Tonkawa Hide Tanning: Traditional Leather-Making Techniques of Texas Tribes

The vast plains and winding rivers of Texas once teemed with life, a dynamic landscape where survival was an intricate dance between humans and nature. For millennia, the Indigenous peoples of this region, including the Tonkawa, Comanche, Apache, Caddo, and Karankawa, mastered the art of living harmoniously with their environment, transforming its raw materials into essential tools, clothing, and shelter. Among their most vital skills was the intricate process of hide tanning – an ancient craft that turned the skin of animals into durable, pliable, and indispensable leather, a testament to their ingenuity, patience, and profound understanding of the natural world.

The Tonkawa, a nomadic people whose name is believed to mean "those who stay together," inhabited central Texas, following the migrating herds of bison and deer. Their survival, like many other Plains and Woodlands tribes, hinged on their ability to utilize every part of an animal. The hide, far from being a mere byproduct, was a canvas for creation, a resource transformed through a labor-intensive, often communal, process into vital components of their existence. From warm robes and sturdy moccasins to tipi coverings, water-carrying vessels, and drumheads, brain-tanned leather was the fabric of their lives.

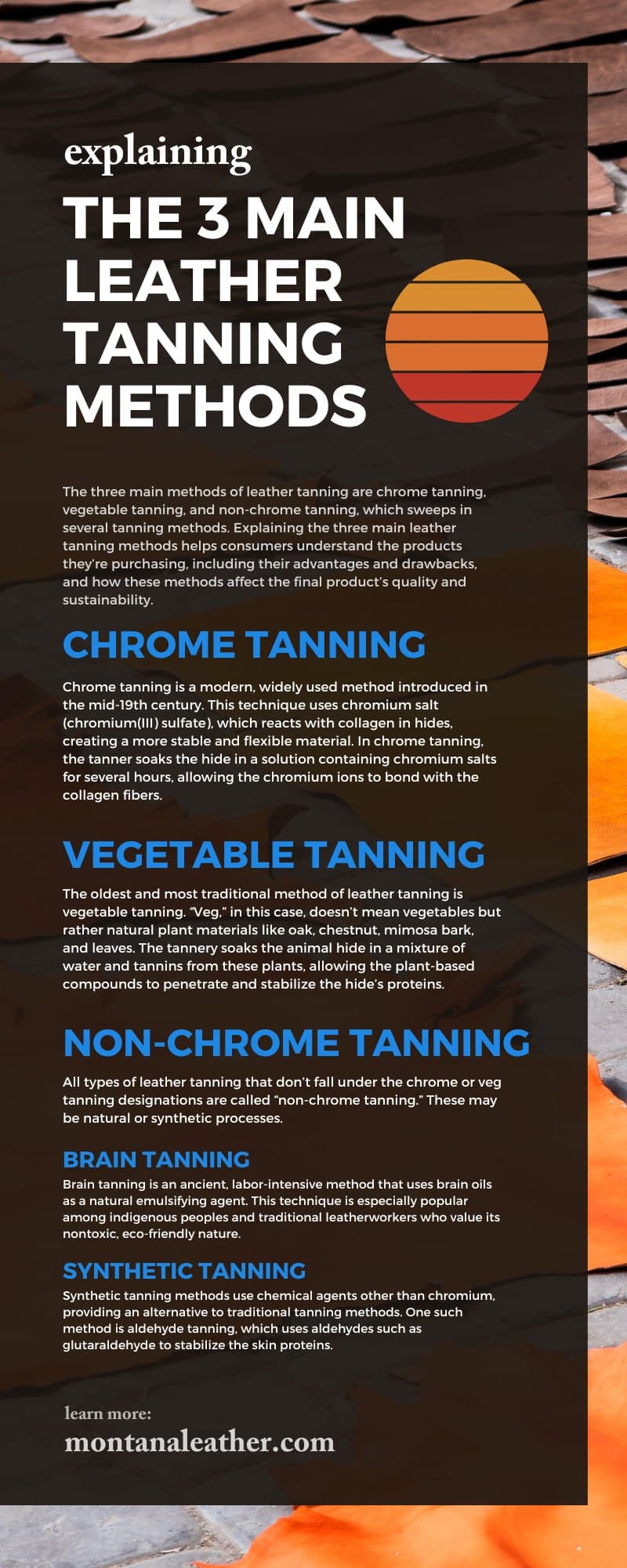

The journey from a fresh hide to soft, supple leather was not a simple one; it was a ritualistic endeavor steeped in practical knowledge and respect for the animal that provided it. This traditional method, often referred to as "brain tanning" or "buckskinning," is fundamentally different from modern chemical tanning processes. It relies on natural emulsifiers found within the animal itself, producing a leather renowned for its incredible softness, breathability, and durability, unmatched by many contemporary products.

The first critical step in this transformative process began immediately after the hunt: fleshing. The hide, still warm, was laid out, often on a sturdy log or dedicated fleshing beam. Using specialized tools, typically made from sharpened bone, stone, or later, metal blades, the tanner meticulously scraped away all remaining flesh, fat, and membrane from the inner surface. This was a physically demanding task requiring strength, precision, and a keen eye to avoid damaging the hide. Any lingering organic matter would lead to decay, rendering the hide useless. "You had to get it perfectly clean," recounts a descendant of a Texas tribal elder, emphasizing the unforgiving nature of the task. "If you left even a speck of fat, it would rot, and all your hard work would be for nothing."

Once thoroughly fleshed, the hide moved to the dehairing stage, if a hair-off buckskin was desired. For robes or winter coverings, the hair might be left on. To remove the hair, hides were often soaked in water, sometimes for several days, allowing bacterial action to loosen the hair follicles. Another method involved applying a paste made from wood ashes and water (creating an alkaline lye solution) to the hair side, which chemically loosened the hair. After soaking, the hide was again stretched over the fleshing beam, and the hair was scraped off with a duller tool, working against the grain. This step also served to remove the outer epidermal layer, exposing the underlying dermis, which would become the leather.

With the hide now clean and dehaired, it was ready for the most distinctive and crucial step: braining. Indigenous peoples discovered that the brain of an animal contains highly effective emulsified oils and fats perfectly suited for tanning its own hide. This incredible natural synergy led to the saying, "A brain tans a hide the size of the animal it came from." The brain was typically mashed into a paste, often mixed with warm water to create a slurry. This paste was then thoroughly worked into both sides of the hide, ensuring every fiber was saturated. The emulsified fats in the brain solution penetrated the hide’s fibers, coating them and preventing them from stiffening as they dried. It’s a process that essentially lubricates each individual fiber, allowing them to move independently, resulting in a soft, pliable material.

Following the braining, the hide was typically rolled up and allowed to "set" for several hours or overnight, giving the brain solution ample time to penetrate deeply. The next stage, and perhaps the most labor-intensive, was softening and stretching. This was a relentless and crucial process that determined the final suppleness of the leather. The hide was repeatedly stretched, pulled, twisted, and worked as it dried. This could involve pulling it over a rope or pole, stretching it by hand, chewing it (especially for smaller, very soft pieces), or even using specialized frames. The goal was to break down and separate the fibers that had been coated by the brain solution, preventing them from bonding together and becoming stiff. "This is where you earn your buckskin," a modern tanner might say, reflecting the immense physical effort required. If the hide dried before being fully softened, it would become stiff and board-like, requiring re-wetting and re-braining. This step was often a communal activity, with families or groups working together, sharing the labor and passing down techniques.

The final, often optional but highly recommended, step was smoking. Once the hide was perfectly soft and dry, it was suspended over a smoldering fire, usually within a makeshift tipi or tent to concentrate the smoke. Rotten wood, particularly hardwoods, was preferred as it produced a cooler, dense smoke without excessive heat. The smoke chemically alters the collagen fibers in the hide, making the leather more water-resistant, less prone to stiffening after getting wet, and imparting a beautiful, rich amber or brown color. It also acts as a natural insect repellent and gives brain-tanned buckskin its characteristic earthy aroma. This smoking process permanently "sets" the tan, ensuring the hide retains its softness. Without smoking, buckskin can revert to rawhide if it becomes thoroughly wet and dries without being worked.

The tools used in Tonkawa hide tanning were as ingenious as the process itself. Scrapers were fashioned from bison ribs, elk antlers, or flint blades hafted onto wooden handles. Sharpened stones and bone awls were used for piercing holes, and sinew, painstakingly extracted from animal tendons, served as incredibly strong thread for sewing. The entire endeavor was a testament to a deep understanding of natural physics and chemistry, developed through generations of observation, experimentation, and refinement.

Beyond its practical utility, hide tanning held profound cultural significance. It was a skill passed down from elder to youth, a tangible link to ancestral knowledge and a vital component of tribal self-sufficiency. The process fostered community, with multiple hands often needed for the laborious tasks of fleshing and softening. It instilled patience, discipline, and a deep respect for the animals that provided for them. The finished leather was not just a material; it embodied the spirit of the animal, the land, and the skilled hands that transformed it.

The arrival of European settlers and the subsequent decimation of bison herds, forced relocation, and introduction of new materials and technologies severely impacted traditional hide tanning practices among the Tonkawa and other Texas tribes. The skills, once essential for survival, gradually became less common, though never entirely forgotten.

Today, there is a vibrant resurgence of interest in traditional hide tanning. Descendants of Texas tribes, alongside enthusiasts of ancestral skills, are actively working to revive and preserve these invaluable techniques. Workshops, cultural heritage programs, and dedicated artisans are rediscovering the nuances of brain tanning, not just as a craft, but as a way to reconnect with their heritage, promote sustainable practices, and honor the wisdom of their ancestors. The Tonkawa, now primarily residing in Oklahoma, continue to uphold their cultural identity, and the echoes of their ancient tanning methods resonate through their history and in the hands of those dedicated to keeping this profound art alive.

The soft, durable buckskin produced by the Tonkawa and other Texas tribes was more than just leather; it was a symbol of resilience, resourcefulness, and a harmonious relationship with the natural world. It represented a complex body of knowledge that allowed people to thrive in challenging environments. In an era dominated by industrial production, the painstaking, natural artistry of traditional hide tanning stands as a powerful reminder of human ingenuity, the enduring strength of cultural heritage, and the timeless wisdom embedded in the land itself. It is a legacy that continues to teach us about sustainability, respect, and the profound beauty of making things with our own hands, just as the Tonkawa did for centuries on the Texas plains.