Echoes in the Saguaro: The Enduring History of the Tohono O’odham in the Sonoran Desert

The Sonoran Desert, a landscape of stark beauty and formidable challenges, is more than just a biome; it is a cradle of civilization, a living museum of human ingenuity and resilience. For millennia, this vast, sun-baked expanse, stretching across what is now southern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico, has been home to the Tohono O’odham, the "Desert People." Their history is not merely a chronicle of survival in an unforgiving environment, but a testament to a profound spiritual and practical connection to their homeland, a narrative woven into the very fabric of the saguaro, mesquite, and creosote bush.

The story of the Tohono O’odham begins long before recorded history, rooted in the traditions of their ancestors, often linked culturally to the ancient Hohokam people who engineered sophisticated irrigation systems in the region. While direct lineage is debated, the O’odham share a deep understanding of water management, desert agriculture, and a reverence for the land that echoes through the ages. For countless generations, the O’odham developed a sustainable way of life, guided by what they call "Himdag" – their way of life, their cultural values, their worldview. It encompasses their language, ceremonies, oral histories, and their intimate knowledge of the desert ecosystem.

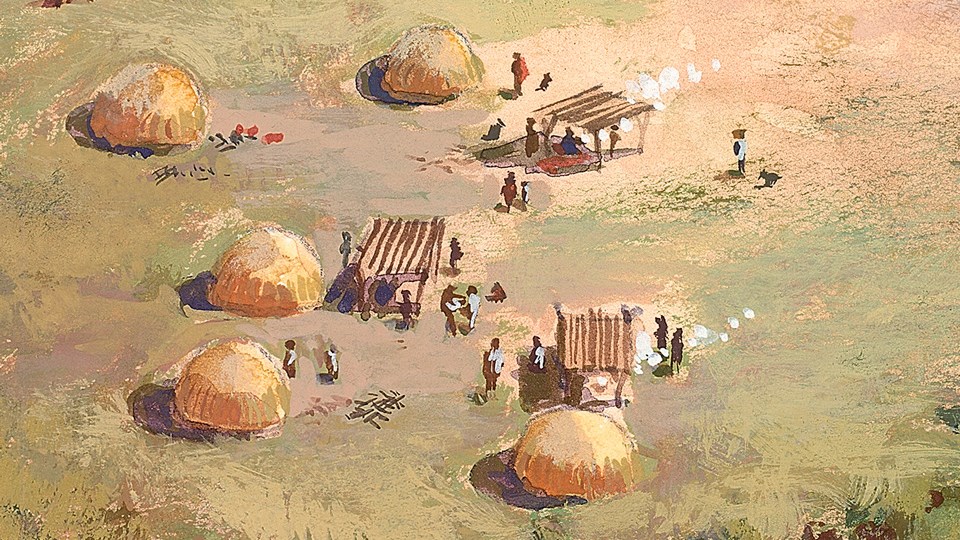

Their traditional economy was a masterful blend of hunting, gathering, and sophisticated dry-land farming. They cultivated corn, beans, and squash, utilizing ingenious techniques to capture and conserve precious rainwater runoff. The desert itself was their grocery store, pharmacy, and hardware store. The saguaro cactus, an iconic symbol of the Sonoran, was central to their existence. Its fruits, harvested with long poles in late summer, provided a vital source of food, syrup, and wine, marking a significant ceremonial period. "The saguaro is our mother," an elder might say, emphasizing its nurturing role. Mesquite pods were ground into flour, cholla buds were roasted, and countless other plants provided sustenance and medicine. Their homes, called "ki," were built from adobe, brush, and saguaro ribs, perfectly adapted to the desert climate.

The relative isolation and self-sufficiency of the Tohono O’odham ended dramatically with the arrival of Europeans. In the late 17th century, Spanish missionaries, most notably Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino, ventured into O’odham lands. While Kino introduced new crops, livestock like cattle and horses, and a different spiritual path, his arrival also heralded immense disruption. European diseases, against which the O’odham had no immunity, decimated their populations. The imposition of mission life, with its demands for labor and religious conversion, began to erode traditional practices and social structures. Yet, even under Spanish and later Mexican rule, the O’odham maintained much of their cultural identity, often adopting elements that served their needs while preserving their core Himdag.

The mid-19th century brought perhaps the most profound rupture in O’odham history: the imposition of an international border. The Gadsden Purchase of 1853, an agreement between the United States and Mexico, drew an arbitrary line across the Sonoran Desert, carving through ancestral O’odham lands and dividing families, communities, and sacred sites. Overnight, a unified people became "Americans" and "Mexicans," subject to different laws and governments, their freedom of movement severely curtailed. This act, decided by distant powers, remains a deep wound in the O’odham consciousness. As a common refrain states, "We did not cross the border; the border crossed us."

The establishment of the United States reservation system further confined the Tohono O’odham. While intended to provide a land base, it often meant relocation to less desirable areas, the loss of vast tracts of traditional territory, and increased dependence on the U.S. government. The reservation period was marked by attempts at forced assimilation, including the notorious boarding schools where O’odham children were taken from their families, forbidden to speak their language, and stripped of their traditional clothing and customs. The goal was to "kill the Indian to save the man," a policy that inflicted intergenerational trauma but failed to extinguish the O’odham spirit.

Despite these immense pressures, the Tohono O’odham persisted. Their resilience is a defining characteristic. They found ways to adapt, to resist, and to preserve their culture in the face of overwhelming odds. The mid-20th century saw a resurgence of self-determination. The Tohono O’odham Nation formally established its tribal government, asserted its sovereignty, and began to reclaim control over its destiny. This period marked the beginning of efforts to develop their economy, improve infrastructure, and address the myriad social and economic challenges stemming from centuries of oppression.

One of the most critical battles for the Tohono O’odham has been the fight for water rights. In a desert environment, water is life, and the diversion of rivers like the Gila for non-Native agriculture and urban development severely impacted O’odham communities. After decades of advocacy, the Tohono O’odham Nation achieved a landmark victory with the Central Arizona Water Settlement Act of 2004, which allocated a substantial amount of Colorado River water to the Nation. This agreement, while complex, represented a significant step towards economic stability and cultural revitalization, allowing for the expansion of agriculture and the establishment of new enterprises.

Today, the Tohono O’odham Nation is a vibrant, self-governing entity with a population of over 28,000 members residing on reservations spanning over 2.8 million acres, making it the second-largest Native American land base in Arizona. The Nation operates its own police force, judicial system, schools, and healthcare facilities. Economic development includes casinos, agricultural ventures, and tourism, providing jobs and resources for the community. However, the legacy of historical injustices continues to pose challenges, including issues of poverty, healthcare disparities, and the ongoing struggle to preserve their language and cultural practices among younger generations.

The enduring division of their ancestral lands by the U.S.-Mexico border remains a deeply felt contemporary issue. The construction of a border wall has further complicated life for O’odham families, making it harder to visit relatives, access traditional lands, and perform ceremonies. The wall cuts through sacred sites, disrupts wildlife migration, and symbolizes a continued disrespect for O’odham sovereignty and their inherent connection to the entire Sonoran Desert. Tribal leaders frequently speak out against the wall, emphasizing that the O’odham have always been the stewards of this land, long before any national boundary was conceived.

The history of the Tohono O’odham is a powerful narrative of endurance, adaptation, and an unwavering connection to their ancestral lands. From their ancient origins as master desert dwellers to their encounters with foreign powers, through periods of immense hardship and cultural assault, they have maintained their Himdag. Their story is a vital part of the American mosaic, a reminder of the deep roots of indigenous peoples and the ongoing struggle for self-determination and justice. As the saguaro stands tall and resilient against the desert sun, so too do the Tohono O’odham, their voices echoing across the timeless landscape of the Sonoran Desert, reminding us of a heritage that refuses to be silenced.