The Powhatan Confederacy: A Masterclass in Eastern Woodlands Political Organization

In the annals of early American history, the Powhatan Confederacy stands as a testament to sophisticated indigenous political organization, a formidable power encountered by the first English colonists in Virginia. Far from a loose collection of tribes, this was a meticulously structured political entity, a true empire forged through conquest, diplomacy, and strategic alliances, presided over by the visionary paramount chief, Wahunsenacawh, commonly known as Powhatan. Its complex system of governance, economic control, and military might was a direct challenge to European notions of "primitive" societies and remains a compelling study in Native American ingenuity.

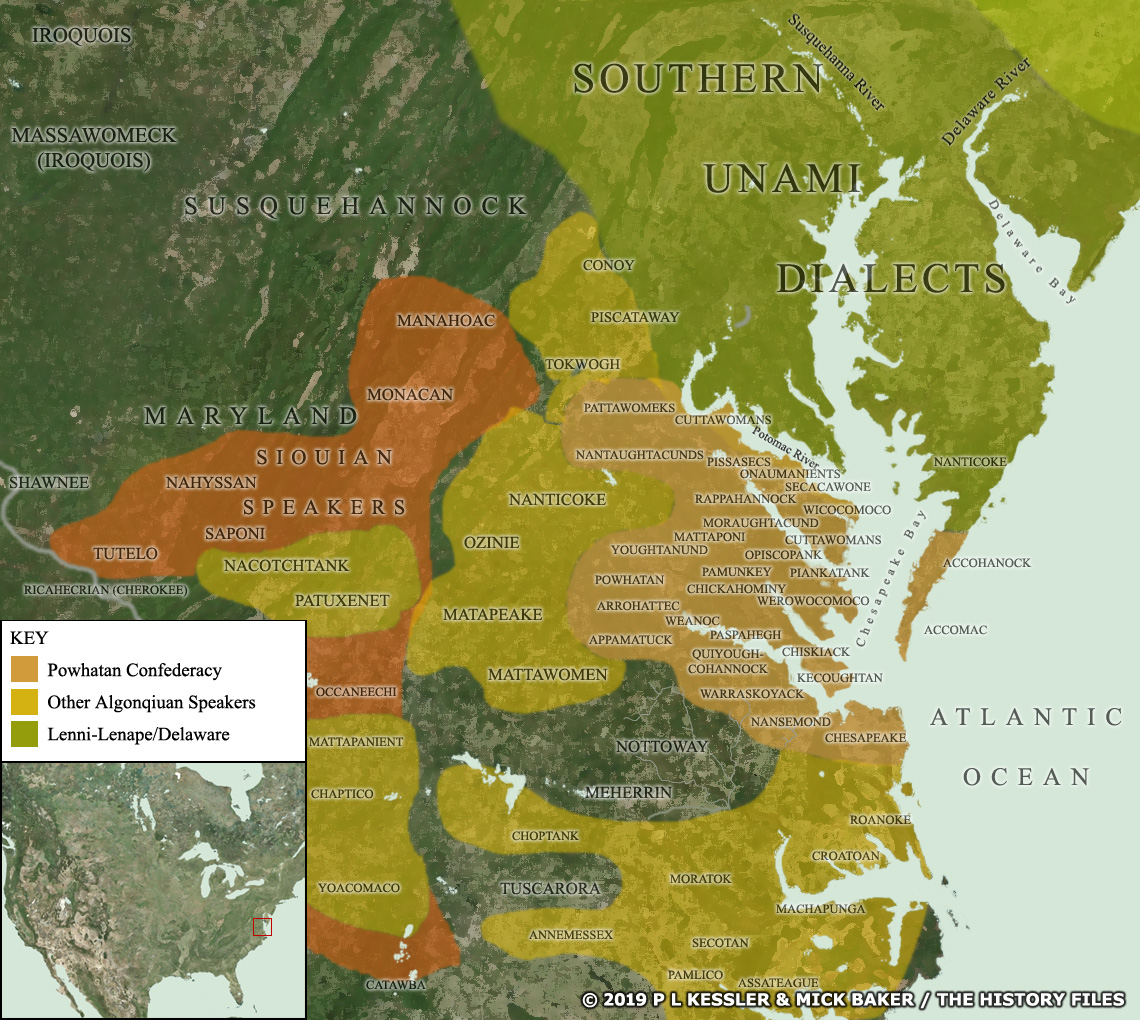

When the English ships landed at Jamestown in 1607, they did not stumble upon an untamed wilderness, but into the heart of an already established and thriving political landscape. The Powhatan Confederacy, at its zenith, comprised an estimated 30 distinct quiakohannocks (towns or districts), controlling a vast territory stretching from the southern banks of the Potomac River to the Great Dismal Swamp, and from the fall line of the rivers to the Chesapeake Bay. This domain was home to roughly 15,000 to 20,000 people, united under a single, powerful leader.

The Architect: Wahunsenacawh, The Unifier

At the apex of this elaborate structure was Wahunsenacawh, a figure of immense political acumen and military prowess. His personal name, "Powhatan," also designated his primary town and, by extension, the entire confederacy, signifying his integral role in its creation. Wahunsenacawh inherited control over six core tribes in the Tidewater region of Virginia around 1570. Over the next three decades, through a combination of strategic warfare, political maneuvering, and astute diplomacy, he systematically expanded his influence, coercing or absorbing neighboring groups into his nascent empire.

His methods were effective: recalcitrant towns faced military subjugation, their leaders either replaced by loyalists or compelled to swear allegiance and pay tribute. Others were drawn in through more peaceful means, often through strategic marriages between Wahunsenacawh’s many daughters and the weroances (sub-chiefs) of allied or conquered territories. This intricate web of kinship and obligation cemented loyalty and provided a crucial framework for governance. Wahunsenacawh’s vision was clear: to consolidate power, maintain peace (or at least controlled conflict) within his domain, and present a unified front against external threats, whether from rival indigenous groups or, later, the encroaching English.

A Hierarchical System: The Layers of Power

The political organization of the Powhatan Confederacy was remarkably hierarchical, a sophisticated model that belied simplistic European interpretations.

At the very top was the Mamanatowick, the paramount chief, a position held by Wahunsenacawh. His authority was extensive, encompassing control over tribute, military command, diplomatic relations, and ultimate judicial review. While he ruled with considerable power, his decisions were often informed by councils of elders and wise men, ensuring a degree of consensus and legitimacy. His court, centered at Werowocomoco (and later Orapax and Matchut), was the administrative hub, where tribute was collected, redistributed, and major decisions were made.

Beneath the Mamanatowick were the Weroances (men) and Weroansquas (women), the district or town chiefs. These individuals governed the individual quiakohannocks that comprised the confederacy. Their positions were often hereditary, typically passed down matrilineally, meaning succession went through the female line (e.g., from a chief to his sister’s son). Each weroance was responsible for the day-to-day administration of their territory, including local justice, leading their own war parties, and collecting local tribute.

Crucially, the weroances were not independent rulers but vassals of Wahunsenacawh. Their loyalty was maintained through a delicate balance of coercion and reward. They were expected to pay regular tribute to the paramount chief, provide warriors when called upon, and adhere to his directives. Failure to comply could result in severe consequences, including military intervention and the replacement of the weroance. John Smith, an early English observer, noted that the Confederacy was "a Kingdome divided into many pettie Kingdomes, and every one hath their owne particular King" (weroance), highlighting the semi-autonomous but ultimately subordinate nature of these local leaders.

Further down the hierarchy were the common people – farmers, hunters, artisans – who constituted the base of this pyramid. They owed allegiance and labor to their weroance, who in turn owed it to Wahunsenacawh.

Economic Foundation: Tribute and Redistribution

The political cohesion of the Powhatan Confederacy was undergirded by a robust economic system centered on tribute and controlled trade. Wahunsenacawh’s power was directly linked to his ability to demand and redistribute resources.

Tribute was a cornerstone of this system. Subordinate quiakohannocks were required to provide a regular supply of goods, primarily corn, beans, and squash (the "three sisters" of Native American agriculture), but also furs, deerskins, copper, pearls, and other valuable commodities. This tribute served multiple purposes: it fed Wahunsenacawh’s court, supported his elite warriors, provided a strategic reserve against famine, and allowed for the redistribution of wealth, which in turn fostered loyalty and dependency. Control over food resources was a potent tool, ensuring that no single weroance could starve out the paramount chief.

Trade, particularly in coveted materials like copper, was also tightly controlled by Wahunsenacawh. Copper was not only used for ornamentation and tools but was also a significant symbol of status and power. By monopolizing its acquisition and distribution, Wahunsenacawh reinforced his preeminence and his ability to bestow favors upon loyal weroances. This economic control solidified his political authority, making him the central figure in a vast network of exchange.

Military Prowess and Diplomatic Finesse

The expansion and maintenance of the Powhatan Confederacy relied heavily on its military organization and Wahunsenacawh’s astute diplomatic skills. Warfare was a calculated tool of statecraft, aimed at subjugation, defense, and the assertion of dominance, rather than indiscriminate raiding.

All able-bodied men were expected to serve as warriors, trained from a young age in the use of bows and arrows, war clubs, and shields. While not a standing army in the European sense, Wahunsenacawh could quickly muster a formidable force from his various quiakohannocks when needed. His warriors were disciplined and effective, capable of both swift raids and sustained sieges.

Diplomacy was equally critical. Wahunsenacawh was a master negotiator, constantly assessing threats and opportunities. He formed alliances, mediated disputes, and leveraged strategic marriages to bind disparate groups together. The famous figure of Pocahontas, Wahunsenacawh’s daughter, serves as an example, though her later marriage to John Rolfe was unique and a direct response to English pressure. Earlier, her role would have been as a child diplomat, symbolizing her father’s willingness to engage with the English, albeit cautiously. The "Powhatan’s Mantle" concept – the idea that his authority provided protection and stability – was a powerful diplomatic message.

Encountering the English: A Clash of Empires

The arrival of the English at Jamestown fundamentally altered the dynamics of the Powhatan Confederacy. Wahunsenacawh initially viewed the English with a mixture of curiosity, suspicion, and strategic interest. He saw them as potential allies against rival tribes like the Monacan and Manahoac to the west, and as a source of valuable trade goods, particularly tools and weapons.

However, it quickly became clear that the English were not merely another tributary tribe or trading partner. Their insatiable demand for land, their unfamiliar agricultural practices, and their aggressive expansionist tendencies posed an existential threat to the Powhatan way of life and the integrity of the Confederacy. Wahunsenacawh masterfully played a long game, alternating between periods of trade and uneasy alliance, and phases of calculated hostility and siege, attempting to control, integrate, or ultimately expel the interlopers. He famously tried to starve them out, limit their access to resources, and absorb them into his system, albeit unsuccessfully.

His successor, his half-brother Opechancanough, continued this policy of resistance, leading the devastating attacks of 1622 and 1644. These desperate acts demonstrated the continued political will and military capacity of the Powhatan people, even as they faced overwhelming demographic and technological disadvantages.

Legacy and Reassessment

The Powhatan Confederacy, though ultimately fragmented and diminished by disease, warfare, and relentless English encroachment, left an indelible mark on history. Its sophisticated political organization challenges the simplistic narratives often applied to Native American societies. It was not a collection of isolated "tribes" but a dynamic, centralized political system, capable of complex governance, economic management, and strategic resistance.

The Confederacy’s decline was not due to a lack of political sophistication but rather the immense pressures of European colonization – the introduction of devastating diseases, the sheer numerical superiority of the English, and a fundamental clash over land ownership and resource exploitation. Yet, its structure allowed it to resist for decades, shaping the early history of Virginia and forcing the English to acknowledge a powerful indigenous state.

The legacy of the Powhatan Confederacy endures, a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of the Eastern Woodlands tribes. It stands as a powerful reminder that indigenous societies possessed intricate political systems, often more complex and effective than those they encountered, and that their interactions with European powers were not merely a story of conquest, but a profound clash of equally developed, albeit vastly different, civilizations.