The Unseen Heart of Seattle: The Duwamish Nation’s Enduring Fight for Federal Recognition

Seattle, a global hub of innovation and progress, proudly bears the name of Chief Si’ahl, a revered leader of the Suquamish and Duwamish tribes. Yet, in a profound historical irony, the very people who welcomed the first European settlers, whose ancestral lands form the foundation of this vibrant metropolis, remain unrecognized by the United States federal government. The Duwamish Nation, Seattle’s First People, are locked in a generations-long struggle for federal acknowledgment, a battle for their identity, sovereignty, and the basic rights afforded to other Indigenous nations across the country. Their fight is not merely for bureaucratic status; it is a profound quest for justice, self-determination, and a rightful place in the narrative of the city they call home.

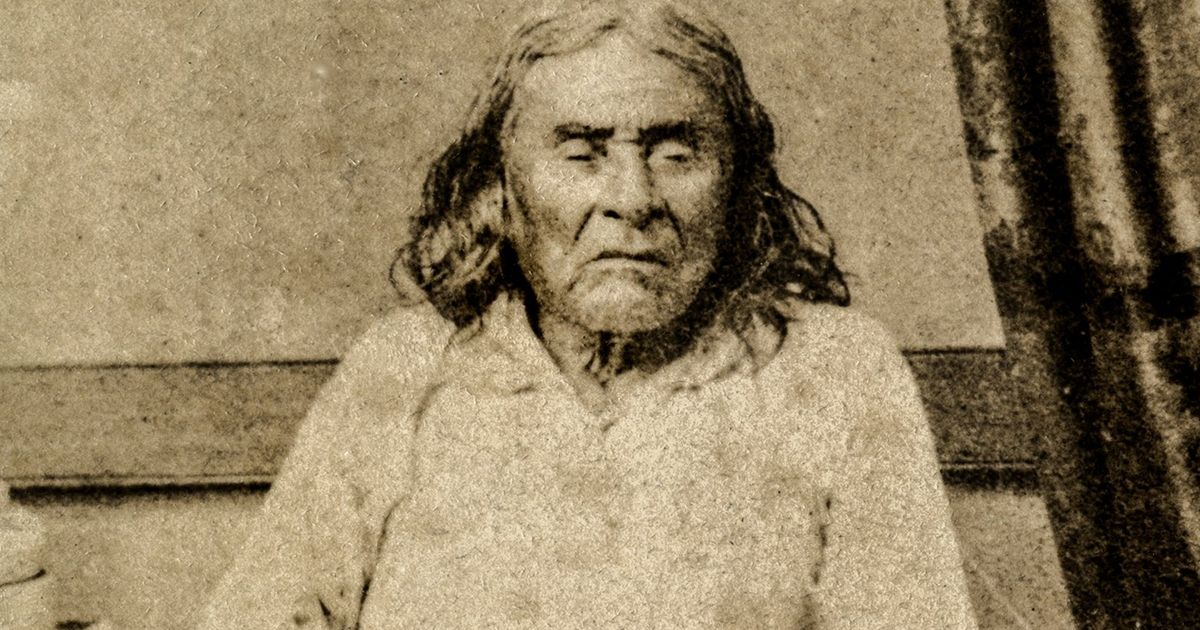

The story of the Duwamish is inextricably woven into the fabric of Seattle. Long before the arrival of white settlers in 1851, the Duwamish, a Lushootseed-speaking Coast Salish people, thrived on the rich lands and waters of the Puget Sound. Their villages dotted the shores of the Duwamish River, Lake Washington, and Elliott Bay, sustained by abundant salmon, shellfish, and game. Their culture was rich, their governance sophisticated, and their connection to the land spiritual and profound. It was Chief Si’ahl, or Chief Seattle as he became known, who famously offered a hand of friendship to the arriving Denny party, a gesture of peace that would ultimately lead to the displacement and disenfranchisement of his people.

The pivotal moment in their historical trajectory came with the signing of the Treaty of Point Elliott in 1855. Chief Seattle was a signatory to this treaty, which ceded vast tracts of Duwamish land to the U.S. government. In return, the treaty promised reservation lands, hunting and fishing rights, and other provisions. However, unlike many other tribes who signed the treaty, the Duwamish were never assigned a permanent, dedicated reservation. While some Duwamish people moved to the Muckleshoot or Suquamish reservations, many steadfastly refused to leave their ancestral territories, choosing to remain on their traditional lands, even as Seattle grew around them, engulfing their villages and transforming their environment. This crucial distinction – the lack of a federally established land base – would become a significant obstacle in their future bids for recognition.

The Duwamish’s journey through the labyrinthine federal recognition process has been arduous and fraught with disappointment. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), through its Office of Federal Acknowledgement (OFA), established in 1978, sets seven stringent criteria for tribes seeking federal status. These include demonstrating continuous existence as an Indian tribe since historical times, maintaining a distinct community, and exercising political authority over their members. For tribes like the Duwamish, who were dispossessed without a reservation and subjected to generations of forced assimilation, these criteria can be profoundly difficult to meet to the BIA’s satisfaction.

"We are still here. We never left," asserts Cecile Hansen, the elected Chairwoman of the Duwamish Tribe, a direct descendant of Chief Seattle, who has spearheaded the recognition fight for decades. Her words encapsulate the core of their argument: despite immense pressure, dispersal, and the absence of a federal land base, the Duwamish community has maintained its identity, culture, and political structure. They have consistently elected leaders, held cultural events, and striven to preserve their language and traditions.

Yet, the BIA has repeatedly denied their petition. In 2001, under the waning days of the Clinton administration, the Duwamish briefly achieved federal recognition, a moment of profound hope and vindication. This decision, however, was controversially reversed by the Bush administration just a year later, citing procedural errors. The BIA’s final denial in 2015 hinged on the argument that the Duwamish had not continuously maintained a "distinct community" and "political authority" as defined by the federal government since the 1850s, particularly due to their intermarriage with other tribes and non-Natives, and their lack of a formal reservation. Critics argue that such criteria fail to account for the unique historical trauma and adaptive strategies of tribes who were denied a land base and faced immense pressure to assimilate. How, they ask, can a government demand a community maintain specific, formal structures when that same government actively worked to dismantle their traditional ways of life?

The implications of non-recognition are vast and debilitating. Without federal status, the Duwamish Nation is denied access to critical federal funding for healthcare, housing, education, and cultural preservation programs. They cannot establish a tribal police force, operate a tribal court, or exercise sovereign jurisdiction over their lands (of which they possess only a small parcel, the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center). This lack of resources exacerbates health disparities, hinders educational opportunities, and makes the vital work of cultural revitalization incredibly challenging. While other federally recognized tribes in Washington State have been able to leverage federal support and, in some cases, tribal casinos, to rebuild their communities and economies, the Duwamish are left to rely on fundraising, grants, and the tireless efforts of their members.

Furthermore, non-recognition is a symbolic wound that cuts deep. It effectively erases their legal and historical existence as a distinct people in the eyes of the nation that occupies their ancestral land. It undermines their inherent sovereignty and diminishes their voice in regional and national dialogues concerning Indigenous rights and environmental justice. "It’s about dignity," Hansen often states. "It’s about being acknowledged for who we are, the First People of Seattle."

Despite these formidable challenges, the Duwamish Nation has never ceased its fight. The Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center, built in 2009 through community support, stands as a testament to their resilience. It serves as a vibrant hub for cultural events, language classes, and a gathering place for tribal members and the broader community. They continue to advocate through legal channels, political lobbying, and public education campaigns. Their cause has garnered significant support from local and state governments, who have passed resolutions acknowledging the Duwamish and calling for federal recognition. The City of Seattle, King County, and numerous organizations contribute to the Duwamish Tribe through "Real Rent Duwamish," a program that encourages non-Native residents to pay a monthly rent directly to the tribe as a tangible form of reconciliation and support.

The Duwamish struggle is not an isolated incident; it mirrors the battles of dozens of other unrecognized tribes across the United States. It highlights the inherent flaws and colonial biases embedded within the federal recognition process itself, a system often criticized for imposing a Western-centric view of what constitutes a "tribe." The BIA’s requirements, designed in the late 20th century, often fail to account for the devastating impacts of centuries of forced removal, assimilation policies, and the deliberate erosion of Indigenous governance structures.

The fight for Duwamish recognition is more than a legal or political issue; it is a moral imperative. Seattle, a city that prides itself on its progressive values and commitment to social justice, cannot truly reconcile with its past until it fully acknowledges and supports its founding people. Recognizing the Duwamish would be a profound act of historical justice, an affirmation of their enduring presence, and a powerful step towards genuine reconciliation. It would empower the Duwamish to access the resources necessary to thrive, to protect their cultural heritage, and to contribute their unique wisdom to the ongoing stewardship of the land and water that bears their ancestors’ spirit.

As the city continues to grow and evolve, the unwavering spirit of the Duwamish Nation serves as a powerful reminder of the deep historical layers beneath the urban landscape. Their fight for federal recognition is a beacon for Indigenous rights, a call to confront historical injustices, and a testament to the enduring strength of a people who, despite every adversity, proclaim with unwavering certainty: "We are still here. We never left." Their journey continues, and with it, the hope that one day, Seattle will not only bear the name of their great Chief but will also fully embrace and recognize his descendants.