The Slow Extinction: Turtle Island’s Freshwater Guardians Face a Cascade of Crises

Across the vast and ancient lands known by many Indigenous peoples as Turtle Island – encompassing what is now North America – a silent crisis is unfolding beneath the surface of rivers, lakes, and wetlands. Freshwater turtles, ancient mariners whose lineage predates the dinosaurs, are facing an unprecedented onslaught of threats that imperil their very existence. These stoic reptiles, integral to the ecological balance and deeply revered in many Indigenous cultures, are disappearing at an alarming rate, their slow, deliberate lives no match for the rapid pace of human-induced change. Their plight is a stark indicator of the declining health of aquatic ecosystems, signaling a broader environmental collapse that demands urgent attention.

The primary driver of this decline is habitat loss and degradation. From the sprawling urban centers along the Great Lakes to the agricultural expanses of the Mississippi River basin, wetlands are drained, rivers are dammed, and shorelines are developed at an unsustainable pace. Turtles, particularly species like the Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) with its distinctive yellow throat, require pristine, interconnected habitats. They need open water for foraging, basking logs for thermoregulation, soft soil for nesting, and adjacent wetlands for overwintering. When these critical components are fragmented or destroyed, their populations become isolated and unsustainable.

"Every lost wetland, every channelized stream, is a nail in the coffin for these species," emphasizes Dr. Anya Sharma, a leading herpetologist at the University of the Great Lakes, whose research focuses on freshwater turtle conservation. "They need intact, interconnected habitats to survive, breed, and migrate. When we build a shopping mall on a marsh or straighten a meandering river, we’re not just losing a piece of land; we’re severing the life support system for countless creatures, including turtles." Dams, in particular, pose a colossal threat, transforming free-flowing rivers into reservoirs, altering thermal regimes, blocking migratory routes, and often drowning critical nesting or basking sites.

Pollution further poisons the waters these ancient reptiles call home. Agricultural runoff introduces pesticides, herbicides, and excessive nutrients, leading to algal blooms that deplete oxygen and alter aquatic plant communities. Industrial discharge releases heavy metals and toxic chemicals, accumulating in the turtles’ tissues and disrupting their physiological functions. Perhaps most insidious is the pervasive spread of plastics, from microplastics ingested by filter-feeding species to larger debris that can cause entanglement, internal blockages, and starvation. A study published in Environmental Toxicology found microplastic particles in the digestive tracts of common snapping turtles across several North American waterways, raising concerns about long-term health impacts.

Climate change adds another layer of existential threat. Freshwater turtles are particularly vulnerable due to their reliance on specific thermal conditions for incubation and their unique reproductive strategy known as Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination (TSD). For many species, warmer nest temperatures produce females, while cooler temperatures produce males. As global temperatures rise, increasing nest temperatures could skew sex ratios dramatically, potentially leading to populations composed almost entirely of females, rendering them reproductively inviable in the long term.

"Imagine a future where a species like the snapping turtle, a symbol of resilience, finds its very future jeopardized by altered sex ratios, with warming nests producing disproportionately female hatchlings year after year," warns Dr. Leo Chen, a climate biologist specializing in reptile ecology. "This isn’t a distant threat; it’s happening now, compounding the pressure from habitat loss and pollution." Beyond TSD, climate change brings more frequent and intense droughts, reducing water levels and concentrating pollutants, and more severe floods, which can wash away nests and hatchlings, and displace turtles from their established territories.

The shadowy world of the illegal wildlife trade and poaching presents an immediate and devastating threat. The allure of rare species for the black market pet trade, or for traditional medicine markets overseas, has fueled a devastating surge in poaching. North American freshwater turtles, especially those with unique patterns or long lifespans like the Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) or Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata), fetch high prices. Poachers often target nesting females, effectively wiping out an entire generation’s reproductive potential. The slow reproductive rate of turtles – they often take many years to reach sexual maturity and lay relatively few eggs – means that populations cannot quickly recover from such intense pressures.

"We’ve seen organized crime rings targeting specific species, moving hundreds, sometimes thousands, of turtles across borders," states an anonymous wildlife enforcement officer, who has worked multiple cases involving turtle smuggling. "These aren’t just isolated incidents; it’s a multi-million dollar industry that thrives on the rarity of these animals, pushing them closer to extinction with every capture."

Invasive species also contribute to the decline. Non-native predators like raccoons and feral hogs, whose populations are often bolstered by human-altered landscapes, raid turtle nests with devastating efficiency. The ubiquitous Red-Eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), often released into the wild by pet owners, competes with native species for food, basking sites, and breeding opportunities, and can also introduce diseases. Disease itself, often exacerbated by environmental stress, is an emerging threat. Viruses, bacteria, and parasites can decimate populations, particularly when turtles are concentrated in shrinking habitats.

Furthermore, the expansion of human infrastructure leads to direct mortality through road mortality. Female turtles, driven by instinct to find suitable nesting sites, often cross roads, becoming vulnerable to vehicle strikes. Their slow movement, low profile, and hard shell offer little defense against speeding cars. Conservation efforts frequently involve building culverts or fencing along roads to guide turtles safely, but these interventions are often localized and insufficient for the scale of the problem.

For countless generations, Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island have lived in profound reciprocity with these creatures, regarding them as sacred teachers and guardians of water. The turtle, often depicted as carrying the world on its back, symbolizes creation, wisdom, and longevity. The current crisis is not just an ecological one; it is a cultural and spiritual loss. "The health of the turtle reflects the health of our waters, and the health of our waters reflects the health of our people. We are all connected," reminds Elder Josephine Rivers of the Anishinaabe Nation, whose traditional territories span parts of the Great Lakes region. "When the turtles suffer, we all suffer."

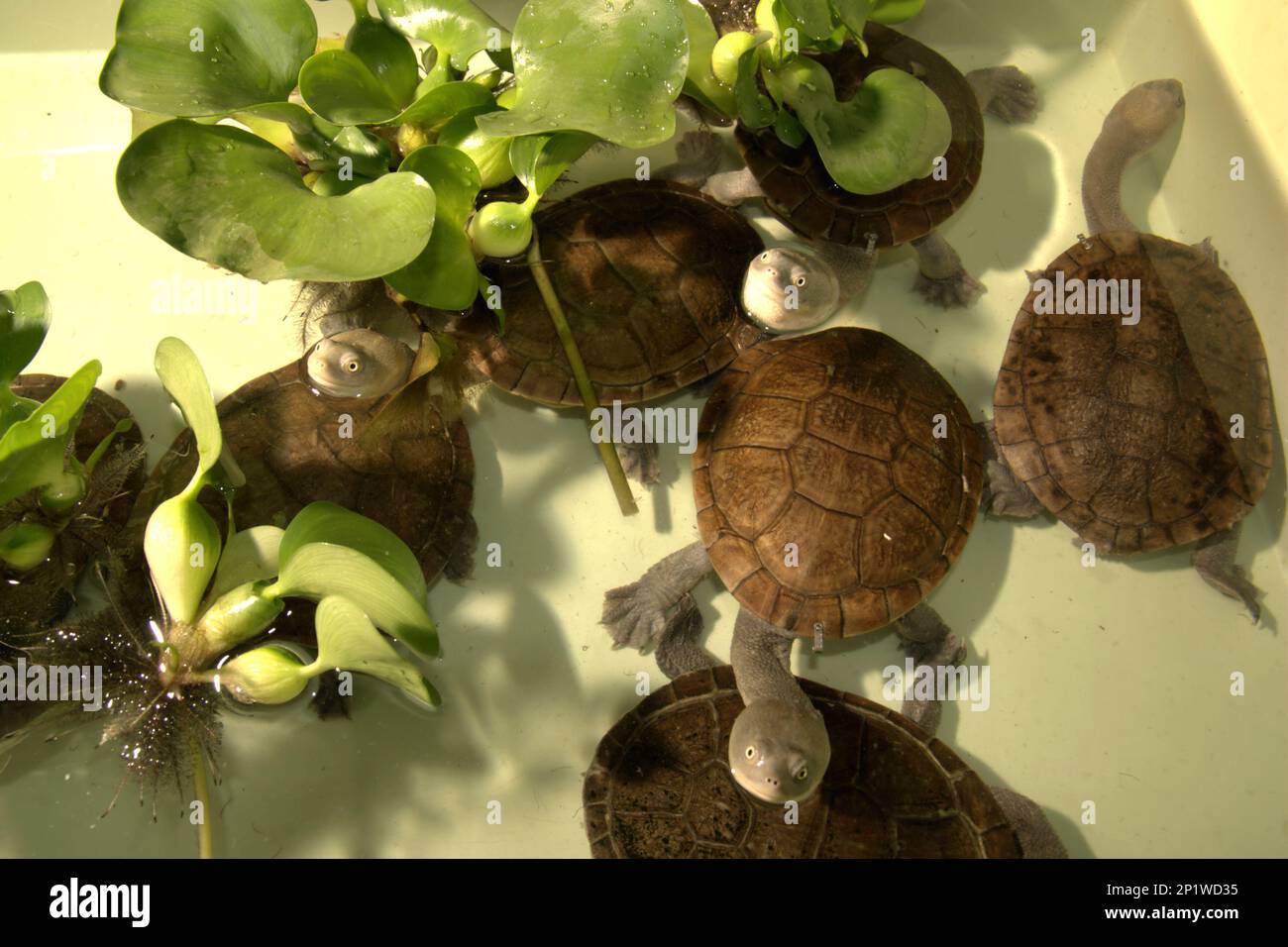

Despite the grim outlook, dedicated individuals and organizations are fighting tirelessly to reverse these trends. Conservation efforts range from hands-on approaches like "head-starting" programs, where eggs are collected, incubated, and hatchlings raised in captivity until they are large enough to avoid most predators, to large-scale habitat restoration projects. Wetlands are being re-created, dam removal projects are restoring river connectivity, and land acquisitions are protecting critical habitats. Legislation, both national and international, aims to combat the illegal wildlife trade, though enforcement remains a significant challenge.

Community engagement and education are vital, raising public awareness about the importance of turtles and simple actions like watching out for turtles on roads, reporting suspicious activity, and never releasing pet turtles into the wild. Indigenous communities are often at the forefront of these efforts, integrating traditional ecological knowledge with modern science to develop holistic conservation strategies. Their deep understanding of the land and its creatures offers invaluable insights into sustainable practices.

The plight of Turtle Island’s freshwater turtles is a stark reminder of our own ecological interconnectedness. These ancient, slow-moving sentinels of our aquatic ecosystems are sounding an alarm. Their continued survival depends not just on scientific intervention, but on a fundamental shift in human values – a recognition of our shared destiny with all life on this planet. The choice is clear: allow these resilient guardians to fade into extinction, or commit to being responsible stewards of the lands and waters they have called home for millions of years. The fate of Turtle Island’s freshwater turtles is, in essence, a reflection of our own future.