The Unyielding Voice: Red Cloud’s Diplomatic War for the Lakota

In the annals of American history, the figure of Red Cloud often conjures images of a fearsome warrior, a strategic military genius who outmaneuvered the United States Army in the heart of the Powder River Country. While his prowess on the battlefield is undeniable, to solely remember Red Cloud as a warrior is to overlook his profound and often unprecedented diplomatic achievements. For decades, this Oglala Lakota chief employed a sophisticated blend of military pressure, shrewd negotiation, and unwavering advocacy to defend his people’s sovereignty, land, and way of life against the relentless tide of American expansion. His story is not just one of resistance, but of a calculated, persistent diplomatic war waged with intellect as much as with arrows and rifles.

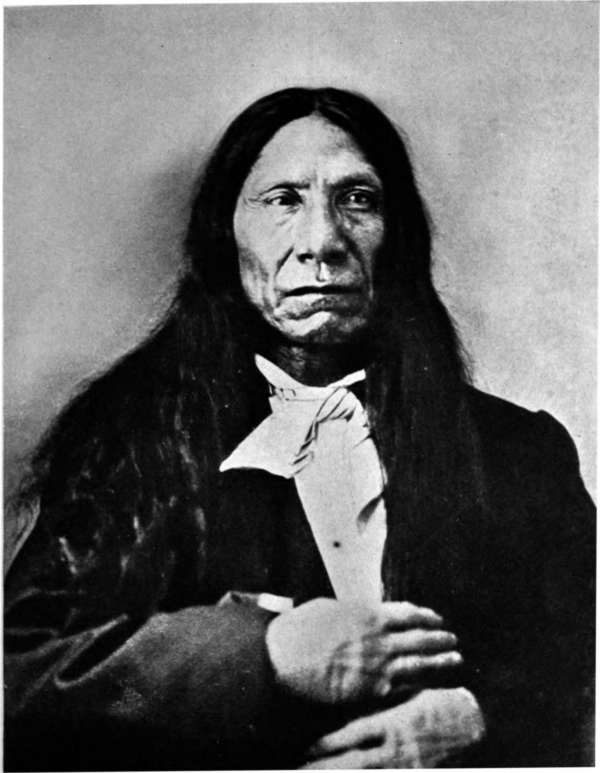

Born in 1822 near the Platte River, Red Cloud (Makhpiya Luta) came of age during a period of immense upheaval for the Lakota people. Westward expansion, fueled by the concept of Manifest Destiny, brought an ever-increasing flow of settlers, miners, and soldiers into their ancestral lands. The buffalo, cornerstone of Lakota existence, were threatened, and sacred sites were desecrated. Early treaties, often signed under duress or by unrepresentative factions, had proven to be little more than temporary expedients, consistently violated by the U.S. government. It was into this volatile environment that Red Cloud emerged not just as a leader, but as a statesman who understood that the future of his people depended on more than just military might; it required strategic engagement with the very power that sought to engulf them.

Red Cloud’s first major diplomatic triumph was born directly from military confrontation: Red Cloud’s War (1866-1868). This conflict erupted when the U.S. Army, in blatant disregard of existing treaty rights and Lakota warnings, began constructing a series of forts along the Bozeman Trail, a shortcut to the Montana goldfields that sliced directly through prime Lakota hunting grounds. Red Cloud saw this as an intolerable invasion. He rallied a coalition of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors, employing guerrilla tactics to effectively shut down the trail and besiege the forts. The most famous engagement, the Fetterman Fight in December 1866, saw over 80 U.S. soldiers annihilated, a stunning defeat that sent shockwaves through the American public and military establishment.

Crucially, Red Cloud did not just fight; he negotiated from a position of strength. His military successes forced the U.S. government to the negotiating table on Lakota terms. As the historian Robert Utley noted, "It was a war that the United States government lost, and conceded that it lost." The resulting Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868 stands as a monumental achievement in indigenous diplomacy. Under its terms, the U.S. agreed to abandon all the Bozeman Trail forts, a rare instance of a major power completely capitulating to an indigenous nation’s demands. It also established the Great Sioux Reservation, encompassing all of present-day South Dakota west of the Missouri River, and designated vast tracts of unceded hunting grounds. Red Cloud, ever the astute negotiator, famously refused to sign the treaty until the last soldier had departed from the forts, demonstrating his unwavering resolve and distrust of empty promises. His delayed signing was not a sign of hesitation, but a calculated power play, ensuring the U.S. upheld its end of the bargain before he committed his people.

The 1868 treaty was a testament to Red Cloud’s vision – a recognition that military victories could be translated into political gains. However, his diplomatic efforts did not end there. The years following the treaty were a continuous struggle to ensure its provisions were honored. In 1870, Red Cloud embarked on a landmark journey to Washington D.C., a trip that underscored his commitment to advocating for his people directly to the "Great Father." Accompanied by other Lakota leaders, he met with President Ulysses S. Grant, Secretary of the Interior Jacob Cox, and Commissioner of Indian Affairs Ely S. Parker (a Seneca himself).

This visit was a profound cultural and political experience. Red Cloud, initially awe-struck by the sheer scale and power of American civilization, quickly regained his composure and asserted his people’s rights with powerful eloquence. He found himself confronted with conflicting interpretations of the treaty, particularly regarding the boundaries of the reservation and the provisions for annuities and supplies. In a tense meeting with Secretary Cox, Red Cloud was told that the previous year’s treaty had designated the White River as the northern boundary of their territory, rather than the true Laramie boundary. Red Cloud, incensed, rose and declared, “My friends, I have left my women and children, and I have come here to the Great Father, hoping that I can get justice for them, and I have found none.” He pounded his chest and continued, "I was born a Lakota, and I am a Lakota. God Almighty made us, and He made us free."

He spoke passionately about the broken promises, the dwindling buffalo, and the plight of his people. He famously challenged President Grant and the assembled officials: "You have taken our land and our game, and we have nothing left… When the Great Father makes a treaty, he should keep it." His directness, courage, and refusal to be intimidated by the grandeur of Washington made a significant impression. While not all his demands were met, his visit brought national attention to the Lakota’s grievances and forced U.S. officials to publicly address their treaty obligations. It also offered Red Cloud a sobering glimpse into the overwhelming power of the United States, shaping his future diplomatic strategies towards adaptation and persistent, though often frustrating, advocacy within the system.

Back on the reservation, Red Cloud continued his diplomatic efforts, often clashing with corrupt Indian agents and government officials who routinely diverted resources meant for his people. He tirelessly championed education, farming, and other means of adapting to the changing world, even as he fought to preserve Lakota identity and customs. His pragmatic approach sometimes put him at odds with other Lakota leaders, such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, who opted for continued armed resistance. Red Cloud, having seen the might of Washington firsthand, understood the futility of perpetual warfare against an industrial power. His was a strategy of sustained political pressure, of holding the U.S. government accountable to its own laws and treaties.

However, the tide of Manifest Destiny proved too strong. The discovery of gold in the Black Hills in 1874, a sacred area explicitly protected by the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, unleashed a new wave of encroachment. Despite Red Cloud’s fervent protests and appeals to the treaty, the U.S. government effectively ignored its obligations, leading to the Great Sioux War of 1876 and the ultimate cession of the Black Hills. This period marked a profound defeat for Red Cloud’s diplomatic approach, demonstrating the inherent weakness of treaties when confronted by overwhelming greed and power.

Even after the final defeat of the Lakota and their confinement to reservations, Red Cloud never ceased his diplomatic efforts. He continued to advocate for his people’s rights to land, resources, and cultural preservation well into his old age. He served on various tribal councils, corresponded with government officials, and used his influence to protect his community from further exploitation. His life on the Pine Ridge Reservation, where he passed away in 1909, was a testament to his enduring commitment.

Red Cloud’s legacy as a diplomat is complex and profound. He was a leader who understood the necessity of both military power and political negotiation. He was willing to fight fiercely for his people’s rights, but also possessed the foresight to engage with his adversaries at the negotiating table. The Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868 stands as a monumental, if ultimately temporary, victory for indigenous sovereignty, a direct result of his strategic genius. His unwavering voice in Washington D.C. served as a powerful reminder of the human cost of broken promises.

In his later years, Red Cloud famously lamented, "They made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they never kept but one; they promised to take our land, and they took it." This poignant statement encapsulates the tragedy of his diplomatic struggle. Yet, his efforts were not in vain. Red Cloud demonstrated that indigenous nations could, and did, engage in sophisticated diplomacy, achieving significant political victories against overwhelming odds. He laid the groundwork for future generations of Native American activists and leaders, who would continue to fight for justice, treaty rights, and self-determination, drawing inspiration from the unyielding voice of the diplomat warrior, Red Cloud.