The Real Wampanoag Thanksgiving Story: History Beyond the Colonial Narrative

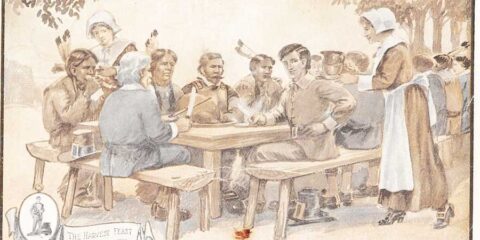

The image is etched into the American consciousness: Pilgrims and Native Americans, sharing a bountiful feast, symbols of harmonious coexistence and mutual gratitude. This picturesque scene, taught in schools and celebrated annually, forms the bedrock of the Thanksgiving narrative. Yet, for the Wampanoag people, whose ancestral lands encompassed what is now southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island, this story is a profound misrepresentation, a convenient fiction that obscures centuries of sophisticated civilization, devastating loss, and enduring resilience. To truly understand Thanksgiving, one must look beyond the colonial lens and embrace the complex, often painful, history of the Wampanoag.

Before the Mayflower ever sighted Cape Cod in 1620, the Wampanoag Nation was a thriving, politically sophisticated confederation of over 69 villages, numbering an estimated 50,000 people. Their society was deeply intertwined with the land and sea, practicing sustainable agriculture, sophisticated hunting, and extensive fishing. They cultivated corn, beans, and squash – the "Three Sisters" – and managed forests through controlled burns to promote game and clear underbrush. Their spiritual beliefs were holistic, centered on a profound respect for the natural world and a reciprocal relationship with all living things. They were not a primitive people waiting to be "discovered" but a highly organized, self-sufficient civilization with a rich oral tradition, intricate social structures, and established trade networks stretching across the continent. Their knowledge of the land, its cycles, and its resources was unparalleled, a wisdom honed over 12,000 years of continuous habitation.

However, the arrival of Europeans long before the Pilgrims brought an invisible, catastrophic enemy: disease. Between 1616 and 1619, a series of epidemics, likely leptospirosis or bubonic plague brought by European traders and explorers, ravaged the Wampanoag. Whole villages were wiped out, with some estimates suggesting a mortality rate as high as 75-90%. This "Great Dying" left the Wampanoag Nation severely weakened, their social fabric frayed, and their ability to defend their territory compromised. It was into this landscape of profound grief and demographic collapse that the English Separatists, the Pilgrims, stumbled.

When the Mayflower dropped anchor in Patuxet (renamed Plymouth by the Pilgrims) in December 1620, they landed in a ghost town. Patuxet was one of the villages devastated by the plague, its fields lying fallow, its inhabitants gone. The Pilgrims, ill-equipped and struggling to survive their first harsh winter, unknowingly occupied land that had once belonged to the Wampanoag. Their survival was far from guaranteed; half of their original 102 passengers died that winter.

The pivotal figure in the actual events of 1621 was not a friendly, benevolent "Squanto" but Tisquantum, a man whose life story encapsulates the brutal realities of early colonial encounters. Tisquantum was a Patuxet Wampanoag who, in 1614, was kidnapped by English slave traders and taken to Europe. He learned English while enslaved in Spain and later in England, eventually making his way back to his homeland in 1619, only to find his entire village wiped out by the plague. His unique position as a survivor, a polyglot, and a man deeply familiar with both Wampanoag culture and European ways made him invaluable – and deeply conflicted.

Tisquantum’s role was not one of simple friendship. He served as an interpreter and intermediary between the Wampanoag sachem (leader), Ousamequin (known to the English as Massasoit), and the struggling Pilgrims. Ousamequin, acutely aware of his nation’s diminished strength and surrounded by powerful rival tribes like the Narragansett, saw a strategic opportunity in an alliance with the English. The Pilgrims possessed firearms, a technology the Wampanoag sought to counter their enemies. In March 1621, Ousamequin and Governor John Carver signed a peace treaty, a mutual defense pact aimed at securing the Wampanoag’s regional power and providing the Pilgrims with a crucial ally and guide in their new, unforgiving environment.

The "first Thanksgiving" in the autumn of 1621 was not a pre-planned feast of cross-cultural amity. It was, more accurately, a diplomatic gathering and a harvest celebration. The Pilgrims, having brought in their first successful harvest, fired their guns in celebration. Ousamequin, hearing the commotion and likely believing it signaled a conflict, arrived with 90 of his warriors, prepared for battle. Upon realizing it was a celebration, they stayed for three days, contributing five deer to the Pilgrims’ meager fare of wild fowl and perhaps some shellfish and vegetables. This event was a practical necessity, a reaffirmation of the treaty, and a strategic maneuver for both parties, not a spontaneous expression of gratitude and friendship. The Wampanoag had their own traditional harvest festivals, Nickommo, which were far more elaborate and meaningful to their culture than this hastily arranged gathering.

The idyllic image of the 1621 feast quickly dissolved into a grim reality for the Wampanoag. The alliance, initially beneficial, rapidly soured as more English settlers arrived, driven by land hunger and religious fervor. The English saw the land not as a shared resource but as property to be owned, fenced, and "improved." Their ever-expanding settlements encroached upon Wampanoag hunting grounds, fishing weirs, and sacred sites. They introduced new concepts of law and governance that undermined Wampanoag sovereignty, pushing the indigenous people to convert to Christianity and adopt English customs.

Within a generation, the balance of power shifted dramatically. By the 1670s, the Wampanoag and other New England tribes were under immense pressure, their lands dwindling, their way of life threatened. This escalating tension culminated in King Philip’s War (1675-1676), named by the English after Ousamequin’s son, Metacom (whom they called Philip). This brutal conflict, one of the deadliest in American history in proportion to the population, saw indigenous towns razed, crops destroyed, and thousands of Native Americans killed or enslaved. Metacom himself was killed, his head displayed on a pike in Plymouth for two decades. The war effectively broke the power of the Wampanoag and their allies, paving the way for unchecked colonial expansion.

The legacy of this period for the Wampanoag was catastrophic: massive loss of life, land, language, and cultural practices. Many survivors were forced into servitude, relocated to "praying towns" where their culture was systematically suppressed, or fled to other regions. For centuries, the Wampanoag struggled for survival, their history marginalized, their contributions erased, and their very existence denied.

Yet, the Wampanoag endured. Their spirit of resilience, passed down through generations, refused to be extinguished. In 1970, on the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ landing, Frank James, a Wampanoag leader, was invited to speak at a celebratory banquet. He intended to deliver a speech that would expose the true history of his people, but his words were deemed "too inflammatory" by the organizers. Instead of reading the censored version, James refused to speak and, along with other Wampanoag and Native American activists, established the National Day of Mourning. This annual event, held on Cole’s Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts, on the same day as Thanksgiving, serves as a powerful counter-narrative, a testament to indigenous survival, and a reminder of the genocide and oppression that followed the arrival of Europeans. It is a day to reflect on the devastation, to honor ancestors, and to affirm the enduring vitality of indigenous cultures.

Today, the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) are federally recognized tribes, actively engaged in revitalizing their language, preserving their cultural heritage, and reclaiming their sovereignty. They continue to fight for land rights, for environmental protection, and for accurate representation of their history. Their efforts are not about erasing the Pilgrims from history but about integrating the Wampanoag story into the national narrative, recognizing it as an indispensable part of American history.

The "real" Wampanoag Thanksgiving story is not one of simple harmony. It is a story of a sophisticated civilization encountering an alien culture, of strategic alliances forged in desperation, of devastating disease, broken treaties, brutal warfare, and centuries of oppression. It is also a story of extraordinary resilience, cultural survival, and an unwavering commitment to truth. By acknowledging this deeper history, Americans can move beyond a simplistic, colonial-centric myth and embrace a more honest, inclusive understanding of their past – one that truly honors all those who walked this land. Only then can we begin to understand what true gratitude and reconciliation might entail.