Pima Irrigation Systems: Ancient Desert Agricultural Engineering in the Southwest

In the harsh, sun-baked landscape of the Sonoran Desert, where rainfall is scarce and temperatures soar, the very idea of sustained agriculture seems an affront to nature. Yet, for millennia, a thriving civilization flourished along the Gila and Salt Rivers, not by defying the desert, but by masterfully understanding and harnessing its most precious resource: water. The Akimel O’odham, commonly known as the Pima people, are the living inheritors of a hydrological legacy that stretches back over two millennia, often linked directly to the enigmatic Hohokam culture. Their ancient irrigation systems represent one of the most sophisticated examples of pre-Columbian agricultural engineering in North America, a testament to human ingenuity, community cooperation, and a profound ecological wisdom.

The story of Pima irrigation is etched into the very earth of the Southwest. Before European contact, long before the advent of modern machinery, the ancestors of the Akimel O’odham transformed arid river valleys into verdant fields. Archaeological evidence suggests that extensive canal networks were first developed by the Hohokam people as early as 300 BCE, reaching their peak between 1150 and 1450 CE. When the Akimel O’odham arrived in the region, they revitalized and expanded upon these abandoned but still discernible channels, demonstrating a remarkable continuity of knowledge and adaptation. These systems were not mere ditches; they were engineered marvels, designed to capture, transport, and distribute water across vast agricultural landscapes.

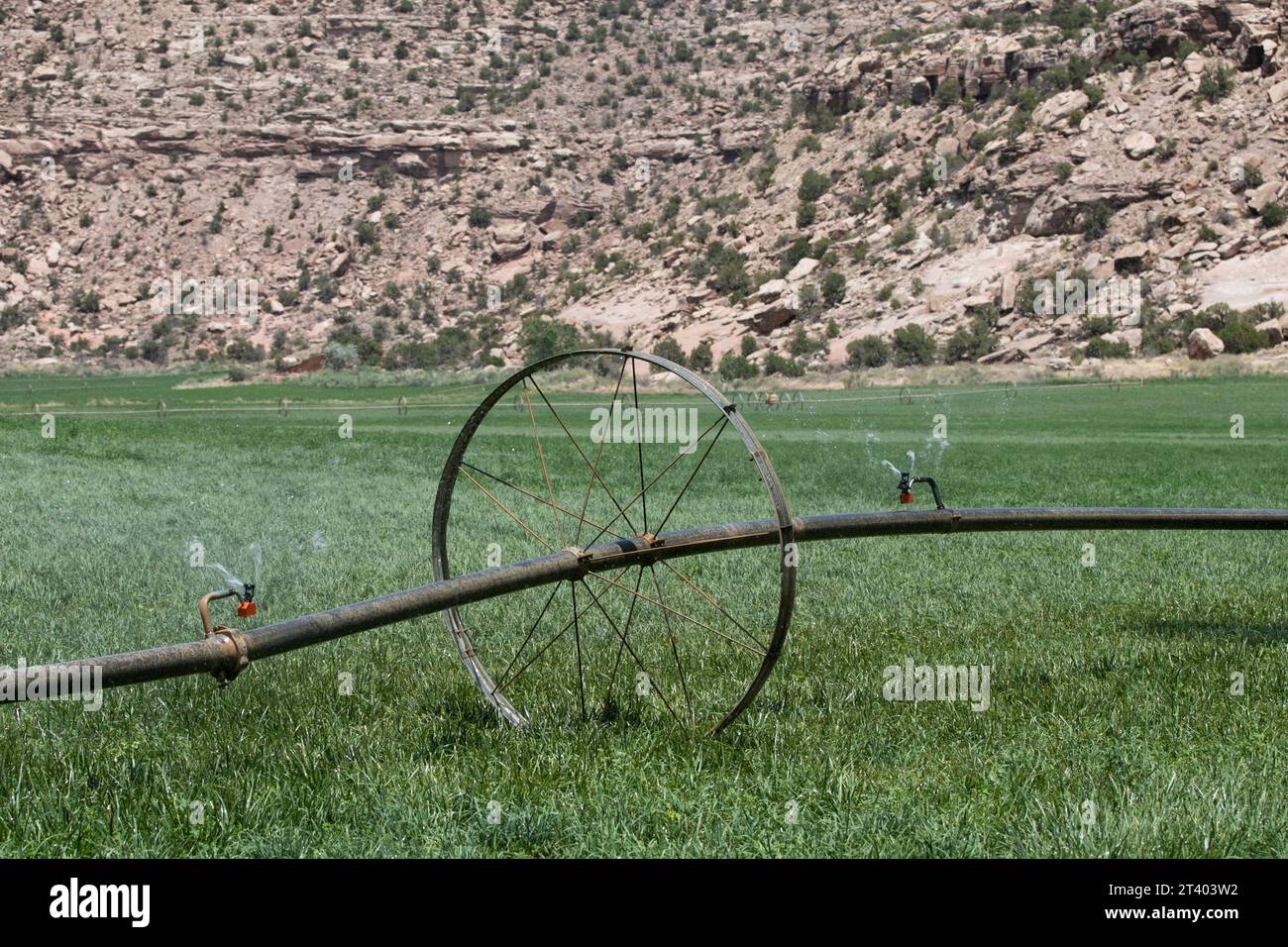

At the heart of this ancient engineering feat were the Gila and Salt Rivers. The Akimel O’odham, whose name translates to "River People," recognized these waterways as the lifeblood of their existence. Their canals, often hundreds of miles in cumulative length, were not built haphazardly. They employed sophisticated principles of hydraulics and surveying, guiding water from the main river channels to fields miles away. The gradient of these canals was incredibly precise—often less than a foot per mile—allowing water to flow gently enough to prevent erosion of the earthen channels, yet consistently enough to reach every cultivated plot. This delicate balance was achieved without metal tools, compasses, or modern levels, relying instead on keen observation, empirical knowledge, and an understanding of the subtle contours of the land.

Construction was a monumental community effort. Using nothing more than digging sticks, stone axes, and woven baskets to carry away excavated earth, generations of Akimel O’odham labored collectively to build and maintain these vital arteries. Main canals could be several feet deep and many feet wide, capable of carrying substantial volumes of water. From these main arteries, smaller lateral canals branched off, leading water directly to individual fields. Temporary brush and stone diversion dams, strategically placed in the river, were used to raise the water level sufficiently to feed into the main canal intakes. These dams, built and rebuilt seasonally after floods, showcased an intimate understanding of the river’s dynamics and the cyclical nature of its flow.

The crops cultivated by the Akimel O’odham were as resilient as their water management. The "Three Sisters"—corn, beans, and squash—formed the cornerstone of their diet, providing a balanced nutritional foundation. Corn, in particular, thrived under irrigation, with various drought-resistant strains adapted to the desert environment. Cotton was another crucial crop, not only for textiles and clothing but also as a valuable trade commodity. Gourds, sunflowers, and other native plants supplemented their agricultural bounty. Their farming practices were remarkably sustainable, integrating flood silting to replenish soil nutrients and rotating crops to maintain fertility without the use of artificial fertilizers. The entire system was a closed loop of human ingenuity and natural processes, harmoniously integrated.

Beyond the physical engineering, the Pima irrigation systems represented a profound social and political achievement. Managing such an extensive and vital resource required a highly organized society. Water allocation, especially during periods of drought, was governed by established customs and traditions, often overseen by "ditch bosses" or similar community leaders. These individuals possessed deep knowledge of the canal system, the river’s flow, and the needs of the community. Decisions regarding water distribution were crucial for survival and were typically made through consensus, emphasizing cooperation over individual gain. The entire community understood that their collective survival depended on the fair and efficient management of this shared resource. Water was not merely a commodity; it was a sacred element, inextricably linked to their spiritual beliefs, ceremonies, and identity as the "River People."

The enduring legacy of the Akimel O’odham’s ancient agricultural engineering is both inspiring and tragic. For centuries, their systems sustained a vibrant culture. However, with the arrival of American settlers in the late 19th century, the Pima’s traditional way of life was catastrophically disrupted. Upstream diversions of the Gila River by non-native farmers drastically reduced the water available to the Akimel O’odham, leading to the collapse of their agricultural economy and severe hardship. The once-thriving fields turned to dust, and a people who had never known hunger faced starvation. This injustice led to decades of legal battles for water rights, culminating in significant settlements like the Gila River Indian Community Water Settlement Act of 2004, which sought to restore a measure of justice and water security.

Today, the ancient Pima irrigation systems stand as a powerful reminder of indigenous ingenuity and a living lesson in sustainable water management. Their methods, developed through centuries of trial and error, offer valuable insights for modern arid-land agriculture and urban planning. The Akimel O’odham demonstrated that thriving in a desert is not about conquering nature, but about understanding its rhythms, respecting its limits, and working collaboratively with its forces. Their mastery of water engineering, achieved with minimal technology, stands as a testament to the power of observation, collective effort, and a deep, abiding connection to the land. As the Southwest grapples with increasing water scarcity due to climate change and population growth, the ancient desert agricultural engineering of the Pima people offers not just a historical curiosity, but a profound and urgently relevant model for the future. Their canals, though sometimes hidden beneath the modern landscape, continue to whisper tales of resilience, innovation, and a civilization that truly lived in harmony with its environment.