Echoes of Treaties, Trails of Resilience: The Enduring Saga of the Potawatomi Nation

The story of the Potawatomi people, often referred to as "Keepers of the Fire," is a powerful narrative woven with threads of deep cultural heritage, strategic alliances, profound betrayals, and ultimately, an unyielding resilience. From their ancient homelands around the Great Lakes to their forced dispersion across the American Midwest, the Potawatomi’s journey encapsulates the broader, often tragic, history of Indigenous nations in North America, particularly their experiences with treaties and the relentless march of U.S. expansion.

The Keepers of the Fire: Ancient Roots and European Contact

For centuries before European arrival, the Potawatomi, an Algonquian-speaking people, were an integral part of the Anishinaabeg Confederacy, alongside the Ojibwe (Chippewa) and Odawa (Ottawa). Their ancestral lands spanned a vast and fertile crescent around Lake Michigan, encompassing parts of modern-day Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. They were skilled hunters, fishers, and farmers, living in harmony with the rich natural resources of the Great Lakes region. Their name, Bodéwadmi (Potawatomi), meaning "Keepers of the Fire" or "People of the Place of the Fire," reflects their traditional role as the central fire of the Confederacy, symbolizing their spiritual and diplomatic importance.

The arrival of French traders and missionaries in the 17th century marked the beginning of profound changes. The Potawatomi quickly adapted, integrating European goods like firearms and metal tools into their lives and becoming key partners in the lucrative fur trade. Their strategic location and diplomatic acumen made them powerful allies, first for the French against the British, and later for various factions during the tumultuous periods of colonial conflict. They played significant roles in pivotal events like Pontiac’s War in the 1760s, a widespread Indigenous resistance movement against British encroachment.

However, the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War and the subsequent birth of the United States introduced a new, far more aggressive, and ultimately devastating force: the relentless westward expansion of American settlers.

The Dawn of the Treaty Era: Promises and Pressures

The post-Revolutionary War period saw the U.S. government adopting a policy of acquiring Indigenous lands primarily through treaties. While ostensibly agreements between sovereign nations, these treaties were often negotiated under duress, with vastly unequal bargaining power, and frequently with little regard for Indigenous communal land ownership concepts or traditional governance structures.

The first major treaty involving the Potawatomi was the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. Signed after the defeat of a pan-tribal confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, this treaty established a "treaty line" in Ohio and Indiana, ceding large swaths of Indigenous territory to the U.S. and setting a precedent for future land cessions. For the Potawatomi, it was the first crack in the foundation of their ancestral domain.

The early 19th century brought increasing pressure. The War of 1812 saw many Potawatomi warriors fighting alongside Tecumseh’s Confederacy and the British, hoping to stem the tide of American expansion. Their defeat, however, only strengthened the U.S. resolve to "pacify" and dispossess Indigenous nations.

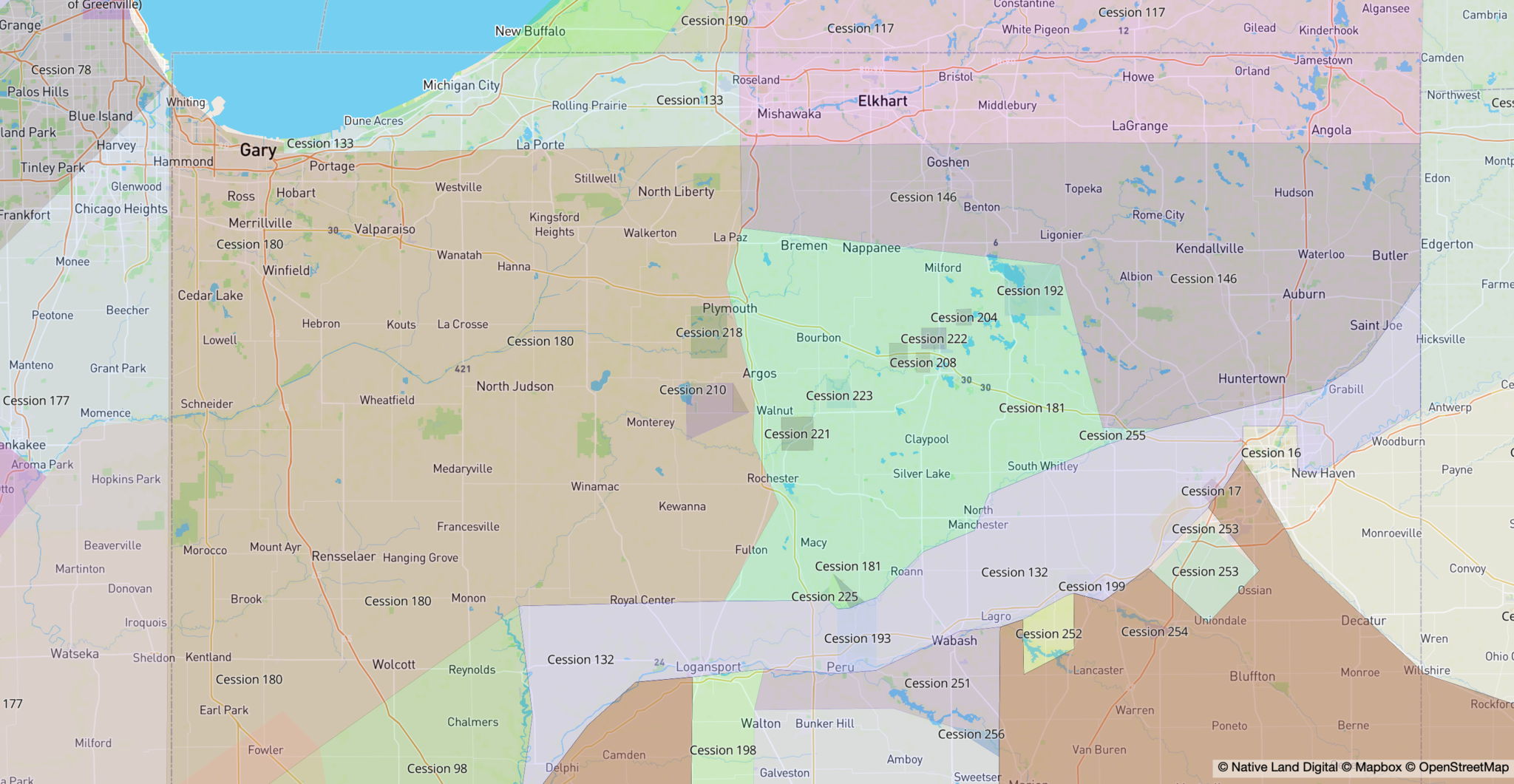

The Treaty Onslaught: A Cascade of Cessions

Between 1795 and 1867, the Potawatomi signed over 40 treaties with the United States. Each treaty chipped away at their territory, like stones eroding a mountain. These agreements were characterized by:

- Unequal Power Dynamics: U.S. commissioners often used threats, economic leverage, and alcohol to manipulate tribal leaders. As one observer noted of the era, "whiskey treaties" were not uncommon, where leaders were plied with alcohol until they signed away lands.

- Language Barriers and Misunderstandings: Treaties were written in English, often translated imperfectly, and sometimes deliberately misrepresented. The concept of "selling" land was alien to many Potawatomi, who viewed land as something to be shared and stewarded, not owned outright.

- Appointed vs. Traditional Leaders: U.S. officials often bypassed traditional, respected leaders, instead recognizing or even appointing "chiefs" who were more amenable to their demands, further undermining tribal sovereignty.

- The "Civilization" Policy: Treaties often included provisions for annuities (payments), tools, and "education" aimed at assimilating the Potawatomi into American farming society, a thinly veiled attempt to dismantle their cultural identity.

Major treaties included:

- Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809): Ceded significant lands in Indiana and Illinois, sparking outrage among Indigenous leaders like Tecumseh.

- Treaties of Chicago (1821, 1833): These were particularly devastating. The 1821 Treaty of Chicago saw the Potawatomi cede a vast tract of land along the southern and western shores of Lake Michigan. Just over a decade later, the 1833 Treaty of Chicago marked the final, major cession of Potawatomi lands in Illinois and Wisconsin, effectively removing them from their cherished homeland around Chicago, which was rapidly developing into a major American city. This treaty, often referred to as the "Last Treaty," promised removal to lands west of the Mississippi within five years.

The cumulative effect of these treaties was the dramatic shrinkage of Potawatomi territory from millions of acres to scattered, small reserves, and ultimately, to no land at all in their ancestral homelands.

The Trail of Death: Forced Removal

The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, formalized the U.S. policy of forcibly relocating Indigenous nations from their eastern lands to territories west of the Mississippi River. For the Potawatomi, this culminated in the brutal 1838 forced removal, known as the "Potawatomi Trail of Death."

In September 1838, approximately 859 Potawatomi, primarily from northern Indiana, were forcibly marched from Twin Lakes, Indiana, to lands in present-day eastern Kansas. Under the command of General John Tipton and accompanied by armed militia, the journey was a horrific ordeal. Lacking adequate food, water, and medical supplies, exposed to disease and exhaustion, over 40 Potawatomi died during the 660-mile trek, primarily women, children, and the elderly. The sick were often left behind or buried in unmarked graves along the trail. One survivor, recorded later, recalled, "The tears of the women and children were mingled with the dust of the road, and their lamentations filled the air." This tragic event stands as a stark testament to the inhumanity of the removal policy.

Scattered Nations, Resilient Spirits

The forced removals scattered the Potawatomi people. While many were removed to Kansas, where the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation resides today, others were moved to Indian Territory (Oklahoma), forming the foundation of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. Some groups, having resisted removal or secured special provisions in treaties, managed to remain in their traditional homelands, giving rise to the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians in Michigan and Indiana, and the Forest County Potawatomi Community in Wisconsin. Other smaller bands like the Hannahville Indian Community, the Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Potawatomi, and the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi also maintain their presence in Michigan.

Upon arrival in their new, unfamiliar territories, the Potawatomi faced immense challenges. They had to adapt to new climates, new agricultural methods, and the constant threat of further encroachment. The U.S. government continued its assimilation policies, culminating in the Dawes Act of 1887, which broke up communal tribal lands into individual allotments, further reducing Indigenous land bases and attempting to dissolve tribal identity.

The Path Forward: Sovereignty, Revitalization, and Self-Determination

Despite centuries of dispossession, disease, and attempts at cultural eradication, the Potawatomi people have endured. The mid-20th century saw a shift in U.S. policy towards self-determination, which allowed tribes to rebuild their governments, economies, and cultural practices.

Today, the various Potawatomi nations are vibrant, sovereign entities. They have successfully leveraged gaming enterprises and diversified businesses to create economic stability for their communities. This economic strength has, in turn, fueled a powerful resurgence in cultural revitalization:

- Language Programs: Efforts are underway to teach the Potawatomi language (Neshnabémwen) to younger generations, ensuring its survival.

- Cultural Preservation: Traditional ceremonies, storytelling, and artistic expressions are being revived and celebrated.

- Education: Tribes invest heavily in education, from early childhood to higher learning, empowering their members.

- Land Claims and Legal Battles: Many Potawatomi nations continue to pursue legal avenues to address historical injustices, including land claims and treaty rights.

The story of the Potawatomi is a profound lesson in resilience. From being the "Keepers of the Fire" in the vast Great Lakes region, through the crucible of treaties that stripped them of their lands, and the harrowing experience of forced removal, they have maintained their identity and their spirit. Their journey from ancient traditions to modern sovereignty stands as a testament to the enduring strength of a people who, against overwhelming odds, continue to protect their fire for future generations, ensuring their echoes resonate vibrantly in the fabric of North America.