Echoes on the Potomac: The Enduring Legacy of the Piscataway Conoy Tribe

By

The banks of the Potomac River, where modern Maryland hums with the rhythm of urban life and suburban sprawl, hold secrets much older than any colonial charter or federal building. These waters, these lands, were once – and in spirit, still are – the ancestral home of the Piscataway Conoy people, a confederacy of Algonquian-speaking tribes whose history is as deeply woven into the fabric of Maryland as the ancient oaks that once covered its hills. Their story is not merely one of the past but a vibrant testament to resilience, survival, and the enduring power of cultural identity in the face of centuries of challenge.

For over 13,000 years, the Piscataway and their allied tribes – including the Moyaone, Patuxent, Mattawoman, and others – thrived in the fertile crescent between the Potomac River and the western shores of the Chesapeake Bay. They were the "People of the Great River," their lives intrinsically linked to the bountiful waterways and rich forests. Their sophisticated society was built on a foundation of agriculture, primarily corn, beans, and squash, supplemented by expert hunting and fishing. Villages were strategically located along rivers, often fortified, and governed by a complex political structure led by a Tayac (paramount chief), who oversaw various werowances (sub-chiefs) of individual towns.

"Our ancestors were the original stewards of this land," explains Jesse Green, a prominent elder and former Chief of the Piscataway Conoy Tribe, his voice carrying the weight of generations. "They understood the balance of nature, the sacred connection between the people and the earth. Every tree, every stream, every animal had its place, and we were part of that intricate web." This deep spiritual and practical connection to the land informed every aspect of their lives, from their seasonal migrations to their ceremonial practices.

The Arrival of a New World: Clash and Compromise

The year 1634 marked an irreversible turning point. Lord Baltimore’s expedition, carrying English Catholic settlers, sailed into the Chesapeake Bay, seeking refuge and opportunity. Their arrival, chronicled by the Jesuit missionary Father Andrew White, describes a landscape already populated and politically organized. The English first landed at St. Clement’s Island (now Blackistone Island) and soon established St. Mary’s City, Maryland’s first permanent European settlement, near the Piscataway village of Moyaone.

Initial interactions were complex, a mix of curiosity, cautious diplomacy, and underlying tension. The paramount chief, Tayac Kittamaquund, then known as Wacoomes, played a pivotal role. Recognizing the technological superiority of the English and perhaps hoping to forge a strategic alliance against rival tribes like the Susquehannock, he entered into negotiations. In a move that would have profound implications, Kittamaquund, along with his wife and several advisors, converted to Catholicism in 1640, taking the Christian name Charles. This act, while seen by the English as a diplomatic triumph, simultaneously introduced an internal cultural fracture that would weaken the Piscataway’s traditional authority.

Despite early attempts at peaceful coexistence, the pressures of colonial expansion quickly mounted. The English demand for land was insatiable, driven by a growing population and the burgeoning tobacco economy. Treaties were often made under duress or misunderstood, with English concepts of land ownership – permanent, exclusive, and alienable – clashing fundamentally with Indigenous understandings of shared use and stewardship. "For us, the land was not something you ‘owned’ in the way the English did," says Green. "It was our mother, our provider. You didn’t sell your mother."

A Century of Displacement and Diminishment

The mid-to-late 17th century was a period of intense trauma and displacement for the Piscataway Conoy. Epidemics of European diseases – smallpox, measles, influenza – to which Indigenous peoples had no immunity, decimated their populations. Entire villages were wiped out, weakening their social structures and their ability to resist colonial encroachment.

As English settlements expanded, the Piscataway were pushed further and further inland, away from their ancestral lands along the Potomac. They found themselves caught between the advancing English and the aggressive incursions of northern tribes, particularly the Susquehannock and later the Iroquois Confederacy, who were also feeling the pressure of colonial expansion and seeking new hunting grounds for the lucrative fur trade.

A significant blow came with Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia in 1676. Though primarily a conflict between Virginia colonists and Native Americans, its ripple effects reached Maryland. The Piscataway, despite attempts to remain neutral or ally with the English, were caught in the crossfire. Colonial militias, often indistinguishable from renegade frontiersmen, attacked their villages. The fear and violence forced many Piscataway to seek refuge, eventually leading them to establish a fortified town at Zekiah Swamp in Charles County, and later, for some, to move north along the Susquehanna River into Pennsylvania, eventually merging with other displaced Algonquian groups like the Conoy and Nanticoke.

By the early 18th century, official colonial records began to declare the Piscataway and other Maryland tribes "extinct" or "removed." Their visible presence in their ancient homelands had diminished, and their names faded from public discourse. But this declaration was a colonial narrative, not a truth.

The "Hidden" Years: Survival in Plain Sight

Despite the official pronouncements, the Piscataway Conoy people never truly disappeared. They adopted a strategy of survival often referred to as "passing" or "going underground." Many remained in Maryland, living in small, often isolated communities, working on farms, intermarrying with free blacks and European indentured servants, and adapting to the changing landscape. They kept their traditions alive in secret, around kitchen tables, through oral histories passed from elders to children, and in spiritual practices maintained away from prying colonial eyes.

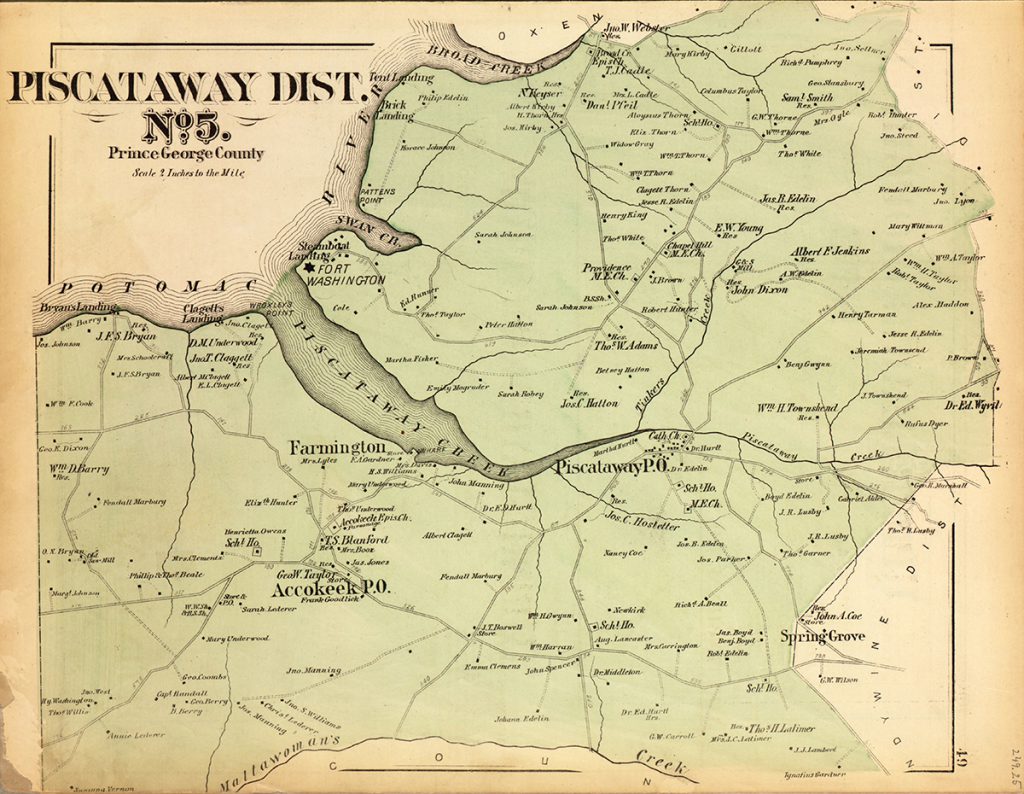

"Our families stayed together, always," affirms a tribal historian, who prefers to remain unnamed to respect the privacy of some community members. "We learned to blend in, to be quiet, but we never forgot who we were. The stories, the songs, the knowledge of the plants – it was all passed down. It had to be." This period of clandestine existence was critical for the preservation of their identity, ensuring that the thread of their heritage, though thin, never broke. Communities in areas like Charles County and Prince George’s County continued to be home to families who knew their Piscataway Conoy lineage, even if the outside world chose not to see it.

Re-Emergence and the Fight for Recognition

The late 20th century saw a resurgence of pride and a determined effort by the Piscataway Conoy to reclaim their rightful place in Maryland’s narrative. As historical research became more accessible and Indigenous communities across the nation began asserting their sovereignty, the Piscataway Conoy leaders embarked on the arduous journey towards official recognition.

This process, both at the state and federal levels, demands extensive genealogical and historical documentation, proving continuous existence as a distinct cultural and political entity. It’s a bureaucratic gauntlet designed to be challenging, often requiring tribes to "prove" what they already know to be true.

After decades of dedicated work, meticulous research, and passionate advocacy, the Piscataway Conoy Tribe achieved a monumental victory. On January 9, 2012, the State of Maryland officially recognized the Piscataway Conoy Tribe, along with the Piscataway Indian Nation and the Accohannock Indian Tribe. This recognition was not merely symbolic; it was an affirmation of their continuous existence, their inherent sovereignty, and their profound connection to the state.

"That day was an emotional one for so many of us," recalls Chief Green. "It wasn’t just a piece of paper; it was the state finally acknowledging what our ancestors knew all along – that we are still here, we never left, and our culture endures."

A Future Rooted in the Past

Today, the Piscataway Conoy Tribe is actively engaged in revitalizing its culture, language, and traditions. They host powwows, educational programs, and cultural events that share their history and heritage with the wider community. They advocate for environmental protection of their ancestral lands and waters, ensuring the health of the Chesapeake Bay watershed. They work to correct historical inaccuracies and ensure that the Indigenous perspective is included in Maryland’s educational curriculum.

Their journey from paramount chiefdoms to near obliteration, and then to a powerful re-emergence, offers invaluable lessons about the human spirit’s capacity for resilience. The echoes of their ancestors continue to resonate on the Potomac, a powerful reminder that history is not a static past but a living, breathing narrative that shapes our present and guides our future. The Piscataway Conoy Tribe stands as a testament to the enduring strength of a people who, against all odds, continue to protect their heritage, honor their ancestors, and forge a vibrant path forward. Their story is Maryland’s story, an essential and indelible part of its soul.