Echoes of the Sacred: Native American Prophets and the Unseen War for Survival in the Colonial Era

The vast, ancient lands of North America, once a tapestry of diverse Indigenous nations, were irrevocably transformed by the arrival of European colonists. This encounter unleashed a torrent of devastation: disease, land dispossession, economic disruption, and the relentless assault on traditional ways of life. Yet, amidst this profound crisis, a different kind of leader emerged – not warriors wielding axes, but prophets speaking of spiritual renewal, moral reform, and a path back to sovereignty. These Native American prophets of the colonial era were more than just religious figures; they were crucial cultural architects, political unifiers, and spiritual anchors who sought to re-establish balance in a world thrown violently off course. Their visions, often born from profound personal suffering and divine revelation, offered hope, galvanized resistance, and laid the foundations for enduring cultural resilience.

The colonial era, spanning from the 17th to the early 19th centuries, was a period of existential threat for Indigenous peoples. European diseases decimated populations, leading to a loss of elders and traditional knowledge. The insatiable demand for land pushed communities to the brink, while the introduction of alcohol, firearms, and new trade goods disrupted social structures and economies. As traditional political and military solutions often proved insufficient against the technologically superior and demographically overwhelming colonial powers, many Native communities turned inward, seeking answers in the spiritual realm. This desperation created fertile ground for individuals who claimed direct communication with the Creator or ancestral spirits, offering a divine mandate for change.

These prophets often shared common themes in their messages. Foremost was a call for moral and spiritual purification, which frequently involved a strict rejection of European vices, particularly alcohol. They advocated a return to traditional Indigenous values, ceremonies, and communal living, often urging followers to abandon European material goods and assimilate into neither colonial nor missionary ways. Crucially, many prophets envisioned a pan-Indian unity, recognizing that the threat was not just from one colonial power but from the entire European presence, necessitating a collective Indigenous response. Their spiritual authority often translated into immense political influence, enabling them to unite disparate groups and inspire movements of both peaceful reform and armed resistance.

One of the earliest and most influential of these figures was the Lenape (Delaware) prophet, Neolin, whose visions in the 1760s profoundly impacted the burgeoning resistance movement known as Pontiac’s Rebellion. Neolin, also known as the "Delaware Prophet," experienced a series of profound revelations, including a journey to the "Master of Life." He preached that the Indigenous peoples had strayed from the "right path" by adopting European customs and goods, particularly alcohol and Christianity. The Master of Life, he recounted, had revealed a path back to strength and prosperity: "I am the Master of Life, and I created the Indians, not the white man… Therefore, drive them out of your country, make war upon them."

Neolin’s message was a powerful rejection of colonial influence and a call for cultural revitalization. He taught his followers to abandon European tools, clothing, and food, and to revert to traditional hunting, crafts, and ceremonies. His vision of a unified Indigenous identity, transcending tribal divisions, resonated deeply with leaders like the Ottawa chief Pontiac, who adopted Neolin’s teachings as the ideological backbone for his widespread uprising against British rule in the Great Lakes region. Though Pontiac’s Rebellion ultimately failed to dislodge the British, Neolin’s spiritual message demonstrated the potent force of prophetic leadership in mobilizing resistance and reaffirming Indigenous identity in the face of overwhelming odds.

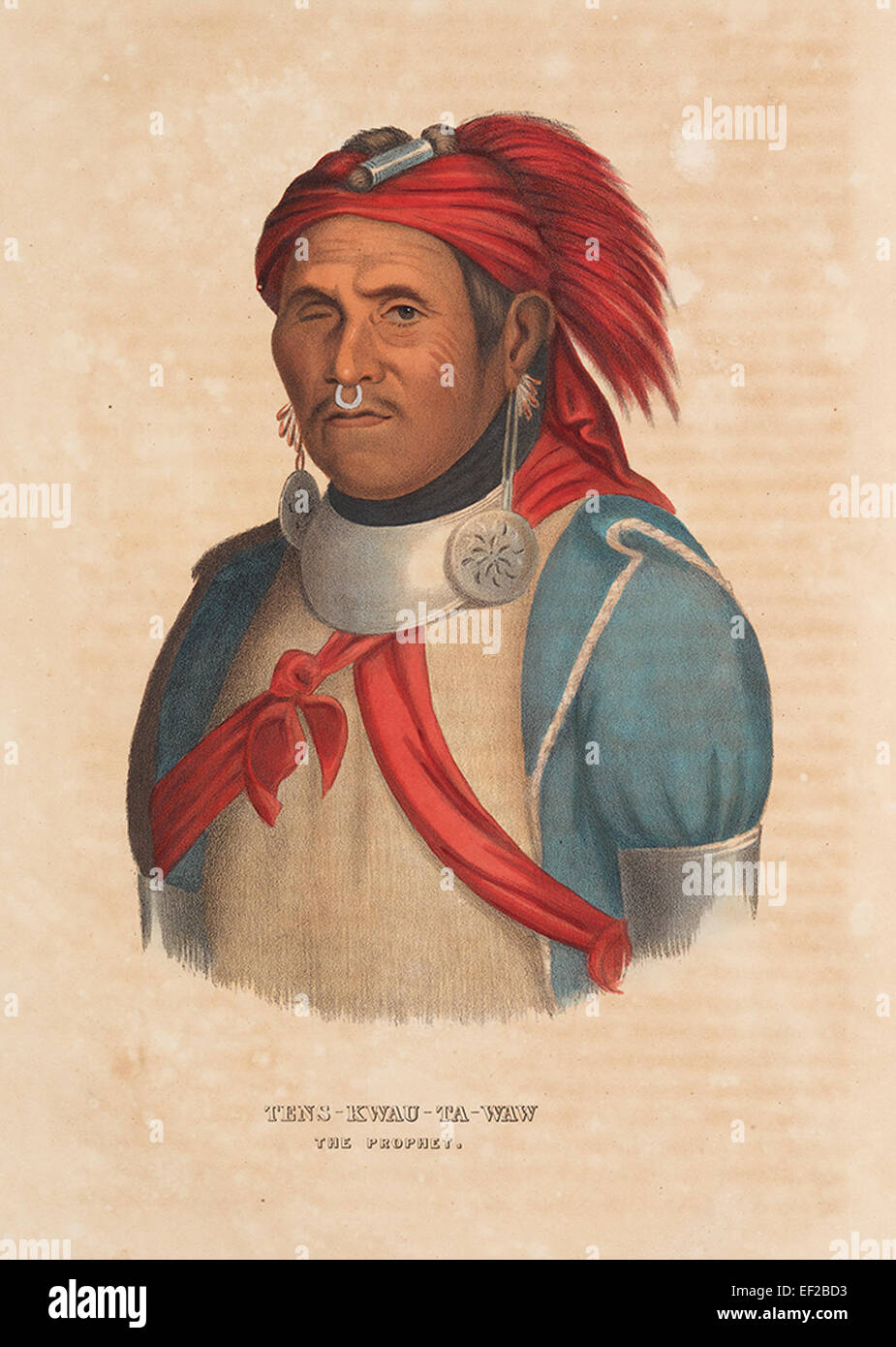

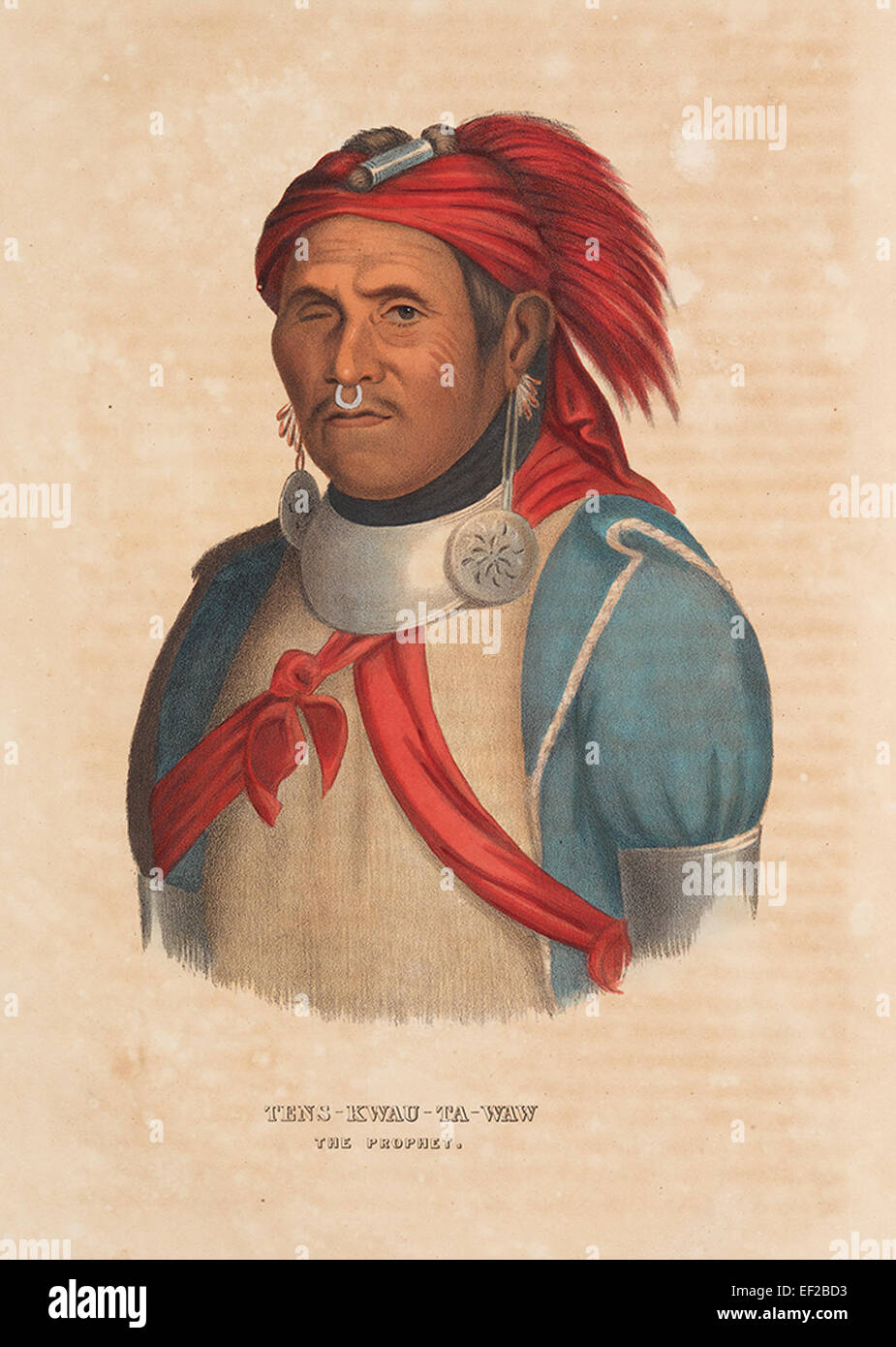

Decades later, in the early 19th century, another towering prophetic figure emerged: Tenskwatawa, the Shawnee Prophet. Born Lalawethika, he suffered from a physical disability and was initially considered an outcast. However, after a transformative experience in 1805 – a death-like trance during which he claimed to have visited the spirit world and met the Master of Life – he was reborn as Tenskwatawa, "The Open Door," a prophet with a powerful message of spiritual and moral regeneration.

Tenskwatawa’s prophecies were a direct response to the escalating pressures of American expansion and the debilitating effects of alcohol among Indigenous communities. He preached a strict moral code: sobriety, fidelity, communal ownership of land, and a rejection of American goods, customs, and Christianity. He declared, "The Great Spirit has given me power over the diseases, and I will cure all of you who will believe in me." His visions promised a return to a golden age if his followers adhered to his teachings, and warned of dire consequences if they continued to embrace American ways.

His charisma and seemingly miraculous powers (including accurately predicting a solar eclipse in 1806, which he claimed was a sign from the Great Spirit) drew thousands of followers from various tribes – Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandot, Potawatomi, Kickapoo, and others – to his settlement at Prophetstown on the Tippecanoe River. Tenskwatawa’s spiritual leadership was inextricably linked with the political and military efforts of his elder brother, the legendary warrior Tecumseh. While Tecumseh forged a pan-Indian confederacy through diplomacy and military strategy, Tenskwatawa provided the spiritual foundation, unifying diverse peoples under a shared vision of cultural purity and resistance. Their combined efforts posed the most significant Indigenous challenge to American expansion in the Old Northwest, culminating in the War of 1812. Though Prophetstown was destroyed in the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, and Tecumseh was killed in 1813, the Tenskwatawa-Tecumseh movement stands as a powerful testament to the combined force of prophetic vision and political action in the colonial era.

While Neolin and Tenskwatawa focused heavily on outright rejection and resistance, another significant prophet, Handsome Lake (Ganioda’yo) of the Seneca Nation (Haudenosaunee Confederacy), offered a path of cultural revitalization through moral reform and strategic adaptation. In 1799, Handsome Lake, a former warrior and an alcoholic, experienced a series of visions after falling gravely ill. His visions, which he shared upon his recovery, formed the basis of the "Good Message" or Gaiwiio, a comprehensive code of conduct that continues to guide many Haudenosaunee today.

Handsome Lake’s message was both conservative and revolutionary. He condemned the consumption of alcohol, witchcraft, abortion, and other perceived moral failings that he believed contributed to the decline of his people. He advocated for strong family units, respect for elders, and the importance of traditional ceremonies. However, unlike Neolin or Tenskwatawa, Handsome Lake also recognized the need for some degree of accommodation with the changing world. He encouraged his people to adopt certain aspects of European farming techniques, build log cabins, and even send their children to missionary schools, provided these changes did not compromise core Haudenosaunee values. His message was not one of complete rejection, but of selective adaptation – a way to preserve cultural integrity and sovereignty in a profoundly altered landscape.

The "Good Message" provided a framework for social and spiritual stability during a period when the Haudenosaunee had lost much of their land and faced immense pressure to assimilate. It offered a means for the Seneca and other Haudenosaunee nations to navigate the complexities of coexistence with American society while strengthening their internal cohesion and cultural identity. Handsome Lake’s legacy is a powerful example of how prophetic movements could foster resilience and cultural survival through internal reform, demonstrating that resistance could take many forms beyond direct military confrontation.

The role of these Native American prophets during the colonial era was multifaceted and profound. They acted as spiritual guides, offering solace and meaning in times of unparalleled suffering. They were moral reformers, striving to heal communities ravaged by new diseases and social ills. They were cultural preservers, fighting to maintain traditional languages, ceremonies, and ways of knowing. And crucially, they were political unifiers, using their spiritual authority to forge alliances and inspire resistance against the encroaching colonial powers.

Their movements, though ultimately unable to halt the tide of colonization, left an indelible mark. They preserved Indigenous languages, ceremonies, and worldviews that might otherwise have been lost. They instilled a sense of collective identity and purpose that transcended tribal boundaries, laying the groundwork for future pan-Indian movements. Moreover, their prophecies and teachings continue to resonate today, serving as powerful reminders of Indigenous resilience, self-determination, and the enduring strength of spiritual traditions in the face of adversity.

In a period often characterized by military defeats and land cessions, these prophets represented an unseen war for the soul of Indigenous America. They fought not just for territory, but for cultural integrity, spiritual freedom, and the right to define their own destiny. Their voices, echoing through the centuries, remind us that resistance to oppression is not always waged on battlefields, but often in the sacred spaces of the heart and mind, guided by visions of a better, more sovereign future.