Echoes in Time: The Enduring Legacy of Plains Pictographic Historical Calendar Systems

In the vast, undulating landscapes of the North American Great Plains, where the wind whispers through tall grasses and the horizon stretches limitlessly, Indigenous peoples developed sophisticated systems to chronicle their histories long before the advent of European written script. Among the most profound and culturally rich of these are the Plains Pictographic Historical Calendar Systems, often known as "winter counts" or, in Lakota, waníyetu wówapi. These unique visual narratives transcend mere date-keeping, serving as vibrant, living archives of community memory, spiritual understanding, and historical truth.

For centuries, before the arrival of European chroniclers, the Indigenous nations of the Plains – including the Lakota, Dakota, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Mandan, Hidatsa, and many others – relied heavily on oral tradition to transmit knowledge, laws, and history across generations. However, the sheer volume of information, coupled with the need for communal verification and a tangible point of reference, led to the development of these pictorial records. Unlike Western linear calendars, these systems often didn’t aim for precise dates but rather a sequence of memorable, culturally significant events, anchoring collective memory in a shared visual language.

At the heart of the system is the "winter count," a continuous annual record of tribal history, usually from one winter to the next, covering periods that could span a century or more. Each year was represented by a single pictograph, carefully chosen by a designated keeper or a council of elders to symbolize the most significant event that occurred during that particular winter-to-winter cycle. This was not a simple act of drawing; it was a profound act of historical curation, requiring consensus, wisdom, and a deep understanding of the community’s shared experiences.

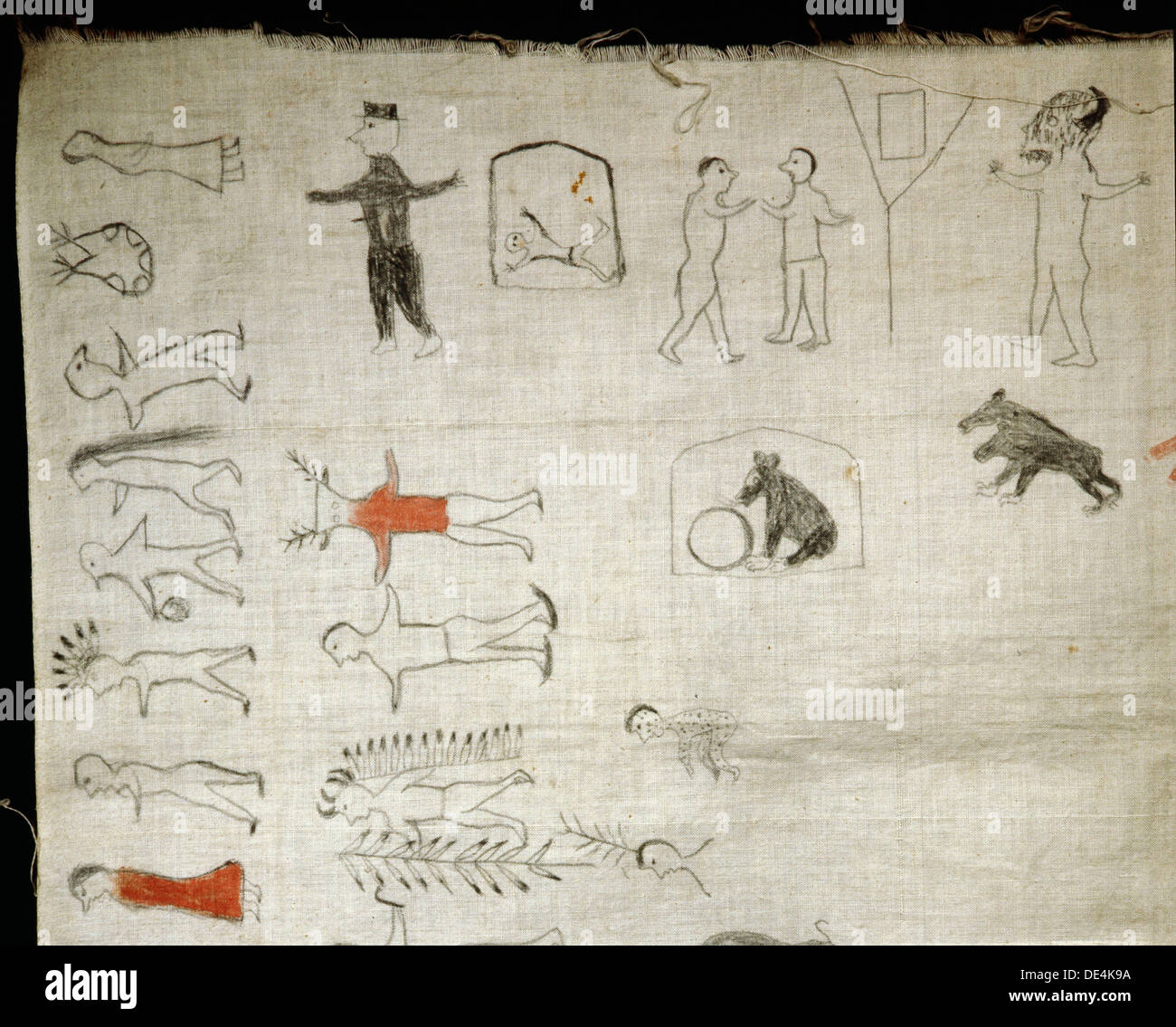

The materials used for these chronicles evolved over time. Early winter counts were typically painted or drawn on animal hides, most commonly buffalo or deer, prepared with meticulous care. The durable, pliable surface of a buffalo robe, often tanned and scraped smooth, provided an ideal canvas for the ochre, charcoal, and mineral pigments that formed the pictographs. As European trade goods became available, some keepers transitioned to using cloth or paper, which allowed for greater detail and annotation, especially in later periods. The arrangement of the pictographs varied; some followed a spiral pattern, starting at the center and moving outwards, while others progressed in a linear fashion, or even boustrophedon (like oxen plowing a field, alternating directions).

The events chronicled are as diverse as the lives of the people who kept them. They offer an unparalleled glimpse into the holistic worldview of Plains nations, encompassing natural phenomena, social developments, political milestones, and individual achievements. Natural events, often interpreted as omens or significant markers, feature prominently. For instance, many winter counts record the spectacular Leonid meteor shower of 1833, often depicted as "the year the stars fell." Epidemics, such as the devastating smallpox outbreak of 1837-38, which decimated many tribes, are also starkly represented, serving as grim reminders of collective trauma.

Beyond nature, the pictographs detail pivotal moments in tribal history: successful buffalo hunts that ensured survival, significant ceremonies like the Sun Dance, changes in leadership, peace treaties and conflicts with other tribes or encroaching settlers. Personal feats, such as a warrior’s brave deed or a chief’s wise decision, could also be deemed worthy of inclusion, reflecting the individual’s contribution to the collective good. "They are not just lists of events," explains Dr. Candace Greene, an ethnologist at the Smithsonian, "but rather a framework for oral history, a mnemonic device that allowed the keeper to recount the full story of each year."

One of the most widely studied examples is Lone Dog’s Winter Count, a Lakota record spanning from 1800 to 1870-71. Copied and studied by ethnographers like Garrick Mallery, Lone Dog’s count illustrates the breadth of events recorded. For the year 1800-01, it depicts "Thirty Dakotas were killed by the Crows" – a stark reminder of intertribal warfare. The year 1832-33 shows "The stars fell" (the meteor shower), a communal experience that left an indelible mark. Other entries detail horse-stealing raids, the first trading post, and treaty negotiations. Each pictograph, while simple in form, represents a complex narrative, requiring the spoken word of the keeper to unlock its full meaning.

Later, more detailed counts like that of Battiste Good (Lakota), created in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, show an evolution. Battiste Good, an Oglala Lakota, meticulously transcribed his count onto paper, often adding annotations in Lakota and English, reflecting the increasing interaction with and influence of American culture. His count begins not with a recent event but with a mythical past, tracing the origins of his people, demonstrating that these calendars were not solely about recent history but also about cultural identity and deep ancestral memory.

Beyond the Lakota, other nations maintained similar systems. The Plum’s Winter Count of the Mandan and Hidatsa peoples, for instance, provides a vital counterpoint, demonstrating the widespread adoption and adaptation of this calendrical tradition across different linguistic and cultural groups. Each tribe’s count, while sharing the core methodology, possessed its own unique iconography and emphasized events pertinent to its specific history and environment.

More than mere historical records, winter counts served as living archives, pedagogical tools, and even spiritual guides. They were "books of memory" that required an elder’s voice to bring them to life, transforming simple images into rich, detailed narratives. A keeper would sit with members of the community, especially the younger generation, and recount the stories associated with each pictograph, thereby transmitting not just facts, but cultural values, moral lessons, and a sense of shared heritage. They were instruments for social cohesion, reminding people of who they were, where they came from, and what they had endured together.

Interpreting these counts for outsiders, however, requires a deep understanding of the cultural context. The pictographs are highly stylized and symbolic, often intelligible only to those immersed in the cultural nuances of the specific nation. A simple circle might represent a camp circle, a treaty, or even a particular chief. The loss of native speakers and keepers, tragically brought about by forced assimilation policies, has made complete interpretation challenging for some older counts, highlighting the fragility of oral traditions without their living custodians.

The forced assimilation policies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries dealt a severe blow to the continuation of winter count traditions. Children were taken from their families and placed in boarding schools, where their languages and cultural practices were actively suppressed. The emphasis shifted from oral history and visual memory to written, Western-centric narratives. Many winter counts were confiscated, lost, or simply ceased to be maintained as their keepers passed on without apprentices.

Today, however, a powerful resurgence is underway. Indigenous communities are actively working to reclaim, revitalize, and understand their historical calendar systems. Scholars, often working in collaboration with tribal elders and cultural committees, are digitizing and studying existing counts, cross-referencing them with other historical records, and making them accessible to a wider audience. Institutions like the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian and the Native American Rights Fund are supporting these efforts, recognizing the immense value of these documents not only for Indigenous peoples but for a more complete understanding of American history.

This revitalization is not just an academic exercise; it’s a profound act of cultural resilience. Community workshops are being held where elders teach younger generations how to "read" the counts, to understand the symbolism, and to connect with the stories of their ancestors. Some communities are even creating new winter counts, bridging the past with the present, and ensuring that their contemporary histories are also recorded in this time-honored fashion. As one contemporary Lakota elder might say, "These are our textbooks. They tell us who we are and where we come from. They teach us resilience, wisdom, and how to walk in the world."

The Plains Pictographic Historical Calendar Systems stand as profound testaments to Indigenous ingenuity, historical consciousness, and the enduring power of cultural memory. They are far more than quaint relics of the past; they are dynamic, multifaceted historical documents that continue to speak across generations, offering invaluable insights into the lives, struggles, and triumphs of the Native nations of the Great Plains. In their intricate patterns and resonant symbols, they remind us that history is not solely written in words, but often painted in the echoes of time, waiting to be heard and understood anew.