Tohono O’odham Saguaro Harvest: Sacred Desert Fruit Gathering Traditions

In the scorching embrace of the Sonoran Desert, where the saguaro cactus stands as an iconic sentinel, a centuries-old tradition unfolds each summer, deeply woven into the fabric of the Tohono O’odham Nation. This is the Bakan harvest, the gathering of the saguaro fruit, a sacred ritual that transcends mere sustenance, embodying a profound spiritual connection to the land, an ancient calendar, and the very identity of a people. Far more than a seasonal chore, the saguaro harvest is a vibrant, living testament to the enduring wisdom of the Tohono O’odham, a ceremonial invitation to the monsoon rains, and a powerful reaffirmation of their place in the desert ecosystem.

For the Tohono O’odham, whose name translates to "Desert People," the saguaro (Carnegiea gigantea) is not just a plant; it is a revered elder, a provider, and a spiritual guide. Its majestic, ribbed arms, often reaching heights of 50 feet or more, dominate the landscape, offering shelter, food, and water to countless desert creatures. But it is the fruit, appearing in late June and early July, that truly marks the turning of the year and the initiation of one of the most significant cultural events. This timing is critical, as the harvest traditionally precedes the Himdag, the monsoon season, underscoring the fruit’s role in a delicate ecological and spiritual balance.

The saguaro fruit, known as Bakan, emerges from the crown of the cactus, its vibrant red pulp a stark contrast to the desert’s muted tones. Rich in nutrients, sugars, and seeds, it has been a staple food source for the O’odham for millennia. "The saguaro is our calendar, our storehouse, our very life," explains Juanita Garcia, an elder and knowledge keeper from Sells, Arizona. "When the Bakan ripens, we know it is time. It is a signal from the Creator that the desert is ready to give, and we must be ready to receive with respect."

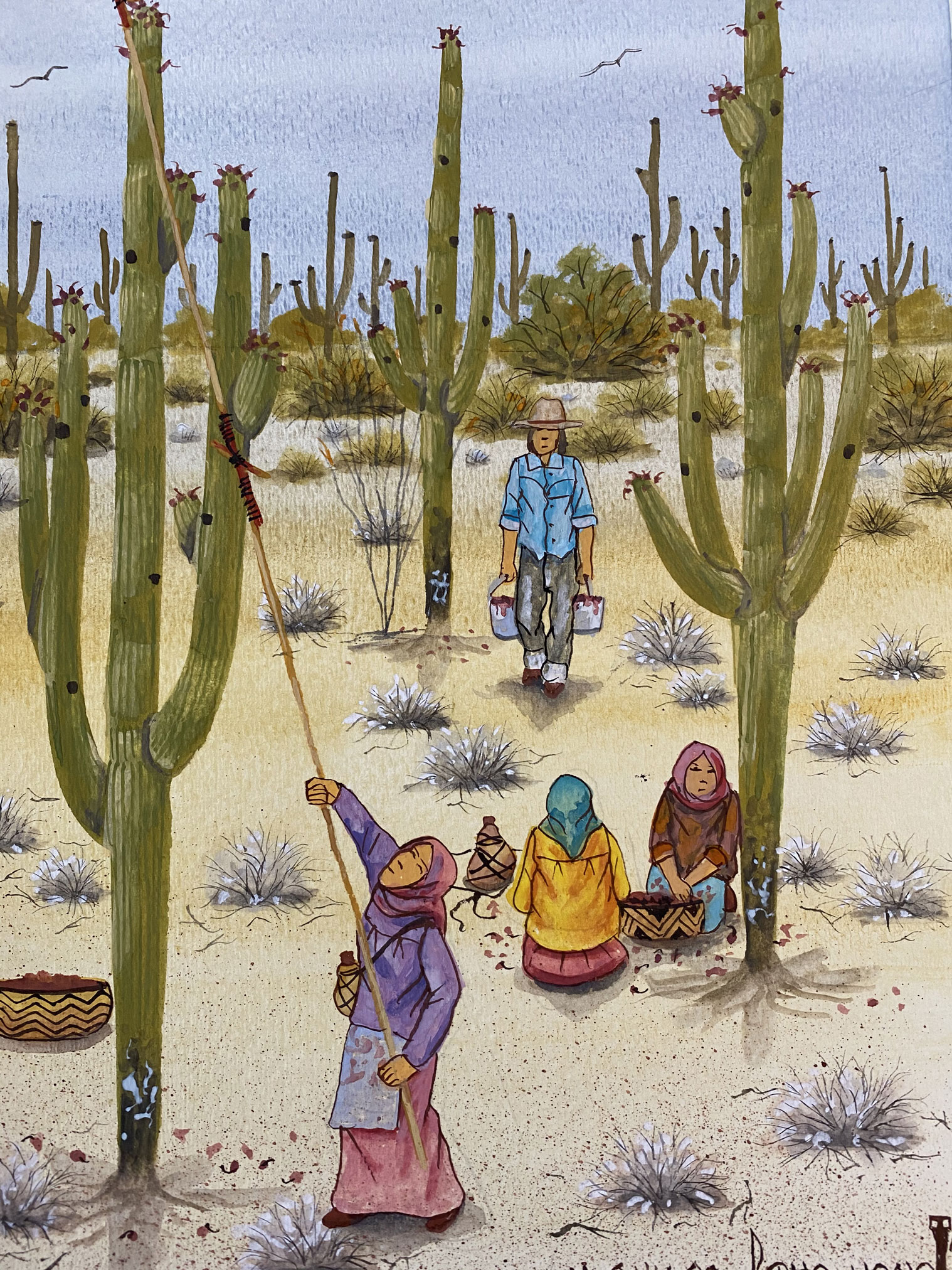

The harvest itself is a communal affair, steeped in tradition and requiring specific tools and knowledge passed down through generations. Harvesters, often families and entire communities, venture into the desert armed with a kuipad – a long, slender pole made from saguaro ribs, often topped with a smaller cross-piece or a piece of wire mesh. This ingenious tool allows them to gently dislodge the ripe fruit from the top of the towering cacti without damaging the plant or themselves. The act of gathering is a careful dance, a mindful interaction with the desert. The fruit, once fallen, is meticulously collected in buckets or traditional baskets, its bright red flesh hinting at the bounty within.

Safety and respect are paramount during the harvest. The desert heat is unforgiving, and the saguaro itself is protected by formidable spines. Harvesters must also be aware of the desert’s other inhabitants – snakes, scorpions, and other creatures that seek refuge beneath the cacti. This close interaction reinforces the O’odham understanding of interconnectedness; they are not simply taking from the desert but participating in its rhythms. The first fruits of the harvest are often offered back to the earth, a gesture of gratitude and reverence.

Once gathered, the Bakan undergoes a transformative journey. The fruit is carefully processed, typically by boiling it down to create a thick, rich syrup known as bahidaj. This dark, intensely sweet syrup is a versatile product, used to sweeten foods, make jams and jellies, and even as a medicinal tonic. The seeds, too, are valuable, dried and ground into a flour or used for their oil. Nothing is wasted, reflecting the O’odham principle of utilizing all that the desert provides.

However, the most profound transformation of the saguaro fruit occurs when it is fermented into nawait, a ceremonial wine. This wine is central to the annual Nawait I’itha, the "Wine Ceremony," a sacred ritual conducted to bring the much-needed monsoon rains. The belief is that the nawait, made from the essence of the saguaro fruit, is an offering that calls forth the clouds and nourishes the parched earth. "The saguaro gives us its fruit, we turn it into nawait, and in doing so, we help the clouds to weep," explains another elder, emphasizing the reciprocal relationship between the O’odham and their environment. The ceremony is a powerful demonstration of their spiritual worldview, where human actions and natural phenomena are intimately linked. It is a collective act of prayer, gratitude, and responsibility, acknowledging that their very survival hinges on the health of the desert and the return of the rains.

The saguaro cactus itself is a marvel of adaptation and a keystone species in the Sonoran Desert. Its long lifespan, sometimes exceeding 150-200 years, allows it to serve multiple generations of desert dwellers, human and animal alike. Its flowers provide nectar for bats and insects, its fruit feeds birds, mammals, and humans, and its sturdy trunk, once hollowed out by woodpeckers, provides nesting sites. The Tohono O’odham have observed and understood these intricate relationships for millennia, integrating this ecological knowledge into their cultural practices. Their stewardship of the land is not merely an environmental ethic but a deeply embedded way of life.

Despite the profound cultural significance and enduring traditions, the saguaro harvest faces contemporary challenges. Changing land use patterns, including urban encroachment and border militarization, can limit access to traditional harvesting grounds. Climate change, with its unpredictable weather patterns and increased drought, threatens the saguaro populations themselves, impacting fruit yield. The erosion of traditional knowledge, as younger generations move away from ancestral lands or embrace modern lifestyles, also poses a risk to the continuity of the harvest practices.

In response, the Tohono O’odham Nation and various community groups are actively working to preserve and revitalize these sacred traditions. Educational programs, cultural workshops, and intergenerational gatherings are organized to ensure that the knowledge of the kuipad, the processing of bahidaj, and the significance of the Nawait I’itha are passed on. "It is our duty to teach our children, and their children, the ways of the saguaro," states Garcia. "This is not just about food; it is about who we are, our history, our future." Efforts are also underway to monitor saguaro health, protect traditional harvesting areas, and advocate for policies that respect indigenous land rights and environmental stewardship.

The Tohono O’odham saguaro harvest is more than a cultural event; it is a living embodiment of resilience, adaptability, and profound spiritual connection. In a world increasingly disconnected from its natural roots, the sight of O’odham families gathering under the towering saguaros, their kuipads reaching for the sky, offers a powerful lesson. It is a reminder that true wealth lies not in material possessions, but in the wisdom of the elders, the bounty of the land, and the enduring strength of community. The Bakan harvest, with its crimson fruit and sacred ceremonies, continues to nourish not only the bodies but also the souls of the Tohono O’odham, ensuring that their desert traditions will thrive for generations to come, calling forth the rains and reaffirming their identity under the vast Sonoran sky.