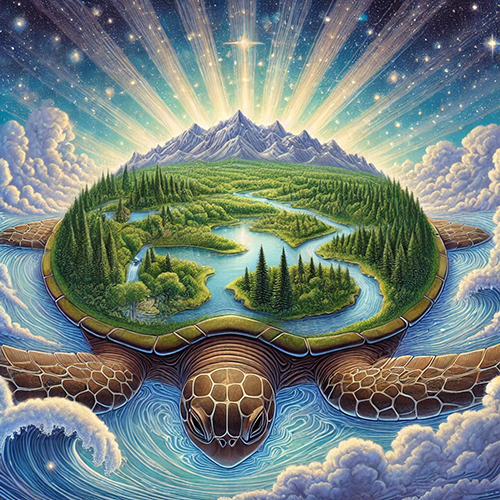

The Imperative of Land Back: Restoring Sovereignty and Stewardship on Turtle Island

The Land Back movement on Turtle Island is not merely a call for the return of territory; it is a profound demand for justice, sovereignty, and the restoration of ecological balance, rooted in Indigenous legal orders and a deep spiritual connection to the land. It directly challenges centuries of colonial dispossession, demanding that Indigenous nations reclaim their rightful place as stewards and decision-makers over their ancestral territories. This movement is not an abstract political concept but a living, breathing imperative for survival, cultural revitalization, and a sustainable future for all inhabitants of this continent.

Centuries of colonial policy, from the Doctrine of Discovery to forced assimilation, systematically dispossessed Indigenous nations of their ancestral lands, shattering traditional governance structures and severing the intricate relationship between people and place. The arrival of European settlers was predicated on the false premise of terra nullius – empty land – despite Turtle Island being home to hundreds of thriving, self-governing Indigenous nations. Treaties, often signed under duress or misunderstanding, were systematically broken, leading to the forceful removal of communities, the creation of reservations, and the relentless expansion of settler states. This historical trauma, deeply etched into the land and the memory of Indigenous peoples, manifests today in persistent social, economic, and health disparities. The consequences of this dispossession are not only human but also ecological, as colonial resource extraction and land management practices have driven unprecedented environmental degradation.

Land Back is fundamentally about Indigenous self-determination, recognizing that true sovereignty requires control over ancestral territories. It encompasses more than just fee-simple ownership; it involves the return of decision-making authority, the revitalization of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), and the re-establishment of Indigenous legal systems that have governed these lands for millennia. As Ktunaxa scholar and activist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson articulates, "Land Back is about restoring our relationships with the land, with our families, with our communities, and with our nations. It’s about remembering who we are as Indigenous peoples." It is a multi-faceted movement advocating for various forms of land return, including outright title transfer, co-management agreements, the creation of Indigenous protected areas, and the dismantling of colonial infrastructure that impedes Indigenous access and stewardship.

The benefits of supporting Land Back movements are transformative, extending far beyond Indigenous communities to encompass the well-being of the entire continent. For Indigenous peoples, the return of land is intrinsically linked to healing from intergenerational trauma. Research consistently shows that Indigenous communities with greater control over their lands and resources experience significantly better health outcomes, lower rates of poverty, and stronger cultural continuity. Access to traditional foods, medicines, and sacred sites is crucial for physical, mental, and spiritual health. Economic self-sufficiency is bolstered through the re-establishment of traditional economies and the ability to pursue culturally appropriate development. Political power is restored, allowing Indigenous nations to exercise their inherent right to self-governance, uphold their treaty responsibilities, and protect their cultural heritage for future generations.

Furthermore, Land Back is a critical component of climate justice and ecological restoration. Indigenous peoples, who comprise less than 5% of the world’s population, protect 80% of the planet’s biodiversity, often residing in areas critical for ecological stability. Their traditional ecological knowledge, developed over thousands of years of intimate observation and interaction with specific ecosystems, offers invaluable solutions to the climate crisis. Where Indigenous peoples maintain stewardship, forests are healthier, waters are cleaner, and biodiversity flourishes. For instance, a 2019 study published in Nature Sustainability found that lands managed by Indigenous communities globally exhibit biodiversity declines that are significantly lower than in other areas. Returning land to Indigenous hands means empowering those with the deepest knowledge and most profound vested interest in its long-term health. As Nick Estes, citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe and co-founder of The Red Nation, often states, "Land Back is climate justice." It offers a powerful alternative to the destructive resource extraction models that have historically plundered Indigenous territories and fueled environmental collapse.

For broader society, supporting Land Back represents an essential step towards true reconciliation. It moves beyond symbolic gestures to concrete actions that address historical injustices and build a more equitable future. It challenges settler societies to confront their colonial legacies and embrace new models of governance and relationship that honor Indigenous sovereignty. It also provides an opportunity for non-Indigenous people to learn from and collaborate with Indigenous nations, fostering a deeper understanding of sustainable living and respectful coexistence with the natural world.

The pathways to achieving Land Back are diverse and require multifaceted support. Governments, at all levels, have a crucial role to play by fulfilling treaty obligations, repatriating public lands, and establishing legislative frameworks that facilitate land transfer and Indigenous governance. In Canada, the federal government’s commitment to implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), particularly Article 26 which affirms Indigenous peoples’ right to their lands, territories, and resources, provides a framework for action. In the United States, mechanisms like the land-into-trust process, though often cumbersome, allow tribal nations to re-establish jurisdiction over their ancestral lands. However, these governmental processes are often slow and insufficient.

Grassroots movements and direct action remain vital. Indigenous land defenders often stand on the front lines, protecting sacred sites and vital ecosystems from industrial encroachment, asserting their inherent rights in the face of immense pressure. Supporting these movements means amplifying Indigenous voices, standing in solidarity, and challenging colonial narratives that demonize Indigenous resistance.

Non-Indigenous individuals and organizations also have a responsibility to act. This can take many forms:

- Financial Support: Contributing to Indigenous land trusts and rematriation funds, such as the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust in Ohlone territory (San Francisco Bay Area), which collects a voluntary "Shuumi Land Tax" from non-Indigenous residents to acquire and rematriate ancestral lands and build a vibrant Indigenous community.

- Education and Advocacy: Decolonizing personal knowledge and institutional practices, challenging settler myths, and advocating for policies that support Indigenous sovereignty and land rights within schools, workplaces, and communities.

- Building Relationships: Engaging with local Indigenous communities, learning about their history, culture, and current struggles, and offering support in ways identified by Indigenous leadership.

- Returning Land Directly: In some cases, private landowners are choosing to return portions of their property to local Indigenous nations or land trusts, recognizing the moral imperative to do so. This act of "re-matriation" is a powerful model for direct reconciliation.

- Co-management and Easements: Supporting the creation of co-management agreements for national parks and protected areas, where Indigenous knowledge and governance are integrated into conservation efforts. Examples include the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah, which was re-established with an inter-tribal co-management commission.

Addressing common misconceptions is also crucial. Land Back is not about expelling non-Indigenous people en masse, nor is it a monolithic demand. It is about restoring proper relationships, respecting Indigenous sovereignty, and sharing the benefits of the land’s stewardship. Many Land Back initiatives focus on culturally significant sites, ecological restoration, or the return of public lands, rather than private property. The goal is to dismantle colonial power structures, not to replicate them. It is about re-establishing Indigenous governance and ensuring Indigenous peoples have the authority to manage and protect their homelands for the benefit of all, grounded in their ancient responsibilities to the land.

Supporting Land Back is not just an act of historical redress; it is an investment in a more just, sustainable, and equitable future for all inhabitants of Turtle Island. It demands a fundamental shift in perspective, moving away from extractive, exploitative relationships with the land and towards reciprocal, respectful stewardship. By actively engaging with and championing Indigenous Land Back movements, we can contribute to healing historical wounds, fostering genuine reconciliation, and building a world where Indigenous sovereignty thrives, and the land, in turn, can heal. The time for genuine action, beyond words and symbolic gestures, is now.