The Linguistic Tapestry of the Southeast: Untangling Indigenous Language Families

The Southeastern United States, a region often romanticized for its lush landscapes and complex history, was once a vibrant mosaic of human languages, each a unique expression of culture, knowledge, and connection to the land. Before European contact irrevocably altered its course, this area hosted an astonishing linguistic diversity, a testament to millennia of human migration and adaptation. Classifying these indigenous language families is not merely an academic exercise; it is an act of historical recovery, a profound effort to understand the deep past of human societies, their movements, interactions, and the very structure of their thought. Yet, the task is fraught with challenges, as centuries of colonization, disease, warfare, and forced removals have silenced many voices, leaving behind fragments and mysteries that linguists continue to piece together.

At the heart of Southeastern linguistic classification lies the monumental task of distinguishing genetic relationships—languages descended from a common ancestor—from contact-induced similarities, or those languages that stand as isolates, their origins obscured by time and loss. The region’s indigenous languages largely fall into a few well-established families, alongside a scattering of isolates and a tragic number of languages that vanished before adequate documentation could preserve them.

The Dominant Strains: Muskogean and Iroquoian

Foremost among the Southeastern families is Muskogean, a robust and widely distributed group that dominates the linguistic landscape. Its speakers traditionally occupied vast stretches from the Mississippi River eastward to the Atlantic coast, encompassing present-day Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, and parts of Tennessee and South Carolina. The Muskogean family is generally divided into two main branches: Western and Eastern.

The Western Muskogean branch includes Choctaw and Chickasaw, two closely related languages once spoken across Mississippi and Alabama. Their speakers were among the first to face forced removal to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) during the infamous Trail of Tears. Both languages are renowned for their intricate verbal morphology and complex agreement systems, where verbs can carry a remarkable amount of information about the subject, object, and even the manner of action.

The Eastern Muskogean branch is more diverse, encompassing languages like Mvskoke (Creek/Seminole), Alabama, Koasati, and historically, Hitchiti and Apalachee. Mvskoke, the language of the Creek Confederacy, was a significant lingua franca in the Southeast and remains a vibrant language today, primarily in Oklahoma and Florida. Its extensive vowel harmony system and rich inflectional morphology are key features. The now-extinct Apalachee, spoken in the Florida panhandle, provided early insights into the family’s ancient forms through 17th-century Spanish mission documents. The sheer geographic spread and internal diversity of Muskogean languages underscore a deep history of migration and diversification within the region.

Another major player, though with a distinct geographic focus, is Iroquoian, specifically its Southern branch, represented almost exclusively by Cherokee. While the bulk of the Iroquoian family—including Mohawk, Seneca, and Oneida—is found in the Northeast, Cherokee forms a vital, albeit geographically distant, extension. Its traditional homeland spanned the southern Appalachian Mountains, in parts of present-day North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama. Cherokee stands out not only for its unique phonology and rich polysynthetic structure, where entire sentences can be expressed in a single verb, but also for its remarkable history of literacy. The creation of the Cherokee syllabary by Sequoyah in the early 19th century was a monumental achievement. "Within a few years of its invention," noted linguist Willard Walker, "the Cherokee people achieved a literacy rate higher than that of their white neighbors," demonstrating the ingenuity and adaptability of the language and its speakers. This independent development of a writing system is a powerful testament to the intellectual capacity and cultural resilience of the Cherokee Nation.

The Scattered Remnants: Siouan-Catawban and Caddoan

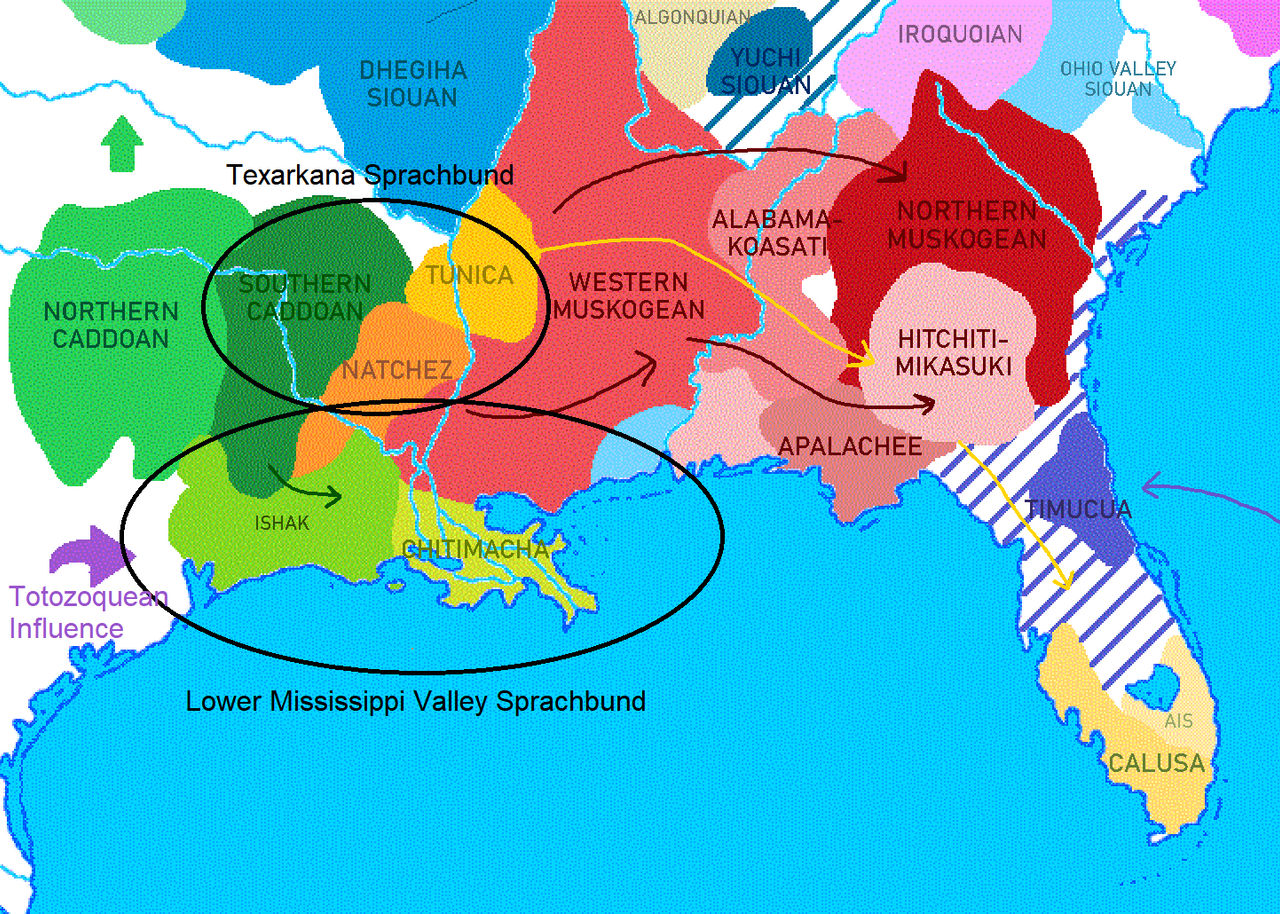

Beyond the well-defined Muskogean and Iroquoian families, the Southeastern linguistic landscape becomes more fragmented, revealing ancient migrations and deeper layers of history. The Siouan-Catawban family is particularly intriguing. While most Siouan languages are found in the Great Plains, a distinct Southeastern branch existed, including languages like Ofo and Biloxi (both extinct), once spoken along the lower Mississippi River, and Tutelo, spoken in Virginia and North Carolina. Their presence in the Southeast suggests ancient westward migrations or a much broader historical distribution of Siouan peoples.

Even more distinct is the Catawban branch, represented by Catawba itself, spoken in the Carolinas, and its close relative, Woccon (extinct). Catawba, now critically endangered, possesses linguistic features that set it apart from other Siouan languages, leading many linguists to classify it as a separate, albeit distantly related, branch within a larger Siouan-Catawban macrophylum. The fragmentation and near-extinction of these languages make their reconstruction and precise classification immensely challenging, offering tantalizing glimpses into a prehistory that is still largely unwritten.

The Caddoan family, though primarily associated with the Southern Plains (e.g., Wichita, Pawnee), also had a significant Southeastern presence, most notably with Caddo proper. The Caddo people traditionally inhabited areas of eastern Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. Caddo languages are known for their highly complex verbal morphology, utilizing an array of prefixes and suffixes to convey subtle nuances of meaning, aspect, and modality. Their placement within the Southeast underscores the fluidity of cultural and linguistic boundaries, particularly in the borderlands between the forest and the plains.

The Enigmatic Isolates and Vanished Voices

Perhaps the most poignant and challenging aspect of Southeastern linguistic classification involves the isolates—languages that show no demonstrable genetic relationship to any other known language family—and the numerous languages that disappeared with minimal, if any, documentation.

Natchez, spoken by a people historically centered near present-day Natchez, Mississippi, is a prime example of an isolate. While some linguists have proposed a distant connection to Muskogean, the evidence remains inconclusive, leading most to treat it as a distinct linguistic entity. Similarly, Tunica, spoken along the lower Mississippi, and Chitimacha, from southern Louisiana, are also considered isolates, each a linguistic island in a sea of other languages. Their unique phonological and grammatical structures represent distinct evolutionary paths, offering invaluable, albeit limited, insights into deep human linguistic diversity.

Yuchi (Euchee), traditionally spoken in eastern Tennessee and parts of Georgia, is another striking isolate. Its linguistic structure is so profoundly different from its neighbors that it stands as a testament to its long, independent history. "The Yuchi language," as linguist Mary Linn observes, "is a linguistic outlier, a puzzle that has resisted easy classification, hinting at ancient migrations and population movements that predate most of our current understanding." Its very existence challenges neat categorizations and underscores the ancient layers of human settlement in the Southeast.

Then there are the "ghosts" of languages, those that vanished with little more than a name or a handful of words: Timucua (Florida/Georgia), Atakapa (Louisiana/Texas), Karankawa (Texas), Calusa (Florida), Guale (Georgia), and Yamasee (South Carolina/Georgia), among others. These languages represent a tragic void in our understanding. The scarcity of data—often limited to short word lists collected by early explorers or missionaries—makes definitive classification impossible. Were they isolates? Did they belong to larger, now-lost families? These questions may never be fully answered, a stark reminder of the immense cultural and intellectual loss inflicted by colonization.

Challenges and the Path Forward

The classification of Southeastern Indigenous languages is a deeply complex endeavor, challenged by several critical factors. First, the sheer volume of language loss means that many potential connections and branches are forever obscured. Entire communities and their languages were eradicated before linguists could even begin systematic documentation. Second, the region was a crucible of language contact, leading to extensive borrowing of words, sounds, and even grammatical features between unrelated groups. This makes disentangling genetic relationships from areal features (shared features due to proximity, not common ancestry) exceedingly difficult. Third, the forced removal policies of the 19th century further complicated the picture, mixing previously distinct linguistic communities and accelerating language shift as people struggled to survive in new environments.

Despite these challenges, ongoing linguistic research, often in collaboration with tribal communities, continues to yield new insights. Modern comparative methods, coupled with archaeological and genetic evidence, are slowly illuminating the deep past. Understanding these classifications is not merely an academic pursuit; it is fundamental to language revitalization efforts. By knowing a language’s relatives, linguists and community members can draw upon related languages to reconstruct lost vocabulary or grammatical structures, breathing new life into endangered tongues.

Ultimately, the classification of Southeastern Indigenous language families paints a picture of profound diversity, ancient migrations, and the tragic consequences of historical upheaval. Each language, whether vibrant or a whisper from the past, represents a unique way of seeing the world, a repository of traditional knowledge, and an irreplaceable part of humanity’s shared heritage. The ongoing effort to understand and classify them is a testament to the enduring power of language and the unwavering commitment to honoring the voices that shaped the heart of America.