, and its supporting posts embodying the sacred mountains that define Dinétah, the Navajo homeland.

The structure’s most defining characteristic is its east-facing doorway. This orientation is not arbitrary; it is a deliberate act of welcoming the rising sun, symbolizing new beginnings, light, and the blessings that dawn brings. It aligns the dwelling with the natural cycle of the day and allows the first rays of sunlight to cleanse and bless the interior. Furthermore, the hogan serves as a primary site for sacred ceremonies, particularly the "House Blessing Way," which purifies and sanctifies the home, ensuring health, prosperity, and spiritual well-being for its occupants. This ceremony imbues the structure with a living spirit, solidifying its role as a sacred space.

Types of Hogans: Form Follows Function and Gender

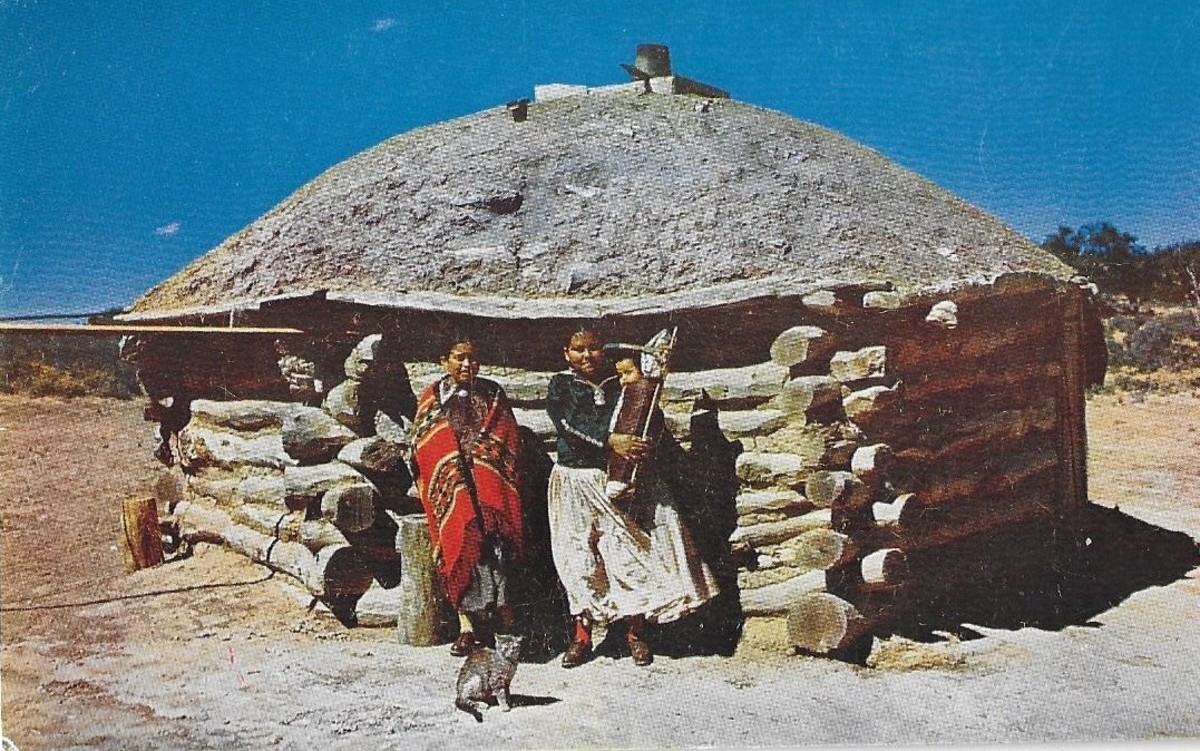

Historically, two primary forms of hogans dominated the Navajo landscape: the male or conical hogan, and the female or rounded hogan. While both share fundamental spiritual principles, their construction methods and typical uses differed.

The male hogan, also known as the "forked stick" or "conical" hogan, is the older and simpler form, tracing its origins to early nomadic or semi-nomadic life. It typically consists of three or four large logs, often juniper or piñon, interlocked at the top to form a tripod or quadrapod frame. Smaller logs are then leaned against this central frame, creating a conical shape. The entire structure is then chinked with mud and often covered with earth, providing insulation. These hogans were quicker to erect and dismantle, suitable for a more mobile lifestyle, and were traditionally used for hunting parties, temporary shelters, or ceremonial purposes. They are often associated with the concept of Father Sky, with their upward-reaching form.

The female hogan, or "round" hogan, is the more common and elaborate type, evolving as the Navajo adopted a more settled agricultural lifestyle. This dome-shaped structure, often larger and more permanent, is associated with Mother Earth, symbolizing her nurturing and encompassing embrace. Its construction involves a complex method of horizontal log placement known as "cribbing," where logs are laid in progressively smaller squares or hexagons, stacking inward to form a self-supporting dome. This method creates a more spacious and robust interior, making it ideal for family living and extended ceremonial use. The female hogan represents stability, family, and the enduring connection to the land.

In some cases, a hybrid known as the "six-sided" or "six-sided female" hogan emerged, combining aspects of both, often utilizing a hexagonal base and cribbed logs to create a more efficient and spacious structure.

The Art of Construction: A Step-by-Step Process

Building a traditional female hogan is a labor-intensive, community-driven endeavor, often involving family and neighbors, and guided by experienced builders who understand not only the physical techniques but also the spiritual protocols.

1. Site Selection and Preparation:

The process begins with careful site selection, a decision imbued with spiritual and practical considerations. Builders look for elevated ground to avoid flooding, proximity to water and timber resources, and a location that offers good views and aligns with sacred geographic features. Once chosen, the ground is cleared, and a circular or hexagonal foundation, typically 15 to 30 feet in diameter, is laid out. This outline often involves placing a ring of stones or logs, which will serve as the base for the walls.

2. Gathering Materials:

The choice of materials is dictated by local availability and traditional knowledge.

- Logs: Piñon pine, juniper, and ponderosa pine are preferred for their strength, resistance to rot, and relatively straight growth. These are typically cut and debarked to prevent insect infestation and prepare them for construction.

- Earth/Clay: A specific type of clay-rich soil is gathered for chinking, plastering, and roofing, chosen for its binding properties and insulating qualities.

- Stones: Used for the foundation and sometimes for interior hearth construction.

- Brush/Reeds: For interior insulation layers and as a base for the earth roof.

3. The Foundation and Wall Construction:

For the female hogan, a low stone wall or a ring of logs is typically laid directly on the prepared ground, forming the base of the structure. On top of this, the logs for the walls are laid horizontally in a technique known as "cribbing." Each log is carefully notched and fitted to its neighbors, creating a tight, interlocking structure. As the walls rise, each successive course of logs is laid slightly inward, gradually reducing the diameter of the opening and creating the characteristic dome shape. This inward curvature is critical for structural integrity, allowing the logs to support each other without the need for internal posts.

4. The Roof Structure:

As the walls curve inward, they eventually form a circular opening at the top, which will become the smoke hole. To complete the dome, smaller logs are carefully placed across this opening, forming a cap. In many traditional hogans, four main support posts, representing the four sacred directions, are erected internally to help support the central smoke hole frame, though the cribbing technique itself can be self-supporting. The smoke hole, usually about two feet in diameter, is left open to allow smoke from the central fire to escape and to provide ventilation.

5. Doorway and Ventilation:

The doorway is meticulously framed on the eastern side, often using two strong upright logs and a lintel. A simple wooden door, sometimes crafted from split logs or planks, is then fitted. The smoke hole, while primarily for ventilation, also serves as a spiritual portal, connecting the interior to the sky.

6. Earth Plastering and Roofing:

Once the log frame is complete, the entire exterior is covered with layers of insulating materials. First, smaller sticks, brush, or reeds are laid over the logs to create a base. On top of this, a thick layer of earth – a mixture of clay, mud, and sometimes grass or straw – is applied. This earth plaster serves multiple purposes: it seals the structure against wind and rain, provides excellent insulation against both heat and cold, and helps to stabilize the log work. Multiple layers may be applied, often dampened and packed down, to create a smooth, durable, and highly insulative exterior. "A well-built hogan is surprisingly cool in the summer and warm in the winter," is a common observation among those who have experienced them.

7. Interior Finishing:

The interior floor is typically packed earth, often smoothed and hardened. A central fire pit is dug directly beneath the smoke hole, serving as the primary source of heat and light, and a focal point for family and ceremony. Sleeping areas, storage spaces, and areas for preparing food are arranged around the perimeter. In larger hogans, specific areas are designated for men and women, reflecting traditional gender roles and spatial organization.

Evolution and Enduring Significance

While the fundamental principles of hogan construction have remained constant, adaptations have occurred over time. The introduction of Euro-American tools like saws and axes, as well as materials such as milled lumber, nails, and tarps, allowed for faster and sometimes more structurally complex builds. Some modern hogans may incorporate windows, stovepipes (replacing the open smoke hole), and even concrete foundations, yet they retain the essential circular or hexagonal form and, critically, the east-facing door.

Today, while many Navajo families reside in modern frame homes, the hogan retains its profound spiritual and cultural significance. It is still built and maintained as a primary residence by some, particularly in more remote areas. More commonly, hogans serve as ceremonial structures, places for family gatherings, or symbols of cultural identity. They are vital spaces for conducting traditional healing ceremonies, hosting rites of passage, and teaching younger generations about Diné history and values. The construction of a new hogan remains a powerful act of cultural affirmation, connecting the present generation to their ancestors and ensuring the continuity of their traditions.

The traditional Navajo hogan stands as a testament to the ingenuity, resilience, and deep spiritual connection of the Diné people. It is an architectural masterpiece born from an intimate understanding of the land, materials, and cosmos, embodying a philosophy of harmony that continues to inspire and sustain a vibrant culture. More than just shelter, the hogan is a living entity, a sacred space where the past, present, and future of the Navajo nation converge.