Penobscot River’s Enduring Legacy: The Art of Traditional Birchbark Canoe Building

The Penobscot River, a vast artery through the heart of Maine, has for millennia been the lifeblood of the Penobscot Nation. It was here, amidst the whispering pines and ancient hardwoods, that an extraordinary craft was perfected: the birchbark canoe. Far more than a simple vessel, these canoes represent an intricate tapestry of engineering, artistry, and a profound spiritual connection to the land and its resources, embodying construction methods passed down through countless generations. This is a journey into the meticulous, demanding, yet deeply rewarding process of building a Penobscot birchbark canoe.

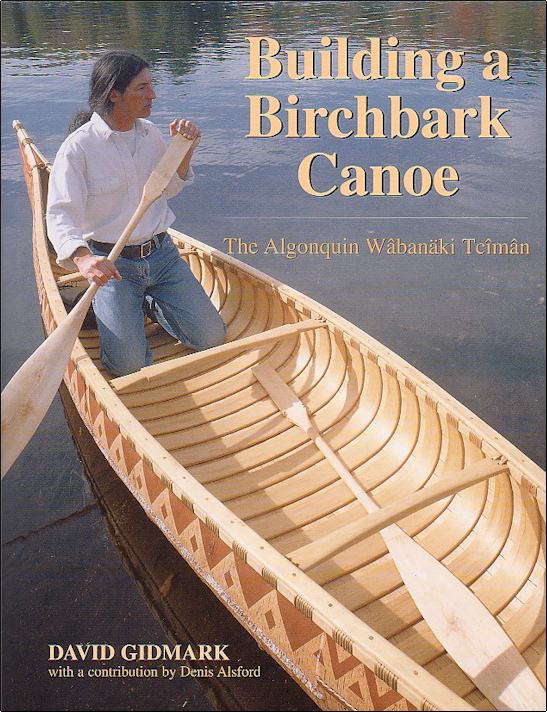

The Penobscot canoe is not merely a mode of transport; it is a living testament to indigenous ingenuity. Its design, refined over thousands of years, allowed for silent passage through shallow streams and swift navigation across broad lakes. These canoes were the SUVs of their era, essential for hunting, fishing, trade, and travel across the vast Wabanaki Confederacy territory. Every curve, every lash, every piece of bark tells a story of survival, adaptation, and an intimate understanding of the natural world.

The construction begins not in a workshop, but in the forest itself, with a reverent search for the right materials. The core, of course, is the birchbark – Betula papyrifera, the paper birch. Not just any bark will do. Builders seek out large, healthy trees, often mature specimens, with bark that is smooth, free of knots, and thick enough to be durable yet pliable. The ideal time for harvesting is spring, typically late May or early June, when the sap is running, allowing the bark to be peeled in large, flexible sheets without damaging the tree’s inner cambium layer. This is a delicate operation, requiring skill and respect to ensure the tree continues to thrive. A single canoe might require one massive sheet for the bottom and sides, or several carefully stitched pieces.

Complementing the birchbark are other vital forest offerings. White cedar (Thuja occidentalis) is the wood of choice for the canoe’s skeleton: the ribs, sheathing, gunwales, and thwarts. Cedar is prized for its lightness, remarkable flexibility when steamed, and natural resistance to rot, a crucial property for a watercraft. Its straight grain allows for easy splitting into long, thin strips. For the intricate lashing and sewing that binds the entire structure, spruce root (Picea spp.) is indispensable. Harvested from the forest floor, these roots are split, peeled, and soaked, becoming incredibly strong and flexible threads that swell when wet, creating a watertight seal. Finally, pine pitch or spruce gum, mixed with charcoal and animal fat, serves as the ultimate sealant, waterproofing every seam and stitch. This ancient sealant is remarkably durable and pliable, expanding and contracting with the wood and bark.

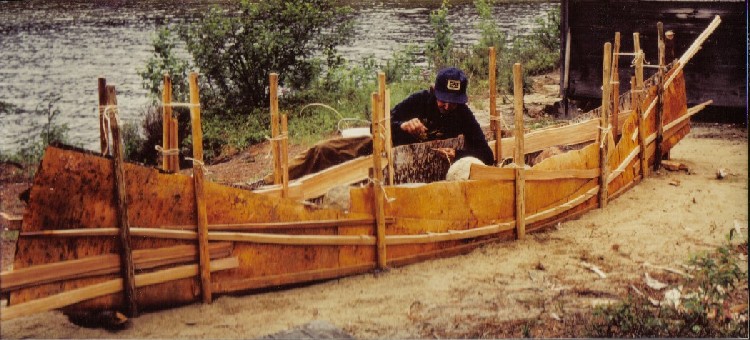

With materials gathered, the construction begins. The first step is to prepare the canoe bed, a flat, level area on the ground, often reinforced with logs or planks, which acts as a temporary building form. Stakes are driven into the ground around the perimeter, defining the canoe’s shape and dimensions – its length, beam, and tumblehome (the inward curve of the sides).

Next, the master bark sheet is laid, inner surface facing up, onto the canoe bed. If multiple pieces of bark are used, they are carefully overlapped and temporarily held in place. This is where the builder’s vision truly comes to life, as the flat sheet is coaxed into a three-dimensional form. Hot water or steam is applied to make the bark supple, allowing it to be bent and folded without cracking. The bark is then slowly, meticulously pulled up and over the stakes, its excess material at the ends gathered and folded to create the distinctive bow and stern profiles. This shaping process, often involving temporary braces and weights, is critical to achieving the canoe’s hydrodynamically efficient form. "You’re not just building a canoe; you’re coaxing a spirit from the forest," a Penobscot elder once remarked, emphasizing the organic nature of the process. "Every bend tells you what the tree wants to do."

Once the basic bark shell is formed, the intricate internal framework begins. The sheathing – thin, flexible cedar strips – is laid lengthwise along the inside bottom of the bark, providing a smooth surface and distributing pressure. Over this, the ribs are inserted. These cedar strips are first steamed until they are pliant, then bent into a U-shape, conforming precisely to the canoe’s hull. Each rib is carefully driven into place, creating the strong, resilient internal structure. The ribs are not merely functional; their spacing and curve contribute significantly to the canoe’s aesthetic and performance.

The gunwales are then added, forming the canoe’s top edge. These consist of an inner and outer strip of cedar, typically running the full length of the canoe. The bark is sandwiched between these two strips and then meticulously lashed together using the prepared spruce root. This lashing is a time-consuming but vital step, providing immense structural integrity and preventing the bark from tearing. The pattern of the lashing itself can be a subtle artistic expression.

The bow and stern are closed off with planking or hooding, usually made of cedar, which reinforces the ends and provides a finished look. Thwarts, or cross-braces, are installed between the gunwales to maintain the canoe’s width and add rigidity. Each component is fitted with exacting precision, often requiring custom shaping and careful adjustments.

Finally, the canoe is ready for its waterproofing. All seams, stitch lines, and points where the bark meets the gunwales or ends are coated with the heated pine pitch. This sealant, a black, sticky substance, is applied carefully, often with a small stick or spatula, ensuring every potential leak point is thoroughly sealed. The pitch not only makes the canoe watertight but also adds a distinctive dark sheen to its seams. It is the final act in transforming raw forest materials into a functional, beautiful vessel.

The entire process, from harvesting the bark to the final pitching, can take hundreds of hours, often spanning weeks or even months. It demands patience, deep knowledge of materials, exceptional hand-eye coordination, and an almost meditative focus. It is a craft that cannot be rushed, each step dependent on the successful completion of the last. "You listen to the wood, you listen to the bark," another builder might say. "It tells you what it needs."

Beyond the technical steps, building a Penobscot birchbark canoe is a profoundly cultural act. It represents the continuation of a living tradition, a tangible link to ancestors and a testament to the resilience of the Penobscot Nation. It teaches respect for the environment, emphasizing sustainable harvesting and a holistic view of resources. The knowledge is typically passed down orally and through hands-on apprenticeship, from elder to youth, ensuring the intricate details and subtle nuances of the craft are preserved. It fosters community, as multiple hands are often involved in various stages, sharing stories and wisdom alongside the work.

In recent decades, there has been a renewed interest in preserving and revitalizing traditional birchbark canoe building among the Penobscot and other Wabanaki communities. Master builders, often working with cultural centers and museums, lead workshops and demonstrations, ensuring that this invaluable heritage is not lost. Challenges remain, including the availability of suitable old-growth birchbark and the immense time commitment required in a modern world. Yet, the enduring beauty and practical genius of the birchbark canoe continue to inspire.

The Penobscot birchbark canoe is more than a historical artifact; it is a symbol of identity, adaptability, and the profound connection between a people and their environment. Each canoe that slides silently into the waters of the Penobscot River is a whispered prayer, a living story, and a powerful affirmation of an ancient way of life that continues to thrive and inspire. It reminds us that true innovation often lies in understanding and working with the natural world, rather than against it.