The Silent Libraries: Pre-Columbian Bark Paper Books and the Echoes of Hieroglyphic Writing

In the verdant heart of Mesoamerica, centuries before European ships ever grazed its shores, vibrant civilizations flourished, cultivating not only sophisticated agricultural systems and monumental architecture but also an advanced intellectual tradition. At the core of this intellectual prowess lay a remarkable innovation: bark paper books, meticulously crafted and adorned with intricate hieroglyphic writing. These codices, veritable libraries of ancient knowledge, offered a window into the cosmology, history, science, and daily lives of peoples like the Maya, Aztec, and Mixtec. Yet, their story is one of both profound creation and tragic destruction, a testament to human ingenuity and the devastating impact of conquest.

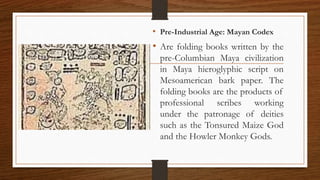

The very foundation of these ancient texts was a testament to indigenous resourcefulness: amate in Nahuatl, huun in Yucatec Maya – bark paper. Unlike the papyrus of Egypt or the parchment of Europe, Mesoamerican paper was typically made from the inner bark of various fig trees, most notably Ficus cotinifolia and Ficus insipida. The process was laborious, demanding skill and patience. Bark strips were harvested, soaked in water, then pounded with stone mallets on a flat surface until the fibers matted together into a cohesive sheet. This nascent paper was then coated with a thin layer of white gesso or stucco, providing a smooth, bright canvas for the scribes and artists. The finished sheets were often joined together and folded in an accordion-like, screen-fold format, creating a long, continuous strip that could be read page by page or unfolded to reveal an entire narrative. The ends were sometimes attached to wooden or leather covers, protecting the precious contents within.

These codices were far more than mere records; they were living embodiments of knowledge, sacred objects imbued with power and meaning. They chronicled dynastic histories, astronomical observations, calendrical calculations, divinatory rituals, and complex mythologies. The scribes, often members of the elite or specially trained priests, were revered figures. Their craft required not only artistic talent but also a profound understanding of the complex hieroglyphic systems that formed the backbone of these texts.

Among the various Mesoamerican writing systems, that of the Classic Maya stands as arguably the most sophisticated and extensively documented. Maya hieroglyphic writing was a logo-syllabic system, meaning it combined logograms (signs representing whole words or concepts) with syllabic signs (representing sounds). This allowed for a remarkable flexibility in expression, capable of recording nuances of language, poetry, and intricate historical detail. A single glyph block might contain multiple signs, read in a specific order, often top-to-bottom, left-to-right.

"The Maya scribes were not just writers; they were artists, astronomers, historians, and theologians," notes Dr. Michael D. Coe, a pioneering figure in Maya studies. "Their codices represent a synthesis of art and science, a total vision of the cosmos."

The content of these codices was incredibly diverse. Astronomical almanacs, such as those found in the Dresden Codex, meticulously tracked the movements of Venus and other celestial bodies, predicting eclipses and guiding agricultural cycles. Divinatory manuals, like parts of the Madrid Codex, provided priests with guidelines for rituals, prophecies, and interpreting omens. Historical accounts, often found on stelae and palace walls but undoubtedly also in books, traced the genealogies and conquests of kings, solidifying their legitimacy and power. The Maya calendrical system, with its intricate Long Count, Tzolkin (260-day sacred calendar), and Haab’ (365-day civil calendar), was an omnipresent feature, linking human events to cosmic cycles.

Other Mesoamerican civilizations also produced their own remarkable bark paper books. The Mixtec codices, like the Codex Zouche-Nuttall or the Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus, are renowned for their vibrant pictorial narratives, which primarily recount dynastic histories, genealogies, and heroic sagas of rulers like Eight Deer Jaguar Claw. While their writing system was more logographic and less phonetic than the Maya, it was equally effective in conveying complex information through a rich visual language. The Aztec also produced codices, though fewer survived, focusing on tribute lists, historical narratives, and religious almanacs, often using a combination of pictograms, ideograms, and phonetic elements.

Then came 1519. The arrival of the Spanish conquistadors marked an irreversible turning point. What the Europeans encountered was a world utterly alien to their own, a sophisticated civilization they struggled to comprehend through the lens of their own rigid beliefs. The intricate hieroglyphs, the complex calendrical systems, and the polytheistic religions were immediately condemned as idolatrous, works of the devil.

The most infamous act of cultural destruction occurred on July 12, 1562, in Maní, Yucatán. Friar Diego de Landa, a Franciscan missionary, orchestrated an Auto de Fe (Act of Faith), where he ordered the mass burning of Maya codices. His own chilling account stands as a testament to the magnitude of the loss: "We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which there was not superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree, and caused them much affliction."

De Landa, ironically, later became a key figure in preserving some aspects of Maya culture, creating an "alphabet" of Maya glyphs (though flawed) and detailing their customs. But the damage was done. Thousands upon thousands of these invaluable repositories of knowledge, accumulated over centuries, went up in smoke, representing an incalculable loss for humanity.

Today, only a handful of Pre-Columbian codices survive, scattered in European libraries, poignant remnants of a vast literary tradition. For the Maya, a mere four are universally accepted as authentic: the Dresden Codex, the Madrid Codex, the Paris Codex, and the Grolier Codex (whose authenticity was debated for decades but is now largely accepted). From the Mixtec and Aztec traditions, a few more, like the Borgia Group codices (Borgia, Laud, Cospi, Fejérváry-Mayer, and Vaticanus B), offer tantalizing glimpses into their respective worlds.

The survival of these few books is a miracle, often attributed to their being sent back to Europe as curiosities or war spoils, escaping the systematic destruction that befell their brethren. Yet, their existence became a source of enduring mystery for centuries. The intricate glyphs remained unreadable, their silent voices locked away, a challenge to scholars and adventurers alike.

The journey to decipherment was long and arduous. Early attempts were often misguided, hampered by the assumption that Maya glyphs were purely ideographic or symbolic, akin to Egyptian hieroglyphs before the Rosetta Stone. The breakthrough came in the mid-20th century, largely through the work of Russian epigrapher Yuri Knorozov, who, despite working in isolation during the Cold War, recognized the phonetic (syllabic) component of Maya writing. His insights, initially met with skepticism in the West, were eventually confirmed and expanded upon by a generation of scholars including Michael Coe, Linda Schele, Floyd Lounsbury, and David Stuart.

Through decades of dedicated research, cross-referencing glyphs with images, calendrical data, and comparative linguistics with modern Maya languages, the code was cracked. Today, over 85% of Maya hieroglyphic texts can be read, unlocking a treasure trove of information that has revolutionized our understanding of these ancient civilizations. We now know the names of kings, the dates of their births and deaths, their alliances and conquests, their religious beliefs, and their profound scientific understanding.

The decipherment has revealed a world far more complex and dynamic than previously imagined. It has shown that the Maya were not simply peaceful astronomers, but also fierce warriors, powerful rulers, and sophisticated political actors. Their texts speak of elaborate rituals, human sacrifice, divine kingship, and a deep connection to the natural world and the cosmos.

Even today, new discoveries continue to shed light on this lost world. The murals of San Bartolo, Guatemala, uncovered in the early 2000s, feature some of the earliest known Maya writing and elaborate pictorial narratives, pushing back the timeline of Maya literacy. Ongoing archaeological work and epigraphic studies continue to refine our understanding, revealing nuances previously unseen.

The bark paper books and their hieroglyphic writing stand as a poignant reminder of humanity’s diverse intellectual heritage. They are a testament to the ingenuity of Pre-Columbian peoples, their capacity for abstract thought, scientific observation, and artistic expression. The story of their creation and near-total annihilation serves as a powerful cautionary tale about the fragility of cultural heritage in the face of intolerance and conquest. Yet, in the surviving codices and the tireless work of decipherment, the silent libraries of Mesoamerica have found their voices once more, speaking across centuries, inviting us to listen and learn from the echoes of a vibrant past.