The Enduring Wisdom of Turtle Island: Unearthing Traditional Ecological Knowledge Systems

On Turtle Island, the Indigenous name for North America, a profound and intricate understanding of the natural world has been cultivated over tens of thousands of years. This Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is far more than mere environmental data; it is a holistic, dynamic, and adaptive system of spiritual, cultural, and practical wisdom acquired through direct contact with the environment, passed down through generations. It represents a living testament to humanity’s capacity for sustained, reciprocal relationship with the land, water, and all living beings. As humanity grapples with unprecedented environmental crises, the deep-seated wisdom embedded in TEK offers not just insights, but pathways to survival and sustainable coexistence.

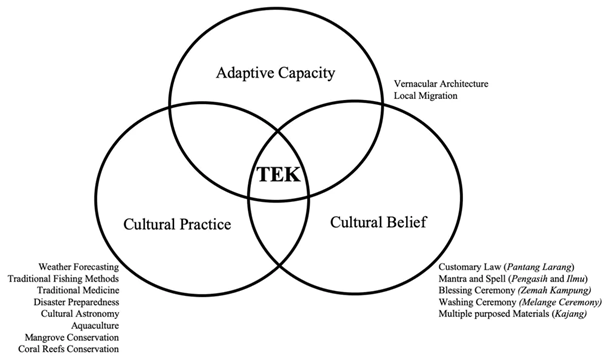

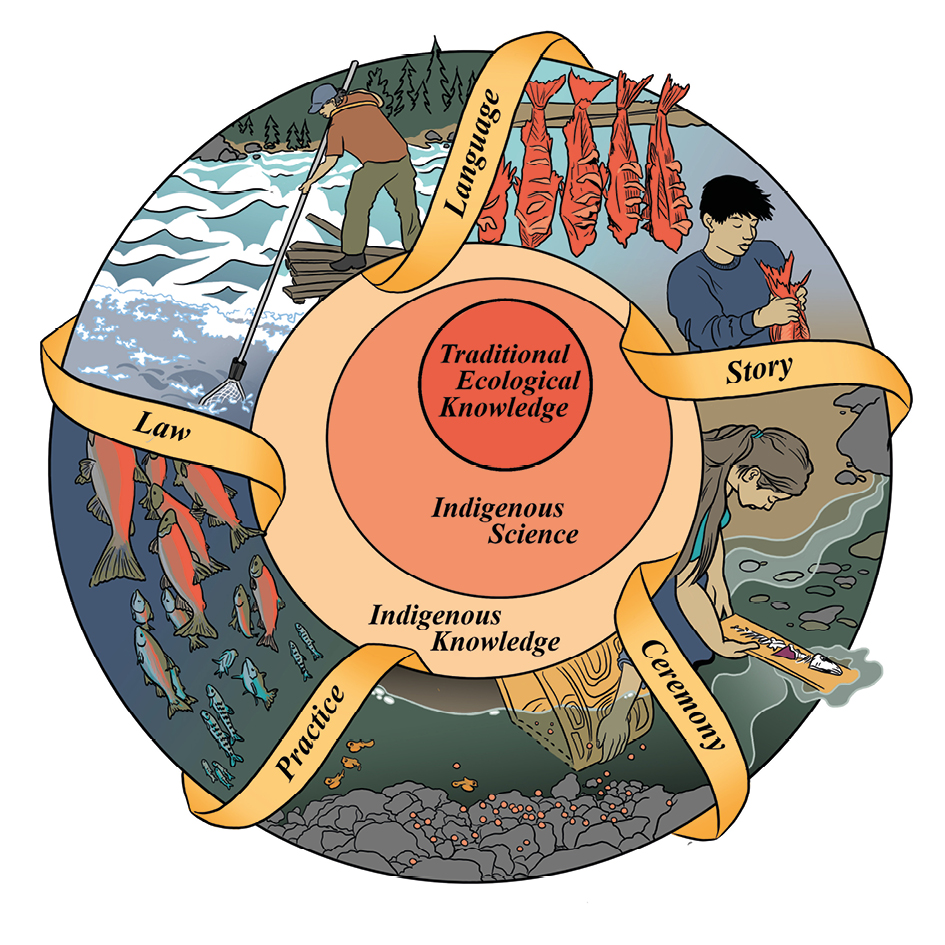

TEK is fundamentally rooted in observation, experimentation, and adaptation over vast stretches of time. It encompasses an intimate understanding of flora, fauna, soil, water, climate, and the complex interdependencies that weave them together. Unlike reductionist Western scientific approaches that often isolate variables, TEK perceives the environment as an integrated, animate system where every element is connected and possesses inherent value. This worldview fosters a deep sense of responsibility and stewardship, emphasizing not just what the land can provide, but what humans owe to the land in return. Elders, knowledge keepers, and community practices serve as living libraries, transmitting this vital information through oral histories, ceremonies, language, and direct participation in land-based activities.

One of the most compelling examples of TEK in practice is Indigenous fire management. For millennia, Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island, from the Karuk and Yurok of California to the Anishinaabe of the Great Lakes, meticulously employed prescribed burning. These controlled, low-intensity fires were not acts of destruction but sophisticated ecological tools. They cleared underbrush, prevented catastrophic wildfires, promoted the growth of culturally significant plants like berries and basketry materials, enhanced biodiversity by creating diverse habitats, and improved hunting grounds. Early European settlers, often misunderstanding these practices or viewing them as "wild," suppressed Indigenous burning, leading to fuel accumulation that now contributes to the devastating mega-fires seen across the continent. Modern fire ecologists are increasingly recognizing the invaluable role of Indigenous fire stewardship, advocating for its reintegration into contemporary land management strategies.

Beyond fire, Indigenous agricultural systems stand as powerful models of sustainability. The "Three Sisters" — corn, beans, and squash — represent a brilliant polyculture system practiced by many nations, including the Haudenosaunee, Cherokee, and many Pueblo peoples. Corn provides a stalk for beans to climb, beans fix nitrogen in the soil, and squash leaves shade the ground, suppressing weeds and retaining moisture. This symbiotic relationship enhances soil health, maximizes yield, and minimizes pest outbreaks without external inputs. Similarly, the cultivation and stewardship of Manoomin (wild rice) by Anishinaabe communities in the Great Lakes region exemplifies a respectful relationship with a vital food source. Traditional harvesting methods ensure the plant’s regeneration, demonstrating a deep understanding of its life cycle and the ecosystem it supports, contrasting sharply with industrial agricultural practices that often deplete natural resources.

Water management is another area where TEK shines. Indigenous communities developed sophisticated irrigation systems, understood aquifer dynamics, and maintained wetland ecosystems crucial for water filtration and flood control. The ancestral Pueblo people in the American Southwest, for example, engineered intricate networks of canals and check dams to manage scarce water resources for agriculture in arid environments, demonstrating an understanding of hydrology that far predated Western scientific mapping. This knowledge wasn’t just about diverting water; it was about respecting water as a sacred life-giver, a philosophy that guided sustainable use and protection.

The depth of biodiversity knowledge within TEK is equally astonishing. Indigenous languages often contain highly specific terminology for various species, their life stages, behaviors, and ecological roles, far surpassing the general classifications of common English. This granular understanding allowed for ethical harvesting practices, ensuring populations remained healthy and vibrant. For instance, the careful management of salmon populations by Pacific Northwest nations involved sophisticated understanding of spawning cycles, river health, and population dynamics, ensuring sustained harvests for millennia while maintaining the health of the entire watershed ecosystem. The concept of "ethical harvesting" is central, rooted in the belief that one takes only what is needed and gives thanks, never exploiting but always reciprocating.

However, the profound wisdom of TEK has faced immense challenges. The arrival of European colonizers initiated a systematic dismantling of Indigenous cultures, languages, and land management practices. Policies of forced assimilation, residential schools, and the imposition of foreign governance structures severed generations from their traditional lands and knowledge systems. Land dispossession, resource extraction, and the outright criminalization of Indigenous practices further eroded TEK. The dominant society often dismissed TEK as "superstition" or "primitive," preferring Western scientific paradigms, even as those paradigms led to environmental degradation. This historical trauma continues to impact Indigenous communities, manifesting in language loss, cultural disruption, and disproportionate exposure to environmental harms.

Despite these devastating impacts, TEK has shown remarkable resilience. Today, there is a powerful resurgence of Indigenous knowledge revitalization across Turtle Island. Communities are actively reclaiming languages, ceremonies, and land-based education, reconnecting youth with their ancestral heritage and ecological wisdom. Elders are working with younger generations to document and practice traditional ecological methods. Partnerships are emerging between Indigenous communities and scientific institutions, recognizing the complementary strengths of both knowledge systems. Indigenous scholars are playing a crucial role in bridging these worlds, advocating for the integration of TEK into policy-making, conservation efforts, and climate change adaptation strategies.

The relevance of TEK to contemporary global challenges cannot be overstated. As climate change accelerates, Indigenous knowledge offers invaluable insights into adapting to changing environments, understanding complex weather patterns, and developing resilient food systems. For example, traditional crop varieties often possess greater drought resistance or pest resilience than commercially developed monocultures. The holistic, long-term perspective of TEK provides a much-needed counterpoint to short-sighted, profit-driven resource management. It reminds us that environmental health is inextricably linked to social, cultural, and spiritual well-being.

Ultimately, recognizing and valuing TEK is not just about historical justice; it is about securing a sustainable future for all. It necessitates respecting Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination, empowering Indigenous communities to manage their ancestral lands according to their own knowledge systems and values. Co-management agreements, land back initiatives, and the incorporation of Indigenous voices into environmental policy are crucial steps. The wisdom cultivated over millennia on Turtle Island offers humanity a profound lesson: that true sustainability comes from a deep, reciprocal relationship with the Earth, guided by respect, responsibility, and an understanding that we are all interconnected parts of a living system. As we navigate the complexities of the Anthropocene, the enduring wisdom of Turtle Island’s Traditional Ecological Knowledge systems lights a path forward, reminding us that the answers to our most pressing environmental questions often lie in the knowledge held closest to the land.