The Unseen Architects: Interpreters and the Shifting Sands of Colonial Negotiations

In the grand, often brutal, theatre of colonial expansion, where empires clashed with indigenous sovereignties, land was carved up, and destinies irrevocably altered, the interpreter stood as a seemingly neutral conduit. Yet, far from being mere mouthpieces, these linguistic navigators were often the unseen architects of history, holding immense, often unacknowledged, power. They were the linchpins in negotiations that determined the fate of continents, cultural brokers caught between worlds, and sometimes, unwitting or deliberate agents of profound injustice. Their role, frequently overlooked in grand historical narratives, was nothing short of pivotal in shaping the colonial landscape.

Colonial encounters were fundamentally predicated on a vast chasm of understanding, not just of language but of worldviews, legal systems, and societal structures. European powers arrived with concepts of land ownership, sovereignty, and treaty law that were often alien to indigenous peoples, whose relationships with land were frequently communal, spiritual, and based on stewardship rather than individual proprietorship. Bridging this chasm fell squarely on the shoulders of interpreters – individuals who, by virtue of their linguistic prowess, became indispensable.

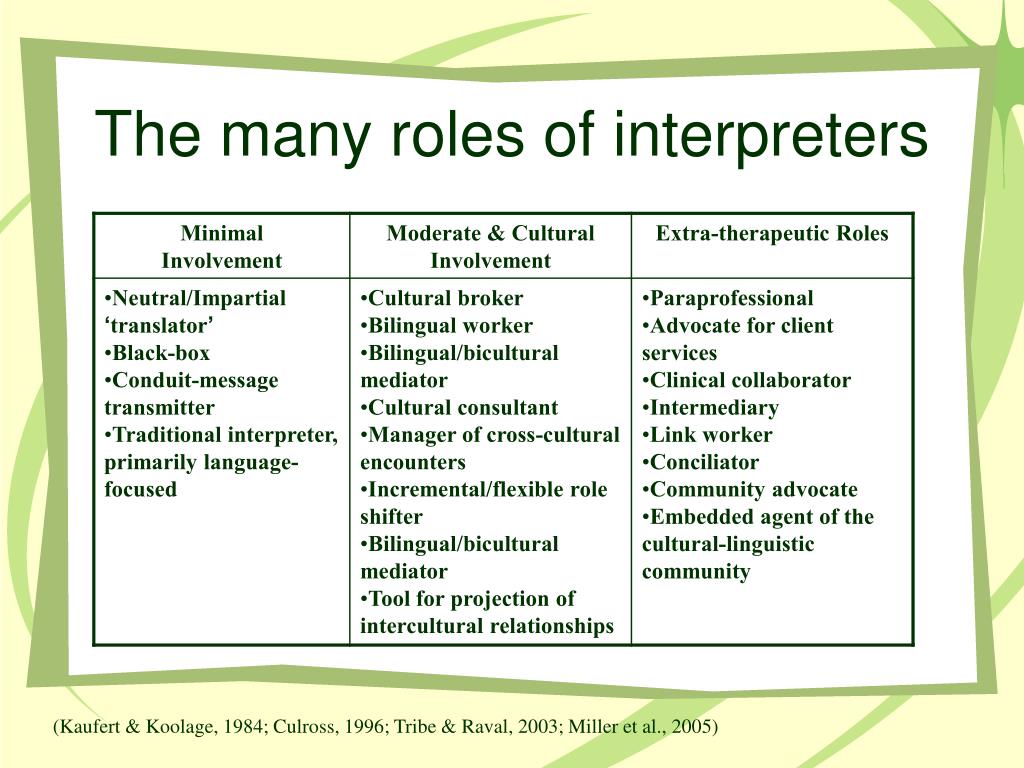

These interpreters were a diverse group: sometimes indigenous individuals who had learned European languages through prior contact, trade, or capture; sometimes Europeans who had lived among indigenous communities; and occasionally, individuals of mixed heritage. Their unique position afforded them a dangerous degree of agency. They were not just translating words; they were translating concepts, intentions, and worldviews. This act of translation was never a neutral, one-to-one exchange, particularly when dealing with terms like "sovereignty," "cession," "ownership," or "peace."

Consider the profound implications of translating "land ownership." For many indigenous cultures, the idea of "owning" land in the European sense – a transferable commodity that could be bought, sold, and exclusively possessed – was incomprehensible. Land was often seen as sacred, a source of life, to be respected and shared, not a possession. An interpreter tasked with conveying a European demand for "cession of land" might struggle to find an equivalent concept, potentially simplifying or misrepresenting the demand in a way that seemed innocuous to indigenous leaders but was legally binding and devastating in the European context.

One of the most stark and well-documented examples of this linguistic chasm and the interpreter’s crucial role is the Treaty of Waitangi, signed in 1840 between the British Crown and various Māori chiefs in New Zealand. The treaty, intended to establish British sovereignty while protecting Māori rights, exists in two versions: English and Māori. The discrepancies between these versions, largely attributed to the challenges of translation, have fueled debate and conflict for nearly two centuries.

The English version of the treaty stated that Māori chiefs ceded "all the rights and powers of Sovereignty" to the Queen. However, the Māori version, translated by missionary Henry Williams and his son Edward, used the word "kawanatanga" for sovereignty. "Kawanatanga" derived from "governor," a term Māori had become familiar with, and implied a delegation of governance or administration, not an absolute surrender of their inherent authority. For Māori, their own absolute authority, or "rangatiratanga," over their lands, resources, and people, remained intact. They believed they were entering a partnership, not submitting to absolute rule.

This fundamental difference, facilitated by the interpretation, meant that both parties signed the same document with vastly different understandings of its implications. For Māori, it was about sharing power; for the British, it was about acquiring dominion. The enduring legacy of this misinterpretation led to decades of land wars, dispossession, and a profound sense of betrayal among Māori, illustrating how an interpreter’s choices, even if made with the best intentions, could have cataclysmic consequences.

The interpreter’s position was fraught with ethical dilemmas and personal risk. They often found themselves caught between the demands of powerful colonial authorities and the expectations of their own communities. Their loyalty was constantly tested. Were they primarily serving the colonial power, from whom they might gain prestige, material wealth, or even protection? Or were they subtly working to protect their own people, attempting to mitigate the damage of negotiations they knew were inherently unbalanced?

In some cases, interpreters leveraged their unique position for personal gain. They could deliberately mistranslate to benefit themselves, acquiring land, trade advantages, or political influence. Historian Philip D. Curtin, in "The Image of Africa," notes how coastal African interpreters, often the first point of contact, could control access to the interior, shape perceptions, and dictate the terms of trade, acting as powerful intermediaries who amassed significant wealth and power.

Conversely, some interpreters actively sought to protect indigenous interests, attempting to subtly shift the meaning of words to avoid the most damaging clauses, or to alert their own people to impending dangers. These acts of resistance were often clandestine, carried out under the watchful eyes of colonial officials. Their stories are harder to recover, as their contributions were often deliberately obscured or dismissed by colonial records.

The linguistic challenges extended beyond specific words. The very structure of communication differed. European negotiations were often formal, written, and legally binding, culminating in documents. Many indigenous traditions relied on oral agreements, ceremony, and shared understanding, where a signature on a piece of paper held little inherent meaning compared to the spoken word and the shared ritual of agreement. An interpreter had to navigate these fundamental differences, often failing to convey the gravity of European legalism or the nuanced importance of indigenous ceremonial protocols.

In North America, the vast number of treaties signed between European powers (and later the United States and Canada) and Indigenous nations similarly hinged on interpreters. The concept of "selling" land was often misunderstood as granting temporary use rights or sharing access, rather than a permanent alienation of territory. Indigenous leaders, when signing away vast tracts, often believed they were agreeing to coexist, share resources, or grant passage, not to relinquish their ancestral lands forever. The interpreter’s role in conveying these deeply divergent concepts of land tenure was critical, and often tragically flawed. Historian Richard White, in "The Middle Ground," highlights how interpreters and cultural brokers were essential in creating spaces of mutual understanding, however fragile, but also how these spaces were inherently unstable and prone to manipulation.

The consequence of these interpreted negotiations has been profound and enduring. Land dispossession, the erosion of indigenous sovereignty, the destruction of cultural practices, and ongoing legal battles over treaty rights are all rooted, in part, in the linguistic and conceptual gaps that interpreters were tasked with bridging. The "unseen architects" laid foundations that, intentionally or not, often favored the colonial power, setting in motion centuries of injustice.

Today, as societies grapple with the legacies of colonialism, there is a growing recognition of the interpreter’s complex and powerful role. Historians are increasingly scrutinizing colonial archives not just for what was said, but for how it was said, who said it, and who translated it. This critical examination sheds light on the agency of these linguistic intermediaries, acknowledging their capacity to influence outcomes, whether through deliberate manipulation, cultural brokerage, or simply the immense difficulty of translating between radically different worlds.

In conclusion, the interpreters in colonial negotiations were far more than neutral linguistic tools. They were active participants, cultural brokers, and sometimes unwitting accomplices in the grand project of empire. Their unique position at the nexus of power, language, and culture gave them an extraordinary, often unrecorded, capacity to shape history. Their decisions, their biases, their struggles, and their very presence were integral to the colonial encounter, laying the groundwork for the world we inhabit today – a world still reckoning with the profound and often tragic consequences of words exchanged, or perhaps, fundamentally misunderstood. Their stories remind us that in the delicate art of communication, especially across vast cultural divides, the conduit is never truly invisible.