The Unseen Fire: How Pontiac’s Rebellion Forged a Continent’s Future

In the annals of American history, certain pivotal moments are etched deep into the collective consciousness: the Boston Tea Party, the Declaration of Independence, the crossing of the Delaware. Yet, often overshadowed by the grand narrative of colonial rebellion, lies a conflict of profound and lasting consequence, a conflagration that ignited a mere decade before the shots at Lexington and Concord: Pontiac’s Rebellion. From 1763 to 1766, a confederacy of Native American nations, galvanized by spiritual revival and a shared sense of grievance, rose up against the victorious British Empire, inadvertently setting in motion a chain of events that would irrevocably alter the course of North American history and ultimately, sow the seeds of the American Revolution.

The stage for this monumental uprising was set by the Treaty of Paris in 1763, which formally concluded the French and Indian War (the North American theater of the Seven Years’ War). France, defeated, ceded its vast territorial claims in North America to Great Britain. While the British celebrated their newfound dominance, for the Indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes and Ohio River Valley, this victory was a harbinger of disaster. The "middle ground"—a complex diplomatic and economic ecosystem forged over generations between various Native nations and the French—evaporated overnight.

The French had cultivated alliances through trade, respect for Indigenous customs, and a more accommodating approach to land use. British policy, by contrast, was marked by arrogance and a stark disregard for Native sovereignty. General Sir Jeffery Amherst, the British commander-in-chief in North America, famously dismissed Indigenous gift-giving protocols as an expensive "Bribe" and cut off the supply of gunpowder, lead, and other crucial goods. He viewed Native Americans not as allies, but as conquered subjects, their lands ripe for settlement. This shift was catastrophic, threatening not only Indigenous economies but their very way of life and spiritual identity.

It was into this volatile environment that a new spiritual and political movement emerged. Neolin, a Delaware prophet, preached a message of nativist revival: reject European goods, alcohol, and customs, and return to traditional ways. He urged his followers to cast off the "white man’s burdens" and reclaim their ancestral lands, proclaiming that the Master of Life had commanded, "You must not allow the white man to keep even a single thread of the land that I have given to you." This spiritual awakening provided the ideological bedrock for a pan-Indian resistance.

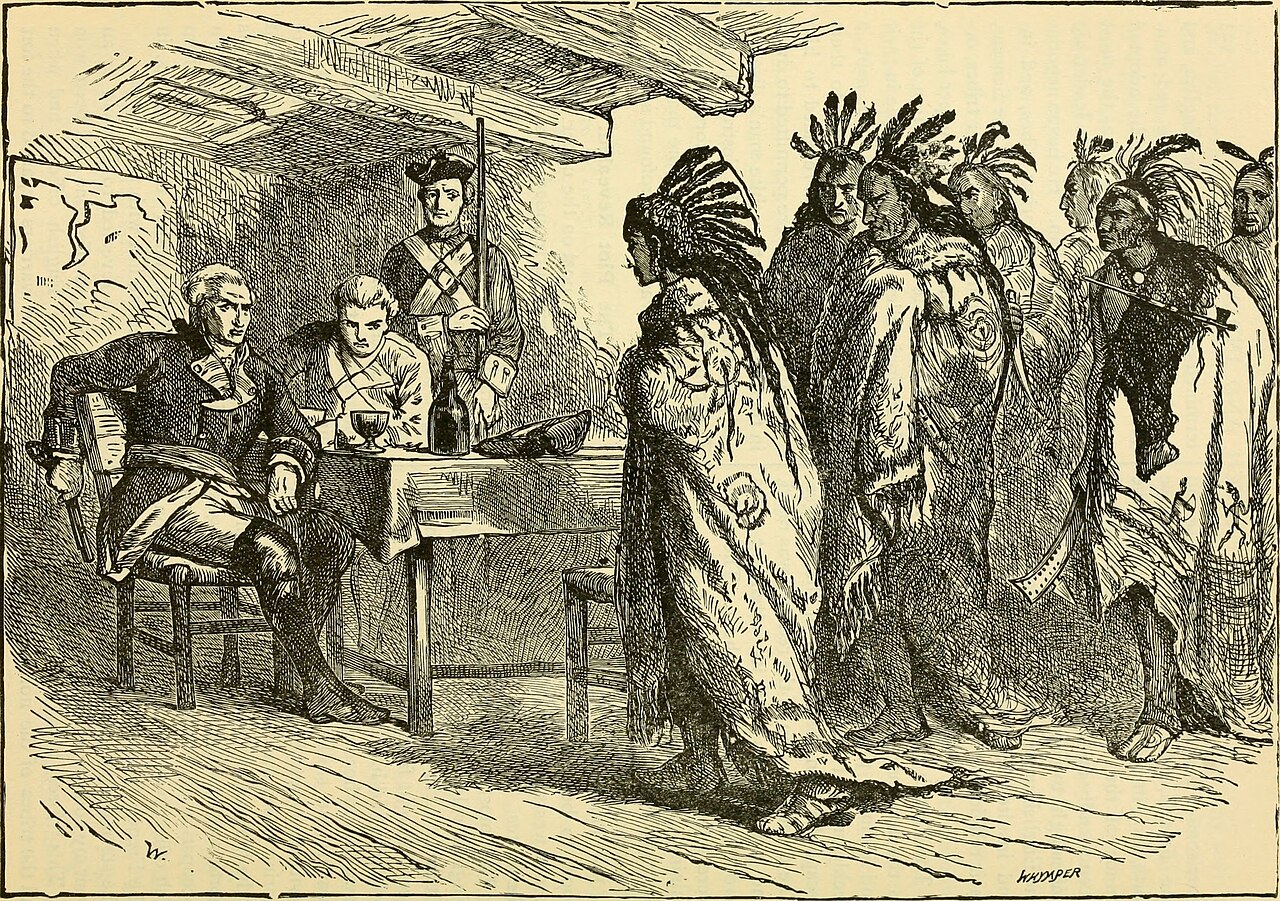

The charismatic Odawa chief Pontiac seized upon this fervor, transforming spiritual revival into military action. A brilliant orator and strategist, Pontiac articulated the existential threat posed by the British: "When I go to see the English commander and say to him that some of our brothers are dead, instead of giving me a blanket or a piece of meat to cover the dead, as my brother the French would do, he tells me: ‘When you are dead, I will send the dogs to eat your flesh!’" He envisioned a grand confederacy, a united front capable of expelling the British from Indigenous territories.

In the spring of 1763, Pontiac’s vision materialized. A meticulously coordinated series of attacks swept across the frontier, targeting British forts from Pennsylvania to Michigan. Nine of the eleven British forts west of the Appalachians were captured or destroyed, often by cunning deception rather than direct assault. Fort Detroit, where Pontiac personally led a siege that lasted for months, and Fort Pitt (modern-day Pittsburgh) became focal points of the conflict. The British garrisons, isolated and undersupplied, faced desperate odds.

The brutality of the conflict was not one-sided. British responses were equally merciless. In a chilling exchange that remains a dark stain on military history, General Amherst, exasperated by the resistance, infamously suggested to Colonel Henry Bouquet, "Could it not be contrived to Send the Small Pox among those disaffected Tribes of Indians?" Bouquet’s reply indicated he would try, leading to the controversial distribution of infected blankets from the Fort Pitt infirmary to Lenape (Delaware) envoys, an early, horrific instance of biological warfare. While the full extent of its impact is debated, the intent was clear: to decimate the Indigenous population.

The rebellion, though ultimately unable to dislodge the British entirely, achieved a significant strategic victory: it forced the British Crown to fundamentally re-evaluate its imperial policies. The immediate aftermath was costly for both sides. The British suffered thousands of casualties and immense financial losses, pushing an already debt-ridden empire further into the red. By 1764, British counter-offensives led by Bouquet and Colonel John Bradstreet began to regain control, but the war of attrition had taken its toll. Treaties were eventually signed, and while Pontiac himself was later assassinated in 1769, the spirit of resistance he embodied had left an indelible mark.

The historical significance of Pontiac’s Rebellion radiates in several critical directions, fundamentally shaping the future of North America:

1. The Proclamation of 1763: A Defining Imperial Pivot:

The most direct and immediate consequence of Pontiac’s War was the Royal Proclamation of 1763. Issued by King George III, this decree drew an imaginary line along the Appalachian Mountains, reserving all lands west of it for Native American occupation and forbidding colonial settlement without Crown approval. The Proclamation was a desperate attempt by the British to prevent future costly conflicts, stabilize the frontier, and regulate westward expansion. It aimed to manage a vast new empire, but in doing so, it inadvertently created a deep chasm between imperial policy and colonial ambition.

2. Fueling Colonial Discontent and the Road to Revolution:

For American colonists, the Proclamation of 1763 was an infuriating act of imperial overreach. Many viewed it as an arbitrary restriction on their "God-given right" to expand westward, particularly after fighting and dying in a war they believed secured these lands for them. George Washington, a prominent land speculator, openly defied it, stating, "I can never look upon that Proclamation in any other light than as a temporary expedient to quiet the Minds of the Indians."

Furthermore, the need to maintain a standing army in North America to enforce the Proclamation Line and protect the frontier led to increased British military presence in the colonies. This presence, and the subsequent efforts to tax the colonists to pay for it (through acts like the Sugar Act, Stamp Act, and Quartering Act), ignited fierce resentment. The costs associated with Pontiac’s Rebellion directly contributed to the British government’s determination to extract revenue from its American colonies, thereby fanning the flames of revolutionary sentiment. The rebellion, therefore, inadvertently became a critical precursor to the American Revolution, sharpening the very grievances that would lead to armed conflict.

3. The Persistence of Indigenous Resistance and Pan-Indian Identity:

While Pontiac’s Rebellion did not achieve its ultimate goal of expelling the British, it demonstrated the formidable power of united Indigenous resistance. It laid the groundwork for future pan-Indian movements, inspiring leaders like Tecumseh decades later. The war showed that Native nations were not merely passive victims of colonial expansion but active agents determined to defend their sovereignty and cultural integrity. It forced the British, and later the Americans, to acknowledge Indigenous power and negotiate for land, albeit often through coercive means. The Proclamation Line, imperfect as it was, stands as a testament to the success of Indigenous resistance in forcing the Crown to recognize their land claims, even if temporarily.

4. Redefining the North American Landscape and Power Dynamics:

Pontiac’s Rebellion fundamentally altered the demographic and political landscape of North America. It solidified the shift from a contested frontier involving multiple European powers to one dominated by a single, albeit challenged, British authority. It forced the British to develop a more structured, if often heavy-handed, approach to colonial administration and Indigenous relations. The conflict also highlighted the fragility of European control over vast interior territories, demonstrating that conquest was not a foregone conclusion but an ongoing struggle.

In conclusion, Pontiac’s Rebellion, often relegated to a footnote in the grand narrative of American history, stands as a critical hinge point. It was a powerful assertion of Indigenous sovereignty against an encroaching empire, a struggle born of desperation and spiritual revival. Its immediate aftermath, particularly the Royal Proclamation of 1763, inadvertently ignited the very tensions that would lead to the American Revolution, as imperial control clashed with colonial aspirations for westward expansion. The "unseen fire" of Pontiac’s Rebellion, therefore, not only illuminated the enduring spirit of Native American resistance but also cast a long shadow over the nascent American colonies, pushing them inexorably towards a declaration of independence and the birth of a new nation. Its legacy reminds us that the complex tapestry of American history is woven from many threads, some vibrant and celebrated, others darker and often overlooked, but all essential to understanding the continent we inhabit today.