Unearthing Truth: The Enduring Power of Primary Sources in Native American History

For centuries, the narrative of Native American history has been largely sculpted by external gazes – the diaries of missionaries, the reports of military commanders, the treaties of colonizers. These accounts, while often the most readily available, are frequently tainted by bias, misunderstanding, and the inherent power dynamics of conquest. To truly comprehend the rich, complex, and resilient histories of Indigenous peoples across North America, historians and the public alike must embark on a more profound journey: one that prioritizes and critically engages with the vast, diverse, and often overlooked tapestry of primary sources generated by or pertaining directly to Native communities. This journey is not merely academic; it is an act of decolonization, a vital step towards reclaiming and honoring authentic Indigenous voices and experiences.

The challenge lies in broadening our definition of "primary source." Western historical methodology traditionally privileges written documents. However, for many Native American cultures, history was, and often still is, meticulously preserved and transmitted through oral traditions, material culture, archaeological sites, and visual records. To limit our scope to only written European accounts is to silence millennia of vibrant human experience. Understanding Native American history demands an interdisciplinary approach, one that respects and integrates all forms of historical evidence, recognizing each as a unique window into the past.

Among the earliest and most prevalent written primary sources are the colonial records. These include the Jesuit Relations, detailed annual reports from French missionaries in New France, offering ethnographic observations alongside religious proselytization. Similarly, the journals of explorers like Lewis and Clark, military dispatches, government reports on "Indian affairs," and treaties negotiated between sovereign Native nations and European powers provide glimpses into interactions, perceptions, and policies. While invaluable for understanding colonial motivations and early encounters, these documents must be read with a critical eye. They reflect the colonizer’s perspective, often portraying Native peoples through lenses of "savagery" or "nobility," justifying land appropriation, and frequently misinterpreting or deliberately distorting Indigenous political structures and cultural practices. As Native American historian Devon Mihesuah argues, "To rely solely on non-Indian sources is to continue to perpetuate a colonial perspective." Yet, by carefully analyzing language, identifying underlying assumptions, and comparing these accounts with other forms of evidence, scholars can still glean vital information, sometimes even discerning glimpses of Native agency and resistance between the lines.

Crucially, Native voices did emerge in written form, even within the confines of a colonizing society. Early Native American authors, often educated in mission schools, penned autobiographies, petitions, and essays that challenged prevailing stereotypes and advocated for their people. William Apess, a Pequot minister, published A Son of the Forest in 1829, one of the first autobiographies by a Native American, offering a searing critique of American racism and hypocrisy. Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins’ Life Among the Paiutes: Their Wrongs and Claims (1883) provided a firsthand account of Paiute history, dispossession, and resilience. The Cherokee Phoenix, launched in 1828, was the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States, printed in both English and the Cherokee syllabary developed by Sequoyah. These precious documents represent direct challenges to the dominant narrative, providing an Indigenous perspective on crucial historical events and offering profound insights into cultural values, political aspirations, and the devastating impact of forced removal and assimilation policies.

However, the most profound and extensive archive of Native American history resides in their oral traditions. For millennia, stories, songs, ceremonies, and genealogies served as sophisticated systems for preserving historical memory, transmitting knowledge, and reinforcing cultural identity. These are not mere folklore; they are carefully maintained historical accounts, often passed down verbatim through generations of trained storytellers. Creation stories, migration narratives, accounts of significant battles, diplomatic agreements, and family histories constitute a living, breathing primary source. "Our stories are our theories," states Anishinaabeg scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, emphasizing that these narratives contain complex philosophical, political, and historical insights. The challenge for non-Native historians lies in respecting the integrity of these traditions, understanding their internal logic, and recognizing their validity as historical evidence, often without imposing Western linear concepts of time or causality. Engaging with contemporary Native elders and knowledge keepers, when done respectfully and ethically, offers unparalleled access to these invaluable living archives.

Beyond words, material culture provides tangible connections to the past. Archaeological findings – from ancient tools and pottery fragments to complex urban centers like Cahokia Mounds in present-day Illinois, which housed tens of thousands of people around 1200 CE – reveal sophisticated societal structures, trade networks, technological innovations, and spiritual beliefs. Sacred sites, earthworks, and petroglyphs (rock carvings) are not just remnants; they are historical markers, sometimes depicting astronomical events, migration routes, or significant cultural moments. Wampum belts, intricately woven shell beads, served as mnemonic devices for recording treaties, alliances, and historical events for Northeastern Woodlands nations, acting as living documents of diplomatic relations. The ethical considerations surrounding archaeology and the repatriation of artifacts and ancestral remains, as codified by laws like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), underscore the profound connection Indigenous peoples maintain with these material expressions of their heritage.

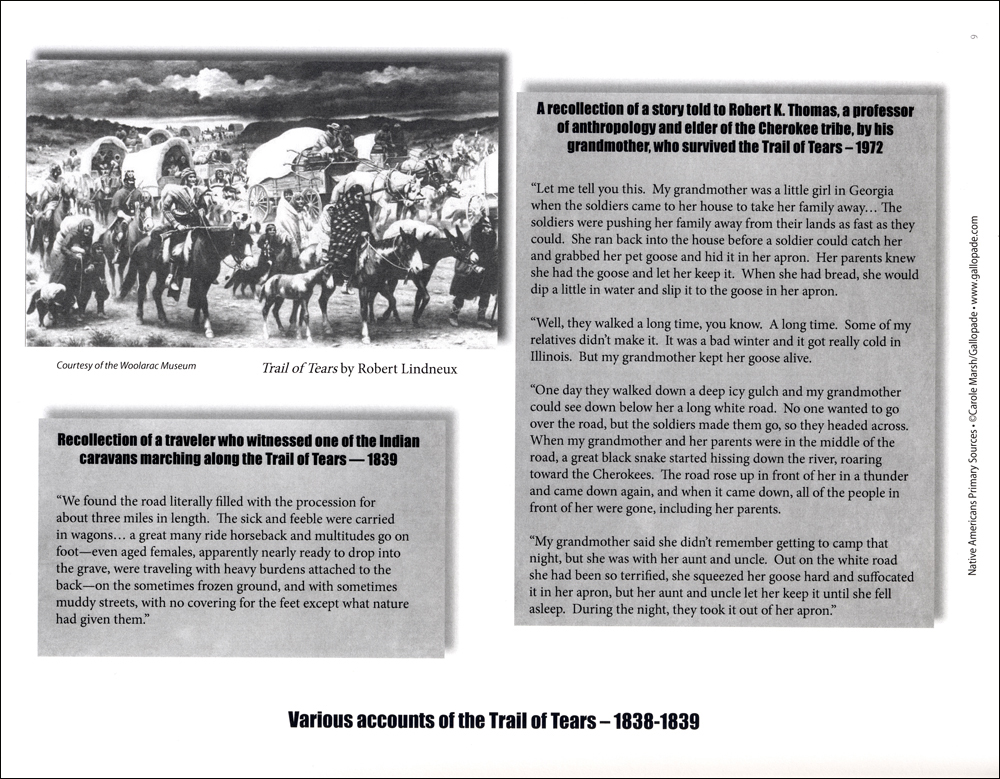

Visual primary sources also offer unique perspectives. Ledger art, developed by Plains warriors imprisoned in the late 19th century, used ledger books and drawing materials to depict battles, ceremonies, daily life, and encounters with outsiders, often from a deeply personal and Indigenous viewpoint. Pre-contact rock art and hide paintings similarly narrate historical events, spiritual journeys, and cultural practices. Early photography, while often commissioned by outsiders like Edward Curtis and frequently romanticizing or misrepresenting Native life, can still, with careful deconstruction, offer visual records of individuals, dress, and environments, especially when combined with Native commentary or contextual information. The emergence of Native photographers and filmmakers in the 20th and 21st centuries provides an increasingly authentic visual record created from within Indigenous communities.

The task of navigating these diverse primary sources is a complex one, demanding not just academic rigor but also cultural humility and ethical engagement. It requires historians to decenter colonial narratives, to listen actively to Native voices in all their forms, and to acknowledge the sovereignty of Indigenous knowledge systems. It means grappling with the biases inherent in virtually all historical records, whether colonial or Indigenous, and seeking corroboration across different types of sources. Most importantly, it necessitates a collaborative approach, working alongside Native communities, scholars, and cultural institutions to interpret and share these histories responsibly.

In conclusion, a holistic understanding of Native American history is unattainable without a comprehensive and critical engagement with its multifaceted primary sources. From the nuanced interpretations of colonial documents to the profound wisdom embedded in oral traditions, from the silent stories of archaeological sites to the vibrant narratives of ledger art, these sources collectively paint a picture of immense resilience, deep cultural sophistication, and enduring sovereignty. By prioritizing these voices and forms of evidence, we do more than simply record the past; we participate in an ongoing act of historical justice, ensuring that the true, multifaceted, and powerful stories of Native America are finally heard, understood, and honored for generations to come. The effort to unearth these truths is an ongoing journey, but one that promises a richer, more accurate, and more respectful understanding of a foundational chapter in human history.