Echoes of the Land: The Enduring Wisdom of Turtle Island’s Traditional Ecological Knowledge

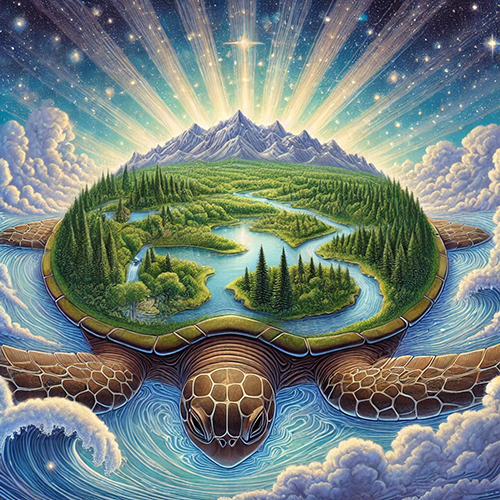

As the world grapples with unprecedented ecological crises – from accelerating climate change and biodiversity loss to the degradation of essential natural resources – a profound and urgent call is emerging from ancient sources. Across Turtle Island, the Indigenous name for what is now widely known as North America, a deep wellspring of knowledge, honed over millennia, offers not just solutions but a fundamentally different way of relating to the Earth. This is Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), a dynamic, cumulative, and intergenerational body of understanding that holds the key to forging a sustainable future.

TEK is far more than a collection of facts; it is a holistic worldview. It encompasses the intricate relationships between living beings and their environment, deeply woven with spiritual beliefs, cultural practices, language, and social structures. For Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island, the land is not merely a resource to be exploited but a living relative, a provider, and a teacher. This perspective fosters a profound sense of responsibility and reciprocity, fundamentally distinct from the dominant Western paradigm of human dominion over nature.

"For all of us, becoming indigenous to a place means living as if your children’s future mattered, to take care of the land as if your life depended on it," writes Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, a distinguished professor and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, in her seminal work Braiding Sweetgrass. This sentiment lies at the heart of TEK: an understanding that the well-being of the land is inextricably linked to the well-being of the people.

A Tapestry of Knowledge: The Pillars of TEK

The foundations of TEK are built upon generations of meticulous observation, experimentation, and adaptation. Indigenous communities, living in intimate relationship with their local ecosystems, developed sophisticated understandings of weather patterns, animal behaviors, plant cycles, soil dynamics, and water systems. This knowledge was transmitted orally through stories, ceremonies, songs, and hands-on teaching, ensuring its continuity and evolution.

One of the most striking characteristics of TEK is its emphasis on reciprocity. Unlike a system that takes without giving back, TEK teaches a cyclical relationship of mutual benefit. Harvesting plants involves leaving an offering, thanking the plant, and ensuring enough remains for future growth. Hunting animals is accompanied by prayers of gratitude and the utilization of every part, minimizing waste and honoring the life given. This ethic of gratitude and stewardship is encapsulated in the Seven Generations principle, a philosophy attributed to the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, which urges decision-makers to consider the impact of their actions seven generations into the future.

Practical Applications: Wisdom in Action

The theoretical underpinnings of TEK translate into highly effective and sustainable land management practices that are now garnering serious attention from Western scientists and policymakers.

1. Fire Management: For millennia, Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island utilized cultural burning – controlled, low-intensity fires – to manage landscapes. These intentional burns reduced fuel loads, prevented catastrophic wildfires, promoted the growth of culturally significant plants (like berry bushes and medicinal herbs), enhanced biodiversity, and created favorable conditions for game animals. When colonial policies suppressed these practices, leading to a century of fire exclusion, the result has been an accumulation of dense undergrowth and unprecedented megafires that devastate ecosystems and communities. Today, agencies like the U.S. Forest Service and Cal Fire are increasingly partnering with tribes to reintroduce traditional burning, recognizing its critical role in ecosystem health. For example, the Karuk Tribe in California has been instrumental in demonstrating how their ancestral fire practices can reduce the intensity of modern wildfires and restore forest health.

2. Sustainable Food Systems: Indigenous agricultural innovations stand as testaments to TEK’s brilliance. The Three Sisters planting method (corn, beans, and squash) of the Haudenosaunee and other Eastern Woodlands peoples is a prime example of polyculture. Corn provides a stalk for beans to climb; beans fix nitrogen in the soil, enriching it for the corn; and squash leaves shade the ground, suppressing weeds and retaining moisture. This synergistic system provides a complete nutritional profile and maintains soil fertility without external inputs. Similarly, the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) people’s sophisticated management of Manoomin (wild rice) in the Great Lakes region involves careful harvesting, reseeding, and protection of waterways, ensuring a sustainable food source for generations.

3. Medicinal Knowledge: The vast pharmacopoeia of Indigenous peoples is rooted in generations of empirical observation and spiritual understanding of plants. From pain relief and wound healing to immune boosting and mental well-being, countless medicinal plants were identified, cultivated, and prepared with precision. Many modern pharmaceuticals have their origins in Indigenous plant knowledge. For instance, the anti-inflammatory properties of willow bark, known to Indigenous healers for centuries, led to the development of aspirin.

4. Water Management: In arid regions, Indigenous communities developed ingenious systems for managing water resources. The Hohokam people of present-day Arizona constructed elaborate canal systems over a thousand years ago, diverting river water to irrigate vast agricultural fields, a feat of engineering that sustained a large population for centuries. Across the Pacific Northwest, salmon-fishing tribes developed intricate knowledge of salmon life cycles, river ecology, and sustainable harvesting techniques, ensuring the abundance of this vital protein source. Their stewardship involved maintaining healthy riverbanks, removing obstructions, and practicing selective fishing.

The Erasure and Resurgence of TEK

The arrival of European colonizers brought about a systematic assault on Indigenous cultures, languages, and land management practices. The imposition of foreign laws, the forced removal of communities from their ancestral lands, the establishment of residential schools designed to "kill the Indian in the child," and the suppression of traditional ceremonies all contributed to the fragmentation and erosion of TEK. Indigenous peoples were often denied access to their traditional territories, making it impossible to practice the land-based knowledge that defined their existence.

However, despite centuries of oppression, TEK has endured. Elders and knowledge keepers meticulously preserved these vital understandings, often in secret, passing them down through oral traditions. Today, there is a powerful resurgence. Indigenous communities are reclaiming their sovereignty, revitalizing their languages, and actively restoring traditional land management practices.

This resurgence is not just about cultural preservation; it is increasingly recognized as critical for addressing contemporary ecological challenges. Western science, often focused on reductionist approaches, is beginning to acknowledge the limitations of its own framework and the immense value of TEK’s holistic, long-term perspective. Collaborations between Indigenous knowledge holders and Western scientists are becoming more common, creating powerful synergistic approaches to conservation, climate adaptation, and resource management.

For example, Indigenous weather forecasting, based on centuries of observing nuanced environmental cues, can provide highly localized and accurate predictions, complementing satellite data and meteorological models. Similarly, Indigenous understanding of biodiversity hotspots and the interconnectedness of species offers invaluable insights for conservation efforts.

Challenges and the Path Forward

While the recognition of TEK is growing, significant challenges remain. The ongoing struggle for land rights and self-determination is paramount, as access to ancestral territories is essential for the practice and transmission of TEK. The loss of Indigenous languages, the primary vessels for much of this knowledge, continues to be a grave concern. Furthermore, there is a need to ensure that TEK is respected and honored on its own terms, rather than simply being "mined" for data by Western institutions without genuine partnership and reciprocity.

The future demands a fundamental shift in our relationship with the Earth. Traditional Ecological Knowledge from Turtle Island offers a profound blueprint for this transformation. It reminds us that we are not separate from nature but an integral part of it. It teaches us the importance of listening to the land, observing its patterns, and living with gratitude and respect. By embracing the wisdom of Indigenous peoples, not just as a historical curiosity but as a living, dynamic guide, humanity can embark on a path towards genuine sustainability, healing both the land and ourselves. The echoes of the land, carrying the wisdom of millennia, are calling, and it is time for the world to listen.