Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English about Sioux land management in South Dakota.

Guardians of the Plains: Lakota Land Management in South Dakota

The wind, an ancient whisper across the vast, rolling plains of South Dakota, carries with it the echoes of generations. For the Lakota people, part of the larger Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires of the Great Sioux Nation), this land is not merely territory; it is the essence of their identity, their spiritual anchor, and the wellspring of their culture. Today, on reservations like Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and Cheyenne River, the challenge of managing this sacred earth is a complex tapestry woven from traditional ecological knowledge, federal regulations, economic aspirations, and the enduring legacy of historical trauma.

At its core, Lakota land management is a profound exercise in self-determination, a continuous effort to restore balance and sovereignty after centuries of dispossession. It is a story of resilience, innovation, and a deeply ingrained responsibility to future generations, guided by the wisdom of the past.

A Legacy of Land and Loss

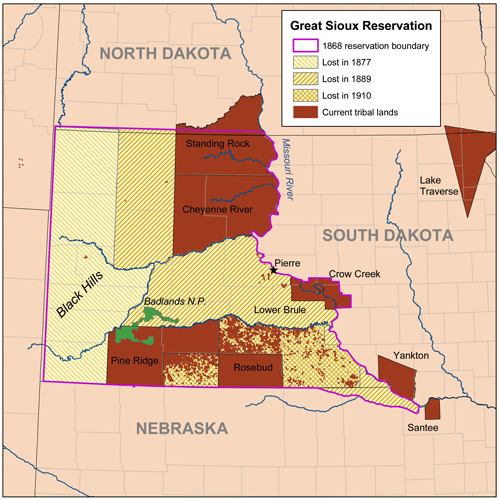

To understand contemporary Lakota land management, one must first grasp the historical context. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, intended to secure a "Great Sioux Reservation" for the Lakota people, promised vast tracts of land, including the sacred Paha Sapa, the Black Hills. Yet, the discovery of gold swiftly led to the treaty’s abrogation, a land grab, and a series of conflicts that culminated in the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. The land base was drastically reduced, carved into smaller, often checkerboarded reservations, with much of the prime agricultural and grazing land sold off to non-Native settlers or held in trust by the federal government’s Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

This history of broken promises and land theft created a complex legal and practical landscape. Today, tribal governments operate within a system where much of their land is held in "trust" by the BIA, complicating management decisions, resource development, and even simple land use permits. This jurisdictional maze, often referred to as "checkerboard ownership" due to the mix of tribal, individual Native, and non-Native private land within reservation boundaries, presents a significant hurdle to cohesive, long-term land management planning.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge: The Guiding Philosophy

Despite these external complexities, the bedrock of Lakota land management remains the deep-seated philosophy of Wo Lakota – a holistic worldview emphasizing interconnectedness and respect for all living things. Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), passed down through generations, provides a framework for understanding and interacting with the natural world.

"Our ancestors lived in harmony with this land for thousands of years," explains Basil Brave Heart, an Oglala Lakota elder and educator from Pine Ridge. "They understood the cycles of the buffalo, the health of the grasslands, the flow of the rivers. This knowledge isn’t just about survival; it’s about spiritual connection and our identity as Lakota people. We are the land, and the land is us."

This philosophy translates into practical management strategies focused on sustainability, biodiversity, and the restoration of natural processes. It contrasts sharply with purely extractive or short-term profit-driven approaches, prioritizing long-term ecological health and cultural preservation.

Reclaiming the Buffalo: A Symbol of Renewal

Perhaps the most iconic and successful example of Lakota land management is the reintroduction of Tatanka (buffalo or bison) to the plains. Once numbering in the tens of millions, buffalo were nearly eradicated in the 19th century as a tactic to subdue Native American tribes. Their return is a powerful symbol of cultural resurgence and ecological restoration.

On reservations like Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and Cheyenne River, tribal land managers, often in collaboration with organizations like the InterTribal Buffalo Council, are actively establishing and expanding buffalo herds. These efforts are multi-faceted:

- Ecological Restoration: Bison are keystone species. Their grazing patterns promote grassland health, enhance biodiversity by creating diverse habitats, and help sequester carbon.

- Cultural Revitalization: The buffalo is central to Lakota spirituality, ceremonies, and sustenance. Its return reconnects people with their heritage.

- Economic Development: Buffalo provide a sustainable source of lean, healthy meat, creating local jobs through ranching, processing, and sales. Some tribes are also developing eco-tourism centered around their buffalo herds.

"Bringing the buffalo back isn’t just about animals; it’s about bringing ourselves back," says a Cheyenne River Sioux Tribal Parks and Recreation manager. "It’s about healing the land and healing our people."

Grasslands and Sustainable Ranching

Beyond buffalo, the vast grasslands are another critical component of Lakota land management. Many tribal members are skilled ranchers, continuing a tradition that adapted after the buffalo’s decline. However, the management of these grasslands is evolving. Instead of simply maximizing cattle numbers, a growing emphasis is placed on sustainable grazing practices that mimic natural patterns.

Rotational grazing, deferred grazing, and careful stocking rates are employed to prevent overgrazing, allow native grasses to recover, and improve soil health. These practices are crucial for drought resilience, a growing concern in a region susceptible to extreme weather events exacerbated by climate change. Tribal land departments often work with federal agencies like the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to access technical assistance and funding for these sustainable practices, while ensuring that tribal sovereignty over land use decisions remains paramount.

Water Rights and Resource Protection

Water, particularly from the Missouri River and its tributaries, is lifeblood for the Lakota people. Historically, their water rights were often ignored or underdeveloped, leading to challenges in agriculture and municipal water supplies. Today, tribes are asserting their inherent water rights, engaging in complex legal battles and negotiations to ensure adequate access for irrigation, drinking water, and ecological needs. Protecting water quality from industrial pollution, agricultural runoff, and potential mining operations remains a constant vigilance.

The specter of resource extraction, particularly oil and gas, also looms. While some see potential for economic development, others express deep concern over environmental degradation, water contamination, and the disruption of sacred sites. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline, while primarily in North Dakota, highlighted the intense struggle many Lakota communities face in balancing economic pressures with the profound responsibility to protect their land and water for future generations.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite these inspiring efforts, significant challenges persist. High rates of poverty and unemployment on reservations often force difficult choices between economic development and environmental protection. Limited access to capital, infrastructure, and technical expertise can hinder ambitious land management projects. The complex web of federal regulations and the legacy of BIA trust land management can be bureaucratic and slow, impeding tribal self-governance.

Climate change also presents an existential threat. Increased frequency of droughts, wildfires, and extreme weather events directly impacts traditional livelihoods, agricultural productivity, and the health of ecosystems. Lakota land managers are actively seeking ways to build resilience, from water conservation techniques to fire management strategies that incorporate traditional burning practices.

Yet, the vision for the future is clear: increased self-determination and the full exercise of tribal sovereignty over their lands. This includes:

- Consolidating Land Holdings: Efforts to acquire individually allotted lands and return them to tribal ownership help streamline management and strengthen tribal control.

- Economic Diversification: Beyond traditional ranching, tribes are exploring renewable energy projects (wind and solar), sustainable tourism, and other enterprises that align with their values.

- Youth Engagement: Educating and involving younger generations in land management practices ensures the continuity of TEK and fosters a new generation of environmental stewards.

- Policy Advocacy: Tribes continue to advocate at federal and state levels for policies that respect treaty rights, streamline land management processes, and provide equitable resources.

The Lakota people’s journey in land management is an ongoing testament to their enduring spirit. It is a powerful reminder that land is more than property; it is a living entity, a cultural repository, and a sacred trust. As the wind sweeps across the South Dakota plains, it carries not just echoes of the past, but the determined voices of those who continue to guard their sacred earth, ensuring its health and vitality for the seven generations yet to come. Their work offers a vital lesson in sustainability, resilience, and the profound wisdom that comes from living in true kinship with the land.