Echoes of the Red River: The Plains Tribes’ Last Stand

In the vast, untamed heart of the American Great Plains, where the wind whispered through endless tallgrass and the thundering hooves of buffalo once dictated the rhythm of life, a final, desperate chapter unfolded. The Red River War of 1874-1875 was not merely a series of battles; it was the tragic crescendo of a century-long clash between two irreconcilable visions of America: the nomadic freedom of the Plains tribes and the relentless westward expansion of the United States. It marked the definitive end of a way of life that had sustained the Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho for generations, forcing them onto reservations and into an unfamiliar world.

To understand the Red River War is to delve deep into the rich, complex tapestry of Plains tribes’ history, a narrative steeped in a profound connection to the land, an intricate social structure, and a fierce independence. For centuries, these equestrian cultures had thrived, their existence inextricably linked to the American bison. The buffalo was not just food; it was their supermarket, their hardware store, their spiritual guide, providing meat, hide for tipis and clothing, bones for tools, and sinew for thread. Their society was built around the hunt, their spiritual beliefs infused with the buffalo’s essence, and their nomadic movements dictated by the herds’ migrations.

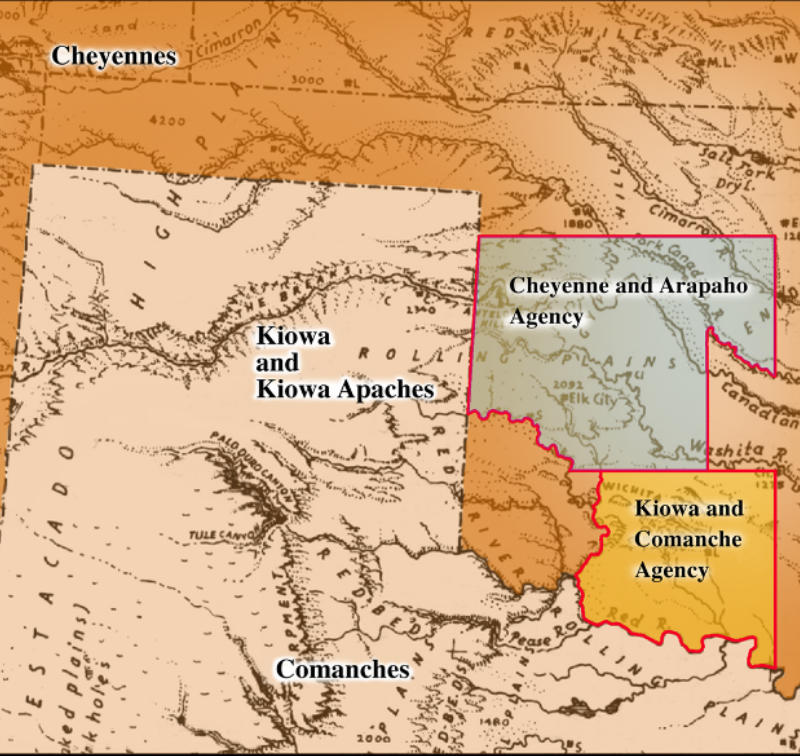

However, by the mid-19th century, this ancient way of life was under siege. The inexorable march of American settlers, fueled by Manifest Destiny and the allure of land and resources, pushed ever westward. Treaties, often signed under duress or misunderstood, became mere "paper promises," as many Native leaders called them, quickly broken by the United States government as soon as gold was discovered or new lands were coveted. The Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867, intended to confine the Comanche, Kiowa, and Southern Cheyenne to reservations in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), proved largely ineffectual. While some bands, weary of conflict and starvation, attempted to adapt, others, particularly the more traditional and defiant factions, saw it as an unacceptable curtailment of their freedom and a betrayal of their ancestral lands.

The most devastating blow, however, came from the systematic slaughter of the buffalo. What began as sport and sustenance for settlers quickly escalated into a deliberate, government-sanctioned policy designed to cripple the Plains tribes. Railroads brought professional hunters, and within a few short years, millions of buffalo were decimated, their carcasses left to rot, their hides shipped east. General Philip Sheridan, a key architect of the Red River War strategy, famously remarked, "Let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffalo is exterminated, as it is the only way to bring lasting peace and allow civilization to advance." This chillingly effective strategy cut the very lifeline of the Plains tribes, leaving them starving and desperate, their spiritual and physical world collapsing around them.

By the early 1870s, the simmering tensions reached a boiling point. Raids by frustrated warriors, often in retaliation for settler encroachments or treaty violations, were met with increasingly punitive responses from the U.S. Army. The winter of 1873-1874 was particularly harsh, and with buffalo herds dwindling to critical levels, hunger became a constant companion. A young Comanche warrior named Quanah Parker, son of a Comanche chief and a captured white woman, Cynthia Ann Parker, emerged as a prominent leader, advocating for a return to traditional ways and a final stand against the invaders.

The spark that ignited the Red River War came in June 1874, at the Second Battle of Adobe Walls. A group of several hundred Comanche, Kiowa, and Cheyenne warriors, led by Quanah Parker and Isa-tai, a Comanche medicine man who promised spiritual protection from bullets, attacked a buffalo hunters’ camp in the Texas Panhandle. The hunters, armed with powerful long-range rifles, were caught off guard but managed to fortify their position. Despite repeated charges and fierce fighting, the warriors were repelled, suffering significant casualties. The defeat, especially after Isa-tai’s assurances, shattered morale and fueled a desire for revenge among many, pushing the tribes further into open conflict.

The U.S. Army, under the command of General Sheridan, seized upon Adobe Walls as justification for a full-scale offensive. Their strategy, honed during previous campaigns against Native Americans, was one of "total war": relentless pursuit, winter campaigns to deny the tribes shelter and sustenance, and the systematic destruction of their resources. Five converging columns of troops, totaling over 3,000 soldiers, were dispatched from different directions to sweep the Texas Panhandle and force the tribes onto reservations. Among the prominent commanders were Colonel Ranald S. MacKenzie, Colonel Nelson A. Miles, and Colonel George Buell.

The Army’s tactics were brutal but effective. They targeted not just warriors but also their camps, destroying tipis, food stores, and, most crucially, horses. Horses were the lifeblood of the Plains tribes – essential for hunting, travel, and warfare. Without them, their nomadic existence was impossible. The winter campaigns were particularly devastating. The troops pursued the tribes through blizzards and freezing temperatures, giving them no respite, no time to hunt or gather, no chance to recover. "The only way to end the Indian Wars," Sheridan famously declared, "is to destroy their ability to make war."

One of the most decisive engagements of the war was the Battle of Palo Duro Canyon in September 1874. Colonel MacKenzie, leading elements of the 4th U.S. Cavalry, surprised a large encampment of Comanche, Kiowa, and Cheyenne in their winter refuge deep within the canyon. The warriors, believing the canyon offered impenetrable protection, had their guard down. MacKenzie’s troops descended the steep walls, scattering the encampment. While many warriors and their families managed to escape, MacKenzie’s forces captured and destroyed an estimated 1,400 horses and all their winter supplies. The destruction of their horse herds was a catastrophic blow, effectively immobilizing the tribes and robbing them of their mobility and power.

The relentless pressure, coupled with starvation, exposure, and dwindling hope, began to break the tribes’ will to resist. Bands started to surrender in small groups throughout late 1874 and early 1875, trekking to the agencies, their spirits broken, their bodies emaciated. Quanah Parker, recognizing the futility of further resistance, led his band of Kwahadi Comanche in a poignant surrender in June 1875, marking the official end of the Red River War. With his surrender, the last significant free-roaming band of Plains Indians laid down their arms.

The aftermath of the Red River War was a profound and tragic transformation for the Plains tribes. They were confined to reservations, their vast hunting grounds replaced by small plots of land, their traditional governance replaced by federal agents. The transition from boundless plains to confined reservations was catastrophic. Their spiritual connection to the land was severed, their buffalo-centric economy shattered. The government’s "peace policy" quickly morphed into an assimilation policy, epitomized by the phrase "kill the Indian, save the man." Children were forcibly sent to boarding schools, where their hair was cut, their native languages forbidden, and their cultural identities systematically suppressed.

Leaders like Satanta, the Kiowa orator and warrior who had been imprisoned even before the Red River War, became poignant symbols of the resistance. His eventual death in prison, whether by suicide or illness, represented the dying embers of a fiercely independent spirit. Quanah Parker, despite his initial defiance, became a powerful figure of adaptation, advocating for his people’s rights within the new paradigm, bridging the gap between two worlds.

The Red River War, though often overshadowed by other conflicts of the American West, stands as a pivotal moment in the history of the Plains tribes. It was their final, desperate stand against overwhelming odds, a poignant testament to their courage, resilience, and their deep-seated determination to preserve their way of life. While the war undeniably brought an end to open conflict and nomadic freedom, it did not extinguish the spirit or the cultural heritage of the Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Their history, marked by both triumph and tragedy, continues to resonate, reminding us of the profound cost of westward expansion and the enduring strength of indigenous peoples in the face of immense adversity. The echoes of the Red River War serve as a powerful, somber reminder of a vanished world and the irreversible changes that shaped the American West.