The Paramount Chief and the Confederacy: Unraveling Powhatan Tribal Leadership and Authority

The arrival of English colonists at Jamestown in 1607 thrust the indigenous peoples of the Chesapeake Bay region onto the world stage, yet often through a lens clouded by European biases and misunderstandings. Among these formidable Native American nations, the Powhatan Confederacy, under the astute leadership of its paramount chief, Wahunsenacawh – known to the English simply as Chief Powhatan – stood as a testament to sophisticated political organization and strategic authority. Far from a collection of disparate tribes, the Powhatan Confederacy was a meticulously structured political entity, designed for governance, defense, and the maintenance of a complex social order. Understanding its leadership structure and the sources of its authority is crucial to appreciating the resilience and ingenuity of the Powhatan people in the face of existential threats.

At the apex of this elaborate system was Wahunsenacawh, a figure whose name echoed power and wisdom throughout the Tsenacommacah, his vast domain stretching across much of present-day eastern Virginia. He was not merely a tribal elder but a mamanatowick, a "great king" or "paramount chief," who had skillfully forged an empire from what were once independent Algonquian-speaking tribes. His authority was multifaceted, drawing from military prowess, spiritual sanction, economic control, and a deeply embedded social hierarchy.

Wahunsenacawh’s rise to power began not with inherited dominion over all of Tsenacommacah, but through a calculated process of conquest, diplomacy, and strategic alliances. English chroniclers like John Smith, despite their inherent biases, described him as a formidable and intelligent leader. Smith, in his Generall Historie, recounted Powhatan’s control over "thirty-odd" tribes, each with its own local chief, or werowance. This expansion, which occurred over several decades before the English arrival, was critical. It transformed a landscape of fragmented communities into a unified political entity capable of mobilizing significant resources and manpower.

The structure of Tsenacommacah resembled a paramount chiefdom, a hierarchical system where a central authority governs a network of subordinate communities. Wahunsenacawh ruled directly over six of the core tribes – the Powhatan, Arrohateck, Appamattuck, Pamunkey, Mattaponi, and Chiskiack – largely located around the falls of the James River. These were considered his "home" territories, where his personal influence was strongest. The remaining tribes were incorporated through conquest or diplomatic coercion, becoming tributaries to the paramount chief. They retained a degree of internal autonomy but were bound by an oath of fealty, required to pay regular tribute, and provide military assistance when called upon.

The local chiefs, or werowances, were the linchpins of this system. Each werowance was responsible for the governance of their specific town or tribe, managing daily affairs, administering justice, and ensuring the smooth functioning of their community. Their authority, however, was derived from and subservient to Wahunsenacawh. He had the power to appoint, confirm, or even depose werowances, particularly in the conquered territories, ensuring loyalty and preventing dissent. "He took great pains to consolidate his power," notes historian Helen Rountree, "and made sure that the werowances under him understood their place in the hierarchy." This careful management of local leadership was essential for maintaining the cohesion of the vast confederacy.

The sources of Wahunsenacawh’s authority were deeply interwoven with Powhatan worldview and practical necessity.

1. Military Power and Protection: A primary source of his authority was his proven ability to wage war and offer protection. The consolidation of Tsenacommacah was largely achieved through military campaigns, and his warriors were renowned for their skill and discipline. Tribes joined the confederacy, often willingly, for the security it offered against common enemies and for access to the paramount chief’s formidable military strength. This was particularly evident in the face of aggressive neighboring tribes, and later, the encroaching English.

2. Spiritual and Religious Authority: Wahunsenacawh was not just a political and military leader; he also held significant spiritual authority. The Powhatan believed in a complex pantheon of gods and spirits, overseen by a powerful creator deity. The mamanatowick was seen as having a special connection to these spiritual forces, a conduit between the earthly and divine realms. Priests, known as quioccosan, played a crucial role in ceremonies and divination, but their power was often exercised in concert with, or under the ultimate authority of, the paramount chief. This spiritual sanction imbued Wahunsenacawh’s decisions with a sacred legitimacy, making defiance not just a political act, but a spiritual transgression.

3. Economic Control and Redistribution: Wahunsenacawh exercised significant control over the confederacy’s economy. The tribute system was central to this. Subordinate tribes provided him with a portion of their harvest, furs, copper, and other valuable goods. This wealth was not merely for personal enrichment; it was a powerful tool for maintaining authority. Wahunsenacawh would redistribute these goods, sometimes to reward loyal werowances, sometimes to support communities in need, and often to reinforce his own status. Copper, in particular, was a highly prized commodity, used for adornment and as a symbol of status. Control over its distribution further solidified his position as the ultimate arbiter of wealth and power. "He kept a treasury," John Smith noted, "of his own and other men’s skins, copper, pearl, and all manner of other commodities." This ability to accumulate and distribute wealth underscored his central role in the economic life of Tsenacommacah.

4. Matrilineal Succession: Unlike European systems, Powhatan leadership succession was matrilineal. Authority passed not from father to son, but often from a chief to his brother, then to his sister’s sons. This system, common among many Eastern Woodlands peoples, was designed to ensure continuity and prevent internal power struggles. It also highlighted the crucial role of women in Powhatan society, as lineage was traced through the female line. Wahunsenacawh himself was succeeded by his brothers, Opitchapam and Opechancanough, rather than his sons. This system provided a degree of stability that could be lacking in patrilineal monarchies, where disputes over primogeniture were common.

Decision-making within the confederacy was a delicate balance between the paramount chief’s ultimate authority and a form of consensual governance. While Wahunsenacawh had the final say, important decisions, especially those concerning war or peace, were often discussed in councils involving the werowances and other prominent men. This consultative process allowed for the airing of grievances, the gathering of intelligence, and the building of consensus, which in turn strengthened the legitimacy of the ultimate decision. It ensured that directives were not simply imposed but were understood and, ideally, supported by the broader leadership.

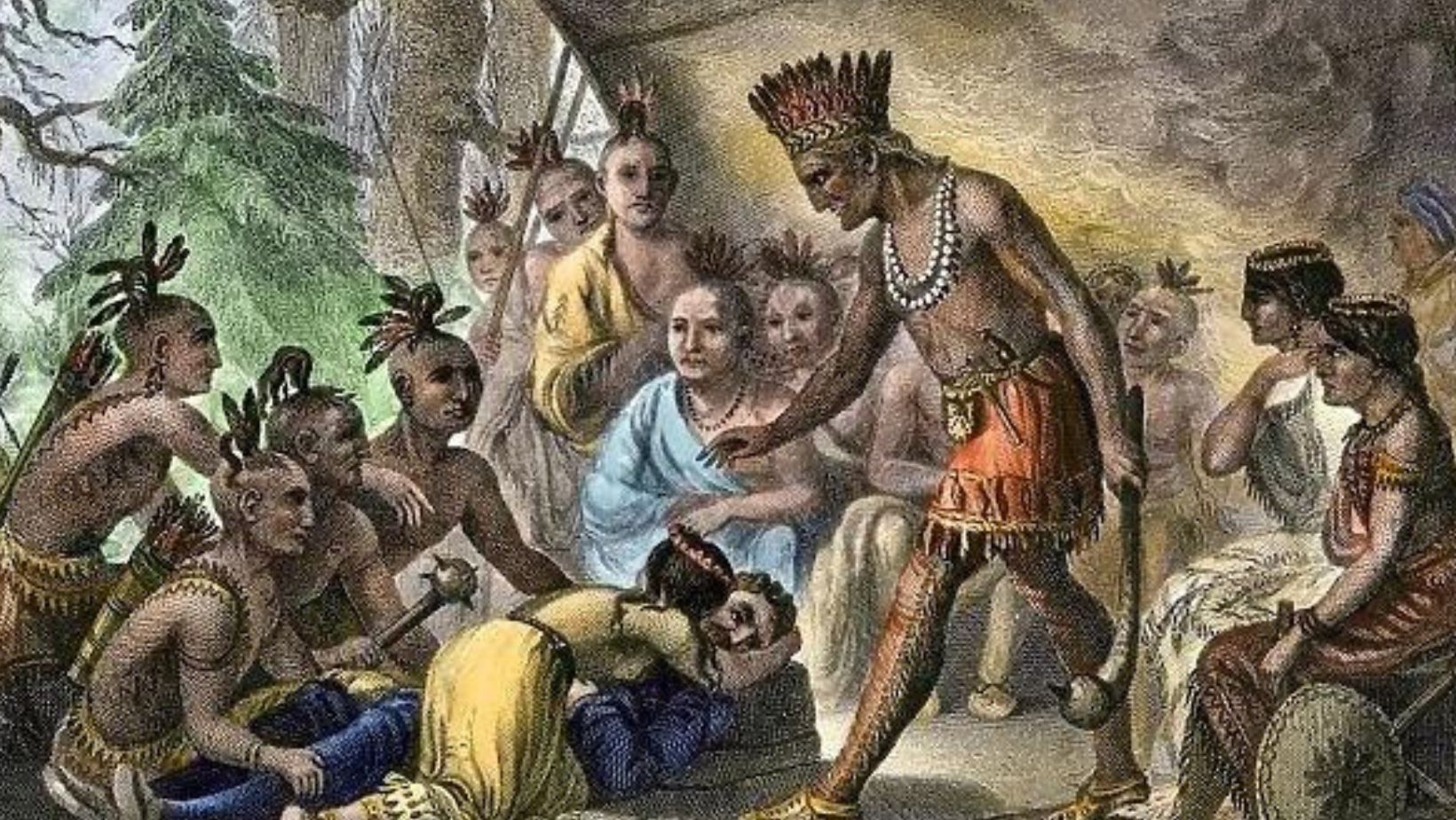

The arrival of the English presented the Powhatan leadership with its greatest challenge. Wahunsenacawh initially attempted to incorporate the newcomers into his existing system, seeing them as another tributary group. He offered trade and protection, but also exerted his authority through intimidation and calculated displays of power, such as the famous (and perhaps staged) "rescue" of John Smith by Pocahontas. His diplomatic exchanges with Smith reveal a leader keenly aware of the strategic implications of the English presence.

In one notably powerful, though likely paraphrased, exchange with John Smith, Powhatan articulated his desire for peace and the wisdom of avoiding conflict: "Why should you take by force that which you may have by love? Why should you destroy us who have provided you with food? What can you get by war? We are unarmed, and willing to give you what you ask, if you come in a friendly manner." This quote, whether exact or embellished, captures the strategic mind of a leader who understood the devastating costs of war and sought to preserve his people and their way of life.

However, the English proved unwilling to submit to Powhatan authority, driven by their own imperial ambitions and a fundamental misunderstanding of indigenous sovereignty. The conflict that ensued strained the confederacy, though its robust leadership structure allowed it to mount a significant and prolonged resistance. Even after Wahunsenacawh’s death, his successors, particularly Opechancanough, continued to leverage the established hierarchy to launch major offensives against the English colonists in 1622 and 1644. These efforts, while ultimately unsuccessful in expelling the English, demonstrated the enduring strength and coherence of the Powhatan leadership system.

In conclusion, the Powhatan Tribal Leadership Structure and Authority, as embodied by Wahunsenacawh and his confederacy, was a highly sophisticated and effective system. It was built on a foundation of military might, spiritual legitimacy, economic control, and a hierarchical yet adaptable political framework. The paramount chief, supported by a network of subordinate werowances, commanded a vast domain, maintained order, and provided for his people. The matrilineal succession ensured stability, while a blend of ultimate authority and consultative decision-making fostered cohesion. The Powhatan Confederacy stands as a powerful testament to indigenous political ingenuity, a complex and resilient entity that, despite facing overwhelming external pressures, skillfully navigated the tumultuous landscape of early colonial America, leaving an indelible mark on the history of the continent. Understanding its intricacies allows for a more accurate and respectful appreciation of the rich and complex societies that thrived in North America long before the arrival of Europeans.