The Invisible Highways: Unraveling the Great Plains’ Pre-Contact Trade Networks

The popular image of the Great Plains before European arrival often conjures a scene of isolated, nomadic bison hunters, living a self-sufficient existence amidst vast, untamed grasslands. While bison hunting was undeniably central to many Plains cultures, this simplistic narrative belies a far more intricate and dynamic reality. Long before the arrival of European traders and their manufactured goods, the Great Plains was crisscrossed by a sophisticated, vital, and millennia-old network of trade routes – invisible highways of exchange that connected diverse Indigenous nations across an immense continent. These networks were not mere marketplaces; they were the very arteries of cultural, economic, and social life, shaping identities, fostering diplomacy, and facilitating the flow of essential goods, knowledge, and innovation.

To understand these pre-contact trade networks is to challenge preconceived notions of Indigenous societies as static or insular. It reveals a landscape bustling with movement, negotiation, and strategic alliances, where distant resources were prized, and specialized economies intertwined. From the Rockies to the Great Lakes, and from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian Shield, goods and ideas flowed with a remarkable efficiency, driven by necessity, desire, and the enduring human impulse to connect.

The Landscape of Exchange: Why Trade Flourished

The sheer geographical and ecological diversity of the Great Plains itself was a primary catalyst for trade. The Plains were not homogenous; they encompassed distinct ecological zones, from the semi-arid shortgrass prairies of the west to the more fertile tallgrass prairies of the east, and bordered by mountains, forests, and major river systems. This diversity meant that different regions offered unique resources, creating a natural impetus for exchange.

For instance, the sedentary agricultural communities, such as the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara along the Missouri River, or the Pawnee and Wichita further south, cultivated vast fields of corn, beans, and squash. These staple crops provided a stable food supply, allowing for larger, more permanent settlements. In contrast, the more nomadic groups, often residing in the western Plains, were expert hunters of bison, providing abundant hides, meat, and bone. Neither group was entirely self-sufficient in all desired resources. The agriculturalists sought durable bison hides for tipis and clothing, and the hunters coveted the nutritional density and storage potential of cultivated crops. This complementary economy formed the bedrock of a robust trading system.

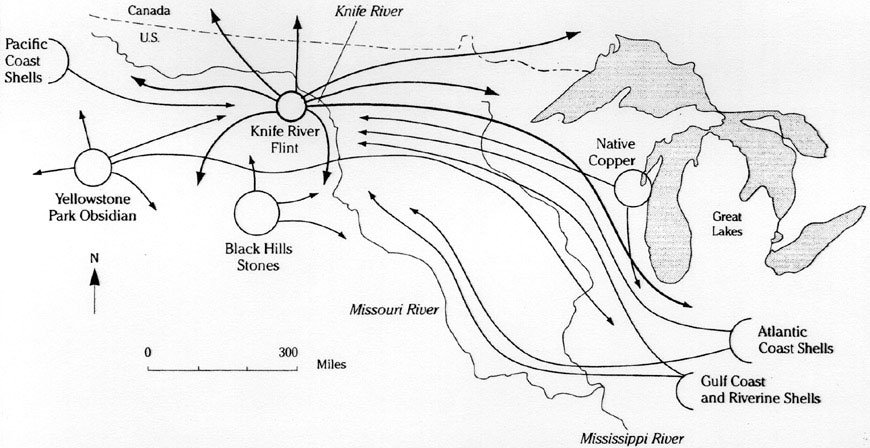

Beyond basic sustenance, specialized resources were scattered across the continent, creating a demand for long-distance trade. Obsidian, a volcanic glass prized for its sharp edges in tool and weapon making, was found primarily in the Rocky Mountains. Copper, valued for ornaments and tools, originated in the Great Lakes region. Marine shells, used for jewelry and ceremonial objects, traveled thousands of miles inland from the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific coast. Perhaps one of the most iconic trade goods was catlinite, or pipestone, a sacred red argillite used for crafting ceremonial pipes. The most significant quarry, located in what is now Pipestone, Minnesota, was considered neutral ground by many tribes, a testament to the shared spiritual significance and the need for peaceful access to this vital resource.

The Goods and Their Journeys: A Web of Desires

The catalogue of traded goods was extensive, reflecting both practical needs and cultural values:

- Foodstuffs: Dried corn, beans, squash, tobacco, wild rice, salt, medicinal herbs, pemmican (dried meat and fat).

- Raw Materials: Obsidian, chert (flint), catlinite, copper, marine shells, lignite, ochre pigments, feathers, wood (especially for bows and arrows).

- Finished Goods: Pottery, tanned hides, robes, moccasins, crafted tools, weapons (bows, arrows, spear points), jewelry, ceremonial objects.

The routes these goods traveled were not always direct. Often, items would pass through several hands, moving from one tribe to the next, like a series of interconnected relays. This system created "middleman" societies who became adept at negotiation and diplomacy. The Mandan and Hidatsa villages along the Missouri River, for example, were renowned trade hubs. Situated strategically at the confluence of several ecological zones, they served as crucial intermediaries, exchanging agricultural surpluses and pottery with nomadic groups from the west for bison products, and then trading these items further east for other goods.

"The Mandans, in particular, served as a crucial ‘entrepreneurial’ people," notes archaeologist George Frison. "Their villages were not just homes, but vibrant marketplaces where goods from hundreds, even thousands, of miles away could be found." Evidence of this long-distance exchange is abundant in archaeological digs: obsidian from Yellowstone found in Nebraska sites, Gulf Coast conch shells unearthed in South Dakota, and Great Lakes copper artifacts appearing in Kansas.

Mechanisms of Exchange: Beyond Simple Barter

Trade on the Great Plains was far more nuanced than simple bartering. It encompassed a range of practices that reflected deep social, political, and spiritual dimensions:

- Direct Exchange: Often occurred between neighboring tribes with complementary economies. A group with abundant hides would meet a group with surplus corn to directly exchange goods.

- Trade Fairs and Rendezvous: Seasonal gatherings were crucial, especially along major river systems. These were not solely economic events but also social, diplomatic, and ceremonial occasions. Tribes would gather, sometimes hundreds or thousands strong, to trade, arrange marriages, renew alliances, settle disputes, and participate in shared ceremonies. These events fostered inter-tribal peace, at least temporarily, and allowed for a wider array of goods and information to be exchanged.

- Gift-Giving: An essential component of diplomacy and alliance building. Gifts were not simply free offerings but created reciprocal obligations and cemented social bonds. A valuable gift could initiate a trade relationship, settle a conflict, or solidify a peace treaty.

- Specialized Traders: Some individuals or families might have specialized in trade, developing extensive knowledge of routes, prices, and distant peoples. They often learned multiple languages or developed a shared Plains Sign Language to facilitate communication across linguistic barriers.

The Social and Cultural Impact: Conduits for Knowledge

These trade networks were not just pathways for goods; they were conduits for culture, technology, and knowledge. As people met, negotiated, and exchanged, they also shared stories, spiritual beliefs, artistic styles, and technological innovations.

- Technological Diffusion: The spread of bow and arrow technology, pottery styles, or agricultural techniques could often be traced along trade routes. A new method for tanning hides or flint-knapping could travel across vast distances.

- Linguistic Exchange: The necessity of communication led to the development of shared sign languages, allowing diverse linguistic groups to interact effectively. Some trade jargons, simplified versions of specific languages, also emerged.

- Diplomacy and Peace: While conflict certainly existed, trade often served as a powerful incentive for peace. The mutual benefit derived from exchange created economic interdependence, making warfare costly and disruptive. Neutral zones, like the Pipestone Quarry, exemplified the prioritization of shared resources over tribal conflict.

- Prestige and Status: Possession of rare, exotic trade goods, especially those from distant lands like marine shells or copper, conferred prestige and status upon individuals and entire communities. Such items often found their way into burial sites, signifying their importance in life and beyond.

The Enduring Legacy

The arrival of Europeans, with their horses, guns, and diseases, dramatically altered these ancient networks. The introduction of the horse, in particular, revolutionized mobility and warfare, changing the dynamics of hunting and trade. European manufactured goods quickly integrated into, and eventually dominated, the existing trade systems, often shifting the focus from indigenous resources to furs and pelts sought by colonial powers.

Yet, the foundations laid by millennia of pre-contact trade endured. The routes, the inter-tribal relationships, and the deep-seated understanding of exchange as a vital aspect of life continued, adapting to new circumstances. The "invisible highways" of the Great Plains demonstrate a profound truth: Indigenous societies were dynamic, interconnected, and highly adaptive, engaging in complex economic and social systems that were vital to their survival and flourishing.

Unraveling these pre-contact trade networks offers a richer, more accurate understanding of the Great Plains’ Indigenous past. It reveals a landscape not of isolated groups, but of vibrant, interconnected nations, whose ingenuity, diplomacy, and spirit of enterprise forged a remarkable web of relationships across a vast and diverse continent. Their legacy continues to whisper through the archaeological record, a testament to the enduring power of human connection and exchange.