Guardians of the Land: The Enduring Struggle for Tribal Sovereignty over Natural Resources

For millennia, Indigenous nations across North America have been the original stewards of the land, their cultures, spiritual beliefs, and very survival intricately woven into the fabric of the natural world around them. From the life-giving salmon runs of the Pacific Northwest to the vast mineral wealth beneath the Southwestern deserts, these resources sustained vibrant societies long before European contact. Today, the concept of tribal sovereignty over natural resources remains a cornerstone of Indigenous self-determination, a testament to an enduring fight for control over ancestral lands and the inherent right to manage what sustains them.

This struggle, however, is far from over. Despite a legal framework that ostensibly recognizes tribal sovereignty, the reality on the ground often involves complex jurisdictional battles, resource exploitation, and environmental justice issues that disproportionately impact Indigenous communities. Understanding this ongoing dynamic requires delving into history, law, economics, and the profound cultural significance these resources hold.

The Foundation of Sovereignty: A Nation-to-Nation Relationship

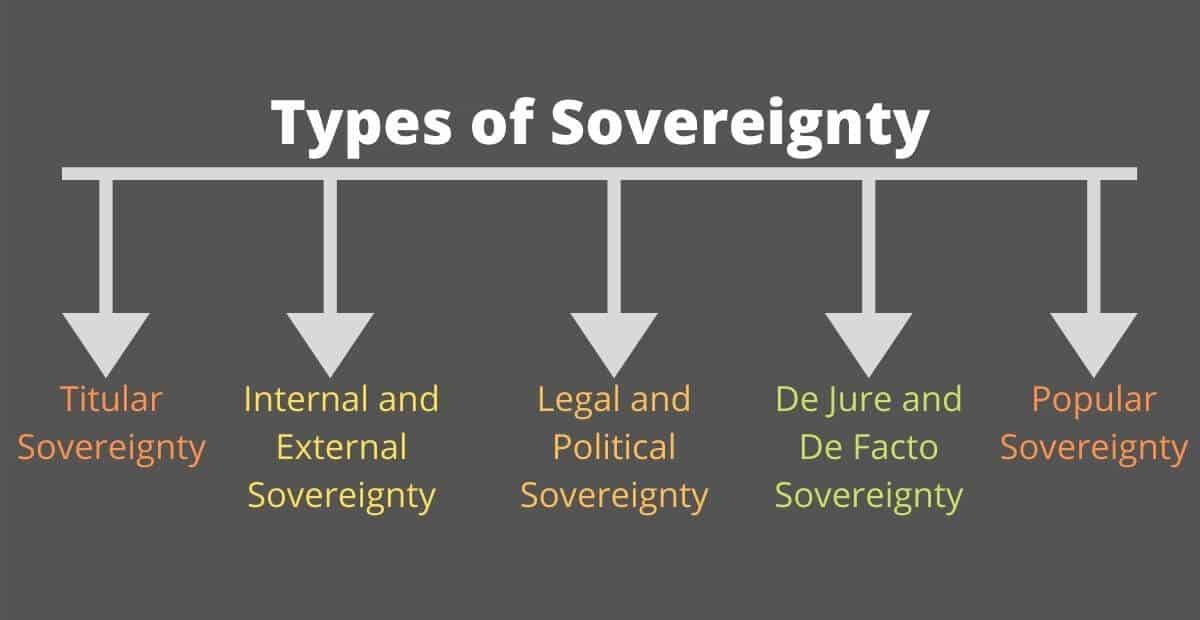

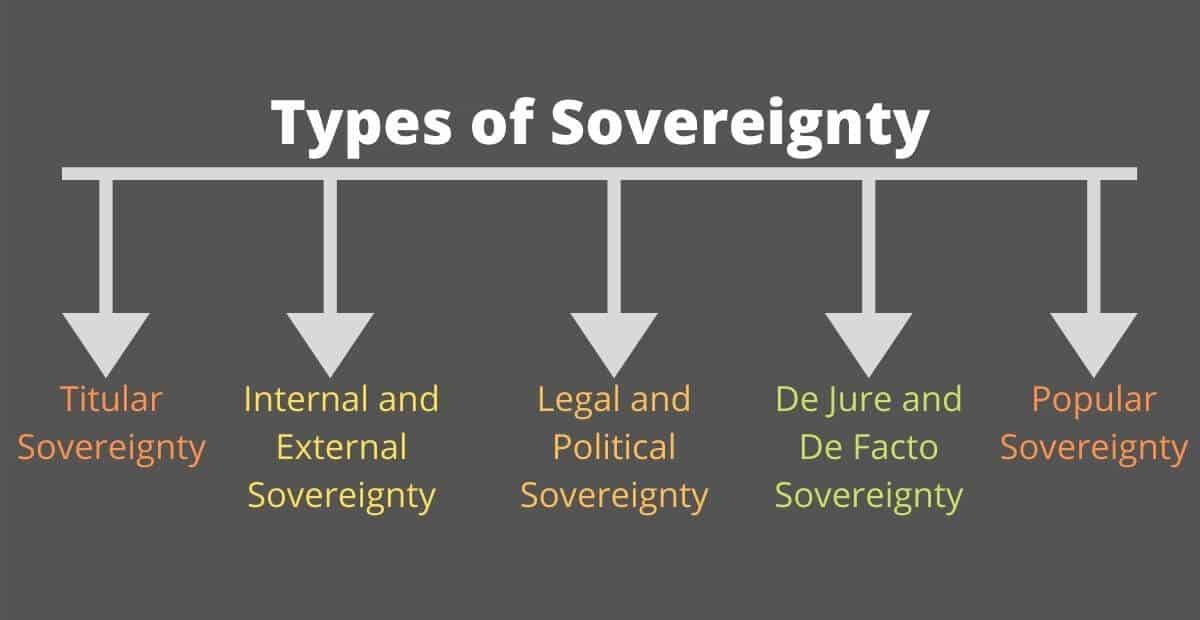

At its core, tribal sovereignty is the inherent right of Indigenous nations to govern themselves, their lands, and their people. It predates the formation of the United States and has been affirmed, albeit often inconsistently, through treaties, federal statutes, and Supreme Court decisions. When it comes to natural resources, this sovereignty means the right to control, manage, develop, and protect the air, water, land, and minerals within their territories.

The principle of "reserved rights" is central here. Treaties, often seen by the U.S. government as grants of land from tribes, are interpreted by Indigenous nations as solemn agreements where they reserved rights and resources not explicitly ceded. As Justice George Boldt famously declared in the landmark 1974 United States v. Washington (Boldt Decision) regarding treaty fishing rights: "Treaties were not a grant of rights to the Indians, but a grant of rights from them—a reservation of those not granted." This concept underpins many tribal claims to natural resources today.

Another crucial legal concept is the "trust responsibility," which obligates the U.S. federal government to protect tribal lands, resources, and self-governance. While often falling short in practice, this responsibility provides a legal lever for tribes to demand federal action against external threats to their resources.

Water is Life: The Cornerstone of Resource Sovereignty

Perhaps no natural resource illustrates the complexities and critical importance of tribal sovereignty more acutely than water. Arid regions across the American West have long been battlegrounds for water rights, and Indigenous nations hold some of the oldest and most senior claims. The 1908 Supreme Court case Winters v. United States established the "Winters Doctrine," affirming that when reservations were created, either by treaty or executive order, tribes implicitly reserved enough water to fulfill the purposes of their reservation, including agriculture, domestic use, and cultural practices.

This doctrine has been pivotal, yet its implementation has been slow and contentious. Many tribes have spent decades, even a century, negotiating water settlements with state and federal governments, often facing well-established non-Indian water users who fear losing their allocations. For tribes like the Navajo Nation, whose lands span parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, securing adequate water for their vast territory is not merely an economic issue but a matter of health, cultural survival, and the ability to sustain communities. The Navajo Nation, for example, is still working to fully quantify and utilize its decreed water rights, facing immense infrastructure challenges to deliver water to remote homes where many still lack running water.

"For us, water is the first medicine," explained Diné Elder and activist, Kee Yazzie, during a recent environmental conference. "It is sacred. To control our water is to control our destiny, to keep our traditions alive for the next generations."

The Double-Edged Sword: Minerals, Energy, and Environmental Justice

Tribal lands are often resource-rich, holding significant deposits of coal, oil, natural gas, uranium, and other minerals. This has historically been a double-edged sword. While these resources represent potential economic development and self-sufficiency, their extraction has frequently come at a devastating cost to the environment and public health of tribal communities, often without adequate consent or fair compensation.

The Navajo Nation’s experience with uranium mining in the mid-20th century is a stark example. During the Cold War, thousands of uranium mines operated on Navajo lands, providing critical resources for the U.S. nuclear program. Yet, without proper safety regulations or information, Navajo miners suffered from lung cancer and other radiation-related illnesses, and their lands and water sources were left contaminated. The legacy of abandoned uranium mines continues to plague the Navajo Nation, a painful reminder of resource extraction without true sovereign control.

More recently, the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) saga at Standing Rock galvanized international attention to tribal sovereignty over natural resources. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe fiercely opposed the pipeline’s route, arguing it threatened their sole source of drinking water, sacred sites, and cultural heritage. Their resistance highlighted how federal agencies often prioritize corporate interests over treaty obligations and environmental protections, forcing tribes to fight for their rights in court and through direct action. While the pipeline ultimately became operational, the movement underscored the power of tribal advocacy and the enduring spiritual connection Indigenous peoples have to their lands and waters.

Conversely, some tribes are leveraging their resource sovereignty to pursue sustainable economic development. The Campo Kumeyaay Nation in Southern California, for instance, operates one of the first and largest tribal-owned wind farms, generating revenue while providing clean energy. This demonstrates a proactive approach to resource management that aligns economic goals with environmental stewardship and tribal values.

Forests, Fisheries, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Beyond water and minerals, tribes also assert sovereignty over their forests and fisheries, often demonstrating sophisticated traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) that offers valuable lessons for broader conservation efforts. In the Pacific Northwest, treaty rights to salmon fishing have been a consistent battleground, but also a source of cultural resilience. Tribes like the Lummi Nation and the Nez Perce Tribe have fought tirelessly to protect salmon habitats, engaging in co-management agreements with state and federal agencies and advocating for dam removal to restore fish runs. Their knowledge of river systems, fish cycles, and sustainable harvesting practices has been passed down through generations, making them indispensable partners in ecosystem restoration.

Similarly, many tribes are reclaiming management of their forest lands, moving away from extractive timber practices towards holistic, culturally informed forestry that prioritizes biodiversity, wildlife habitat, and spiritual connection. The Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin is renowned for its sustainable forestry practices, having managed their forest for over 150 years without depletion, proving that economic prosperity and ecological health can coexist. Their approach, rooted in their traditional belief system, yields high-quality timber while maintaining the forest’s health and integrity.

The Path Forward: Self-Determination and Environmental Justice

The ongoing struggle for tribal sovereignty over natural resources is a multifaceted fight for justice, self-determination, and the recognition of inherent rights. It’s a fight that demands greater federal respect for treaty obligations, more robust consultation processes, and stronger legal protections against environmental degradation.

Tribes are increasingly building their own technical and legal capacity to manage their resources, establishing sophisticated environmental departments, legal teams, and economic development corporations. They are also forging alliances with environmental groups, academics, and other Indigenous nations to amplify their voices on national and international stages.

The principle of "free, prior, and informed consent" (FPIC), enshrined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, is gaining traction as a standard for any development project impacting tribal lands. This means that tribes must be consulted and agree to projects before they proceed, not merely informed after decisions have been made.

Ultimately, respecting tribal sovereignty over natural resources is not just about legal compliance; it’s about acknowledging the deep historical injustices, empowering communities to determine their own futures, and recognizing the invaluable contributions of Indigenous peoples to environmental stewardship and sustainable living. In a world grappling with climate change and ecological crises, the traditional ecological knowledge and sovereign management practices of Indigenous nations offer crucial pathways towards a more balanced and sustainable relationship with the Earth. Their enduring struggle is a reminder that true sovereignty is inextricably linked to the health and vitality of the land that sustains us all.