Quechan Bird Songs: Ancient Oral Traditions and Musical Migration Maps

Along the sun-baked banks of the lower Colorado River, where the vast desert meets the life-giving waters, the Quechan people (also known as the Yuma) have for millennia cultivated a profound cultural tradition: their Bird Songs. These are not mere melodies; they are intricate oral tapestries, living archives of history, spirituality, and an unparalleled understanding of the natural world. Far from simple entertainment, Quechan Bird Songs function as complex "musical migration maps," encoding generations of ancestral knowledge, guiding listeners through both physical landscapes and the contours of their collective memory.

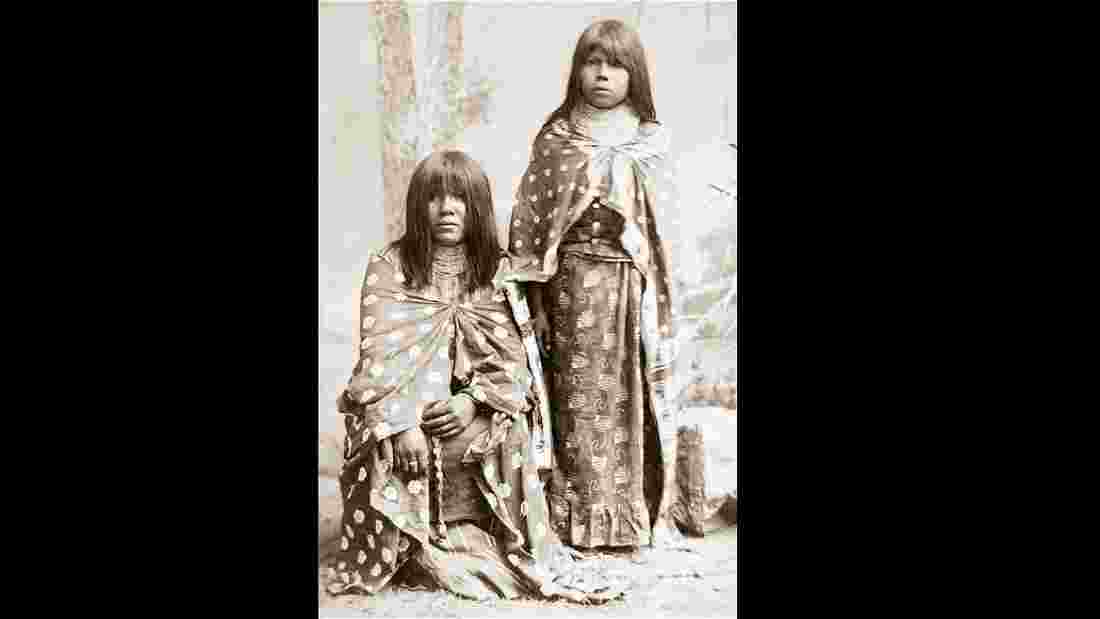

The Quechan, an Indigenous nation whose traditional lands span parts of present-day Arizona, California, and Baja California, Mexico, have endured centuries of profound change and challenge. Yet, their Bird Songs remain a vibrant testament to their resilience and the enduring power of their cultural identity. These song cycles are performed primarily by men, often in all-night gatherings, weaving together narrative, rhythm, and melody to recount the journey of creation, the movements of people and animals, and the very essence of their connection to the land.

At the heart of the Quechan Bird Songs lies a unique system of knowledge transmission. Each song cycle, often comprising hundreds of individual songs, tells a specific story or traces a particular path. For instance, a cycle might begin with the creation of the world, detail the wanderings of cultural heroes, or describe the annual movements of specific bird species. The beauty and complexity of these songs are not just in their musicality, but in the layers of information they carry. They are mnemonic devices of extraordinary power, designed to be remembered, understood, and passed down through generations with meticulous accuracy.

The concept of "musical migration maps" is central to understanding the depth of these traditions. Imagine a vast, intricate map, not drawn on parchment but etched into the very fabric of sound. As a singer progresses through a cycle, the lyrics and melodic shifts guide the listener through geographical landmarks: mountains, rivers, specific springs, and ancient campsites. More than just physical locations, the songs embed information about the flora and fauna encountered along these routes. A particular melody might describe the unique call of a specific bird, while the accompanying lyrics detail its migratory patterns, its preferred nesting sites, or even its significance as a food source or spiritual messenger.

"These songs are our libraries," one elder might explain. "They tell us where the water is, where the good plants grow, where our ancestors walked. They are our history books, our maps, and our prayers, all in one." This holistic approach means that a single song can simultaneously convey ethnobotanical knowledge, zoological observations, historical narratives, and spiritual insights. The rhythm might mimic the gait of an animal, the melody might echo the wind through a canyon, and the lyrics might recount a time when the world was new.

The emphasis on "Bird Songs" is particularly telling. Birds, with their ability to traverse vast distances, their distinct calls, and their often-predictable migratory patterns, hold immense significance for many Indigenous cultures. For the Quechan, birds are not just subjects of observation; they are teachers, guides, and often symbolic representations of spiritual journeys or aspects of creation. The songs often mimic bird calls, weaving these natural sounds into the human vocalizations, creating a seamless connection between the human and natural worlds. This deep observational knowledge allowed ancestral Quechan to anticipate seasonal changes, locate vital resources, and navigate their expansive territories with precision. The movements of cranes, the arrival of swallows, or the unique song of a desert thrasher could all be encoded within a song cycle, providing critical information for survival and cultural continuity.

The learning process for Quechan Bird Songs is rigorous and lifelong. Young men who aspire to become singers apprentice themselves to elders, spending years, even decades, memorizing vast repertoires. This involves not only learning the lyrics and melodies but also understanding the intricate narratives, the proper sequence of songs within a cycle, and the cultural context of each piece. It’s an immersive education that demands dedication, discipline, and a deep reverence for the tradition. The transmission is overwhelmingly oral, relying on direct instruction and repeated exposure, fostering an unbroken chain of knowledge stretching back into antiquity.

However, like many Indigenous oral traditions worldwide, Quechan Bird Songs face significant challenges in the modern era. The forces of assimilation, the impact of colonialism, the loss of language, and the decreasing number of fluent speakers and active singers threaten the continuity of these invaluable cultural treasures. The passing of elders who hold vast repositories of these songs represents an irreplaceable loss of knowledge. Each lost singer is akin to a library burning, taking with them unique perspectives and vital information that cannot be easily recovered.

In response to these threats, the Quechan community, often in collaboration with sympathetic academics and cultural institutions, has embarked on vital preservation efforts. These initiatives include documenting the songs through audio and video recordings, creating archival materials, and, most importantly, establishing programs to teach younger generations. Culture camps, apprenticeship programs, and community gatherings are designed to reignite interest and facilitate the intergenerational transfer of this sacred knowledge. The goal is not merely to preserve the songs as artifacts but to ensure they remain living, breathing traditions, performed and understood by future generations.

The revival of Bird Songs is more than just cultural preservation; it’s an act of sovereignty and a reaffirmation of identity. It’s about ensuring that the unique Quechan worldview, their deep connection to the land, and their ancestral wisdom continue to inform and enrich their community. The songs offer not only a link to the past but also a guide for the future, teaching principles of environmental stewardship, community responsibility, and spiritual harmony that are profoundly relevant in today’s world.

Ultimately, Quechan Bird Songs stand as a powerful testament to the sophistication and depth of Indigenous oral traditions. They are far more than beautiful music; they are intricate mnemonic devices, cultural compasses, and living archives that map the very essence of a people’s journey through time and space. As the sun rises over the Colorado River, and the echoes of these ancient songs reverberate through the desert air, they remind us of the enduring power of human memory, the profound wisdom embedded in the natural world, and the vital importance of protecting these irreplaceable voices from the past, present, and future. Their continued existence is a beacon of cultural resilience, a testament to the fact that some of the most powerful maps are not drawn on paper, but sung into being.