Echoes in the Bark: Susquehannock Longhouse Living and the Enduring Spirit of Eastern Woodland Community

In the dense forests and fertile river valleys of what is now the northeastern United States, long before European footsteps disturbed the ancient soil, stood architectural marvels that were far more than mere shelters. These were the longhouses of the Eastern Woodland Tribes, and among the most prominent builders and inhabitants were the Susquehannock. Their longhouses were not just structures of wood and bark; they were living embodiments of community, spiritual connection, and a sophisticated social order, an architectural philosophy deeply rooted in the concept of communal existence.

To understand Susquehannock longhouse living is to peer into a worldview where individual identity was inextricably linked to the collective. The longhouse was the beating heart of their villages, a monumental testament to their ingenuity, resourcefulness, and profound understanding of their environment. It was a place where generations coexisted, where stories were spun by firelight, and where the very rhythm of daily life resonated with the pulse of the community.

The Architecture of Interconnectedness

The Susquehannock longhouse was a formidable and impressive structure, a marvel of organic engineering built without nails or metal tools. Typically elongated and rectangular, these communal dwellings could vary significantly in size, often stretching anywhere from 50 to over 200 feet in length, sometimes even reaching 400 feet, and approximately 20 to 25 feet in width and height. Imagine walking into a building as long as a football field, crafted entirely from the forest itself.

The primary materials were readily available: sturdy saplings and young trees, often hickory or oak, for the framework; flexible poles for the arched roof and walls; and large sheets of bark, predominantly elm or cedar, carefully stripped and overlapped like shingles, then secured with strips of basswood bark or rope. The construction was a communal effort, requiring coordinated labor and specialized knowledge passed down through generations. Men would fell and prepare the timber, while women gathered and processed the bark, often the more laborious task given the sheer volume required. The result was a surprisingly robust and weather-resistant dwelling, designed to withstand the harsh winters and humid summers of the region.

Internally, the longhouse was a masterpiece of functional design, reflecting the needs of its multiple inhabitants. A central aisle, usually about six to ten feet wide, ran the entire length of the structure, punctuated by a series of hearths—one for every two families, positioned directly beneath smoke holes in the roof. These hearths were not only sources of warmth and light but also focal points for cooking, gathering, and storytelling. Above the sleeping platforms, which lined both sides of the central aisle, were storage shelves, utilized for keeping personal belongings, food, and tools. Each family unit, often consisting of a mother, her daughters, and their husbands and children, would occupy a distinct section, marked by their hearth and platforms. This arrangement fostered privacy within the larger communal space, a delicate balance crucial for harmonious living.

"The longhouse was not just a house; it was a village under one roof," notes archaeologist Dr. William C. Johnson, emphasizing its role in shaping social interactions. "It literally housed the extended family and reflected the matrilineal structure of the society." This physical layout directly mirrored the Susquehannock’s social organization, where lineage was traced through the mother, and women held significant power and influence.

The Heartbeat of Community: Social Structure and Daily Life

The true essence of longhouse living lay not in its architecture alone, but in the vibrant community it nurtured. The Susquehannock, like many Iroquoian-speaking peoples, were a matrilineal society. This meant that descent was traced through the mother’s line, and women owned the longhouses and the agricultural fields. Clan mothers, often the eldest women in the longhouse, wielded considerable authority, influencing political decisions, controlling food distribution, and nominating male leaders.

Life within the longhouse was a constant negotiation of individual needs and communal responsibilities. Shared hearths meant shared meals, fostering a powerful sense of unity and mutual dependence. Children were raised collectively, with multiple adults contributing to their upbringing and education. Elders, repositories of wisdom and history, were revered, their stories and counsel guiding the community. The longhouse became a dynamic classroom, a sacred space for ceremonies, and a bustling hub of daily activity.

Daily life revolved around the seasons and the rhythms of the land. Women were the primary agriculturists, cultivating the "Three Sisters"—corn, beans, and squash—which formed the staple of their diet. They also gathered wild edibles, managed the forest resources, and prepared meals. Men were responsible for hunting, fishing, defense, and long-distance trade. The longhouse facilitated these roles by providing ample storage for dried foods, tools, and furs, and by serving as a central point for the distribution of resources.

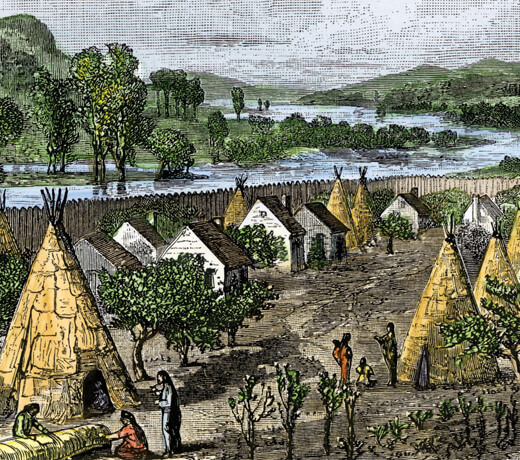

The communal nature extended beyond the walls. Susquehannock villages were typically fortified with strong palisades, often reaching 15-20 feet high, enclosing multiple longhouses, storage pits, and open ceremonial spaces. This defensive architecture underscored the importance of collective security in a landscape that could be both bountiful and dangerous, particularly as European incursions began to introduce new conflicts and pressures.

Spirituality and the Longhouse Worldview

For the Susquehannock, the longhouse was also a deeply spiritual space, a microcosm of the cosmos. The arched roof symbolized the dome of the sky, the smoke holes providing a direct conduit to the spirit world. The hearths represented the life-giving warmth of the sun and the enduring spirit of the family. The very act of building the longhouse was a spiritual endeavor, a collaboration with the natural world, giving thanks for the materials provided by the Creator.

Ceremonies and rituals, from naming ceremonies to harvest festivals, took place within its expansive confines. The longhouse was where dreams were shared, prophecies interpreted, and the collective memory of the people was reinforced through oral traditions. It was a space for healing, for celebration, and for mourning, connecting the living to their ancestors and to the forces that governed their world. The concept of the "Great Longhouse" often referred to the entire confederacy or the spiritual realm, emphasizing the profound symbolic power of the physical structure.

A Legacy Under Siege: European Contact and Decline

The Susquehannock thrived in the Susquehanna River Valley for centuries, their longhouses a testament to their enduring presence. However, the arrival of Europeans in the 17th century brought unprecedented challenges that ultimately led to their tragic decline. Initially, the Susquehannock engaged in robust trade with the Dutch and Swedes, exchanging furs for European goods like metal tools, firearms, and glass beads. This period saw them grow in power and influence, becoming formidable warriors and traders.

However, contact also introduced devastating European diseases to which the Susquehannock had no immunity. Epidemics of smallpox and measles ravaged their communities, drastically reducing their population. Concurrent conflicts with the expanding Iroquois Confederacy, particularly the Mohawk, further weakened them. Despite their resilience and military prowess, the cumulative pressures of disease, warfare, and land encroachment proved insurmountable. By the late 17th century, their numbers were drastically reduced, and many survivors were absorbed into other tribes or displaced from their ancestral lands. The once-bustling longhouses fell silent, eventually reclaimed by the very forests from which they were born.

Enduring Lessons from the Bark and Beam

Today, the Susquehannock longhouse stands as a poignant symbol, a powerful reminder of a sophisticated indigenous culture that flourished in North America. Archaeological excavations, such as those at the Washington Boro and Strickler sites in Pennsylvania, have meticulously uncovered the post molds and hearths that delineate the footprints of these magnificent structures, offering invaluable insights into Susquehannock life. These sites allow us to piece together the narratives of a people whose architecture was an extension of their social and spiritual fabric.

The lessons embedded in Susquehannock longhouse living resonate strongly in the modern world. Their architectural principles highlight sustainable building practices, utilizing local materials with minimal environmental impact. More profoundly, their communal living arrangement offers a blueprint for cooperation, resource sharing, and a deep sense of collective responsibility – values often lost in an increasingly individualized society. The longhouse reminds us of the power of a community built on mutual respect, shared purpose, and an intimate connection to the land.

While the physical longhouses of the Susquehannock may no longer stand, their spirit endures. They continue to inspire contemporary indigenous communities who are revitalizing traditional building practices and social structures. The longhouse remains a potent emblem of resilience, cultural continuity, and the profound wisdom of indigenous peoples, an architectural legacy that speaks volumes about the enduring human need for community, connection, and a place to call home, together.