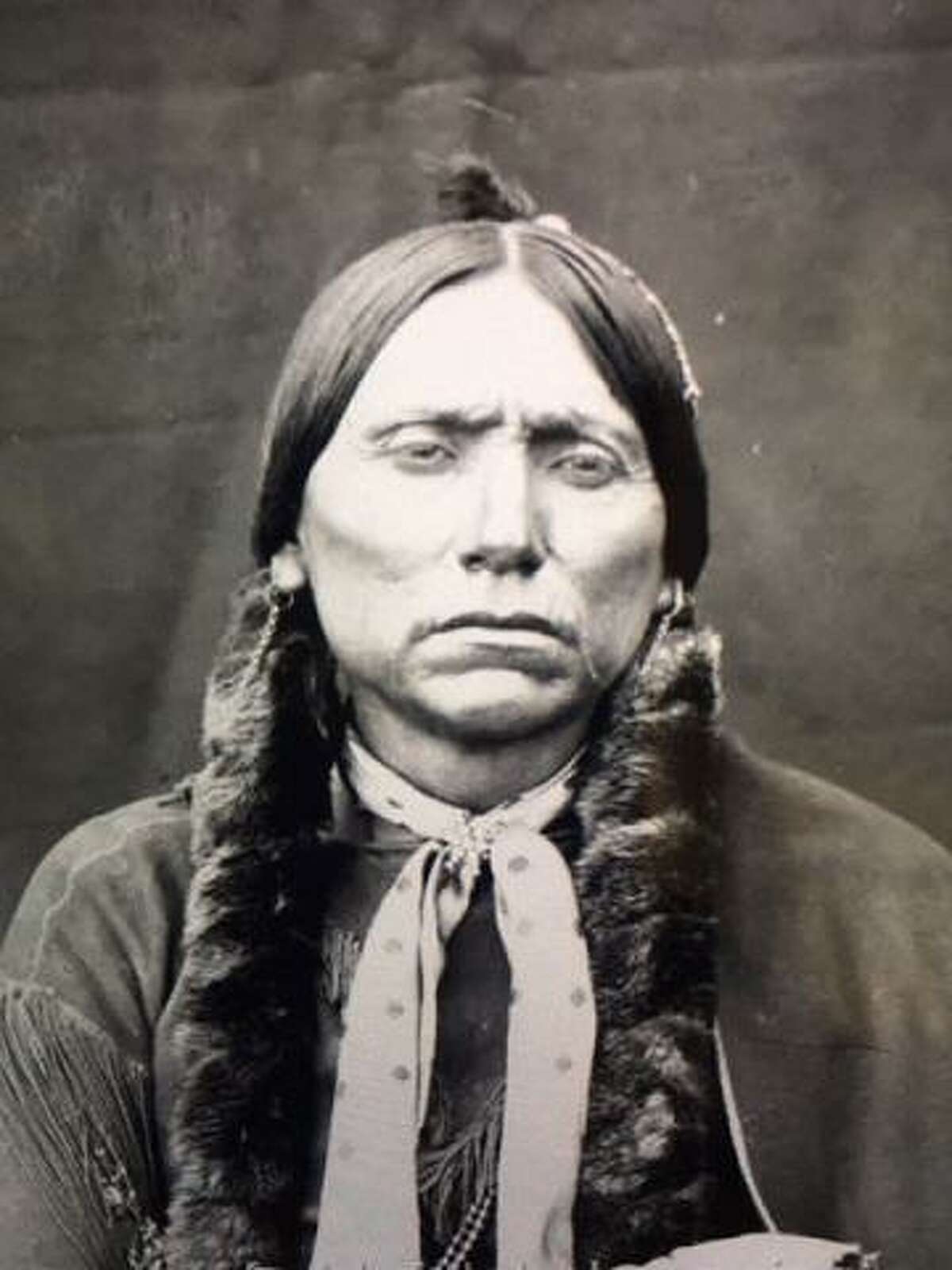

Quanah Parker: The Last Warrior, The First Statesman of the Comanche Nation

In the vast, untamed expanse of the 19th-century American West, where cultures clashed and empires were forged and shattered, one figure emerged who embodied the very essence of this tumultuous era: Quanah Parker. Born of two worlds, a formidable warrior, and later a visionary leader, Parker navigated the treacherous currents of his time with an unparalleled blend of ferocity, wisdom, and adaptability. His life story is not merely a chapter in Native American history, but a profound narrative of survival, transformation, and the enduring spirit of a people caught between the relentless march of manifest destiny and the sacred traditions of their ancestors.

Quanah Parker’s lineage itself was a testament to the complex tapestry of the frontier. Born around 1845-1852, his mother was Cynthia Ann Parker, a white settler girl captured by Comanches at the age of nine during the Fort Parker raid in 1836. She fully assimilated into the Kwahadi Comanche band, married Chief Peta Nocona, and bore him three children, one of whom was Quanah. His father, Peta Nocona, was a renowned warrior and leader, instilling in his son the fierce independence and equestrian mastery that defined the "Lords of the South Plains." This unique heritage – a white mother, a powerful Comanche father – positioned Quanah from birth as a bridge between two seemingly irreconcilable worlds, a role he would ultimately embrace with profound consequence.

The Comanche, at the zenith of their power, controlled a vast dominion stretching from the Arkansas River to northern Mexico, a territory they fiercely defended against all intruders. They were nomadic, buffalo-hunting people, their lives inextricably linked to the thundering herds that provided sustenance, shelter, and tools. Their horsemanship was legendary, their fighting prowess unmatched. Quanah grew up immersed in this warrior culture, learning to ride, hunt, and fight from an early age. His formative years were marked by constant skirmishes with rival tribes, Texas Rangers, and the encroaching white settlers who increasingly threatened the Comanche way of life.

As the buffalo herds dwindled under the relentless hunting of white frontiersmen and the pressure from the U.S. Army mounted, the Comanche’s existence became increasingly precarious. The Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 attempted to confine the Comanches to a reservation, but many, including Quanah and his Kwahadi band, refused to comply. They held fast to their freedom and their ancestral lands. It was during this period of escalating conflict that Quanah rose to prominence as a war chief, known for his strategic acumen and unwavering courage. He quickly earned a reputation as one of the most defiant and effective leaders against the encroaching white forces.

One of the defining moments of Quanah’s warrior career was the Second Battle of Adobe Walls in June 1874. Leading a coalition of Comanche, Cheyenne, and Kiowa warriors, Quanah spearheaded an attack on a buffalo hunters’ camp in the Texas Panhandle. Though the Native American forces were ultimately repelled by the hunters’ long-range rifles, Quanah’s leadership in the engagement cemented his status as a formidable war chief. This battle, however, proved to be a harbinger of the end of the Plains Indian Wars. The U.S. government responded with the Red River War, a relentless campaign aimed at crushing Native American resistance and forcing them onto reservations. With their primary food source, the buffalo, systematically exterminated, and facing a harsh winter without supplies, the remaining free Comanches were starved into submission.

In 1875, facing overwhelming odds and the decimation of his people, Quanah Parker made the agonizing decision to surrender at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. It was the end of an era, the last of the Comanche chiefs bringing his people into a new, uncertain world. The transition to reservation life was traumatic for the proud Comanches, stripping them of their freedom, their hunting grounds, and their traditional way of life. Yet, it was in this crucible of cultural upheaval that Quanah Parker demonstrated his most extraordinary leadership qualities.

Rather than succumb to despair, Quanah embraced his new reality with a pragmatic vision for his people’s survival. He recognized that the old ways were gone forever, and that adaptation was the only path forward. He embarked on a remarkable transformation from fierce warrior to astute statesman, becoming the primary intermediary between the Comanche people and the U.S. government. He quickly learned English, though he often used interpreters, and tirelessly advocated for his people’s rights within the new system. He understood the power of education, encouraging his people to send their children to schools. He promoted cattle ranching, teaching his people the skills necessary for economic self-sufficiency, even negotiating land leases with white ranchers, often securing favorable terms for his tribe.

Quanah’s ability to bridge two cultures was perhaps best exemplified by his famous "Star House" built near Cache, Oklahoma. This large, two-story Victorian home, complete with a porch and a star painted on the roof, was a unique blend of Anglo-American architecture and Comanche sensibility. It housed his multiple wives (he adhered to traditional Comanche polygamy, though it was frowned upon by white society) and served as a hub for tribal meetings, a testament to his continued leadership and his efforts to maintain Comanche identity amidst assimilation pressures.

Beyond his political and economic efforts, Quanah also became a prominent spiritual leader. He played a crucial role in the development and spread of the peyote religion, which evolved into the Native American Church. He saw peyote as a means for his people to maintain their spiritual identity and find solace and healing in a time of immense cultural dislocation. His leadership in this movement provided a crucial anchor for many Native Americans struggling with the loss of their traditions. "The white man goes into his church and talks about God," Quanah is often quoted as saying. "The Indian goes into his teepee and talks to God." This spiritual resilience, championed by Quanah, became a powerful force for cultural preservation.

Quanah Parker’s influence extended far beyond the reservation. He forged unlikely friendships with powerful white figures, including cattle baron Charles Goodnight and even President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt, an avid hunter, visited Quanah at his Star House in 1905, seeking his guidance for a wolf hunt. This interaction showcased Quanah’s remarkable ability to command respect and exert influence across racial and cultural lines. He frequently traveled to Washington D.C., meeting with presidents and government officials, tirelessly lobbying for his people’s interests. He was a master negotiator, able to speak the language of both the Comanche council fire and the American political arena.

Quanah Parker died on February 23, 1911, at his Star House, and was buried at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. His death marked the end of an extraordinary life, a journey from the free-ranging plains of the Comanche Empire to the halls of power in Washington D.C. He was a man who, against all odds, guided his people through one of the most traumatic periods in their history. He was the last warrior chief of the Comanche, but also their first great statesman, demonstrating that true leadership lies not just in defending the past, but in courageously forging a path to the future.

Quanah Parker’s legacy endures as a powerful symbol of resilience, adaptation, and the complex interplay of cultures in the American West. He was a figure of profound contradictions and remarkable synthesis – a fierce defender of his heritage who understood the necessity of change, a warrior who became a diplomat, and a man born of two worlds who ultimately built bridges between them. His story reminds us that history is rarely black and white, and that even in the face of overwhelming adversity, the human spirit, guided by visionary leadership, can find new ways to survive and thrive.