Beyond the Single Story: Reimagining Education for Turtle Island

For generations, the story of what is now known as North America – or Turtle Island, a name rooted in numerous Indigenous creation stories and cosmologies – has been told through a singular, often colonial lens. Educational institutions, products of settler societies, have historically perpetuated narratives that either erased, misrepresented, or exoticized Indigenous peoples, their histories, cultures, and knowledge systems. This pedagogical malpractice has inflicted profound damage, contributing to the systemic marginalization of Indigenous communities while leaving non-Indigenous students with a deeply incomplete and often harmful understanding of the land they inhabit.

Today, a paradigm shift is underway. Educators, institutions, and communities are increasingly recognizing the urgent need to decolonize the curriculum and embrace pedagogical approaches that genuinely reflect the richness, complexity, and sovereignty of Indigenous nations across Turtle Island. This isn’t merely about adding Indigenous content; it’s about fundamentally reshaping how we teach, what we value, and whose knowledge is centered in the learning process.

The Legacy of Erasure: Why Traditional Approaches Failed

The conventional teaching of Turtle Island has been characterized by several critical failures. First, it often presented Indigenous peoples as a monolithic entity, ignoring the astounding diversity of over 500 distinct nations in Canada and countless more in the United States, each with unique languages, governance structures, spiritual beliefs, and cultural practices. Second, it relegated Indigenous history to a distant past, often commencing with the arrival of Europeans and portraying Indigenous cultures as static or vanished, rather than vibrant, evolving, and contemporary.

Perhaps most damaging, traditional curricula frequently omitted or sanitized the brutal realities of colonization: the genocidal policies, the residential and boarding school systems designed to "kill the Indian in the child," the forced displacement, and the ongoing systemic discrimination. This "single story," as author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warns, creates stereotypes, robs people of their dignity, and makes true understanding impossible. For Indigenous students, this erasure often led to disengagement, identity crisis, and a sense of alienation within their own educational system. For non-Indigenous students, it fostered ignorance, perpetuated biases, and hindered their capacity for informed citizenship and genuine reconciliation.

Decolonizing the Classroom: Core Pedagogical Principles

The emerging pedagogical approaches to teaching Turtle Island are not prescriptive checklists but rather a commitment to ongoing learning, humility, and relationship-building. They are rooted in a decolonial framework that seeks to dismantle colonial structures of power and knowledge within education.

1. Centering Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS):

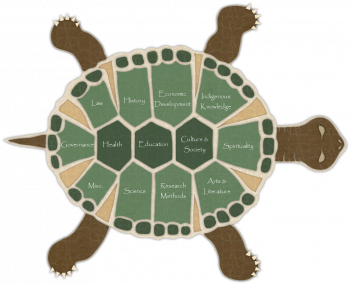

At the heart of this shift is the recognition that Indigenous peoples possess sophisticated, holistic knowledge systems developed over millennia. Unlike Western knowledge, which often compartmentalizes subjects, IKS are typically relational, experiential, and deeply connected to land, community, and spirit. Teaching Turtle Island effectively means moving beyond simply talking about Indigenous knowledge to actively teaching from Indigenous knowledge. This includes:

- Storytelling: Indigenous oral traditions are powerful pedagogical tools, conveying history, ethics, science, and law in engaging and culturally appropriate ways. Integrating Indigenous stories, myths, and contemporary narratives fosters critical listening and cultural understanding. As Anishinaabe scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson notes, "Stories are not just entertainment; they are the vessels through which Indigenous knowledge travels."

- Land-Based Learning: This approach emphasizes connecting students directly to the land as a teacher. It involves outdoor excursions, understanding local ecosystems from Indigenous perspectives, learning about traditional land use, food systems, and environmental stewardship. It grounds learning in place and fosters a profound respect for the Earth, reflecting Indigenous philosophies of reciprocal relationship with the natural world.

- Relationality: Indigenous pedagogies often emphasize the interconnectedness of all beings and the importance of relationships – with land, community, family, ancestors, and the spirit world. Educators are encouraged to foster a classroom environment that values collaboration, respect, and collective well-being over individualistic competition.

2. Integrating Indigenous Voices and Perspectives:

This involves a critical examination of existing curricula and actively seeking out and prioritizing Indigenous authors, artists, historians, scientists, and Elders. It means moving beyond a single "Native American unit" to weaving Indigenous perspectives throughout all subject areas – from history and literature to science, mathematics, and geography. For instance, studying Indigenous astronomical knowledge, complex pre-contact agricultural systems, or sophisticated governance structures like the Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace, showcases the intellectual depth and innovation of Indigenous societies.

3. Inviting Elders and Knowledge Keepers:

Elders and Knowledge Keepers are living libraries and vital carriers of cultural knowledge, language, and spiritual wisdom. Inviting them into the classroom, or arranging for students to visit them in their communities, provides invaluable opportunities for authentic learning and cultural exchange. It is crucial, however, that these interactions are conducted with the utmost respect, following community protocols, offering honoraria, and recognizing their intellectual property and spiritual authority. This practice directly addresses Call to Action #63 of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which emphasizes the need to build student capacity for intercultural understanding and empathy.

4. Culturally Responsive and Trauma-Informed Pedagogy:

For Indigenous students, culturally responsive teaching means creating a learning environment where their identities, languages, and experiences are affirmed and celebrated. This can significantly improve engagement, academic achievement, and a sense of belonging. Furthermore, educators must be aware of the historical and intergenerational trauma caused by colonization and residential schools. A trauma-informed approach prioritizes safety, trustworthiness, peer support, collaboration, empowerment, and cultural humility, ensuring that the classroom is a healing space rather than one that inadvertently re-traumatizes.

5. Fostering Critical Thinking and Challenging Stereotypes:

Effective teaching about Turtle Island empowers students to critically analyze information, deconstruct stereotypes, and identify bias in media and historical narratives. This involves engaging with difficult truths, exploring the complexities of historical events, and understanding the ongoing impacts of colonization. Students should be encouraged to question dominant narratives and develop their own informed perspectives.

Practical Strategies in Action

Implementing these pedagogical shifts requires more than good intentions; it demands deliberate action:

- Curriculum Audit and Redesign: Schools must critically review all learning materials for colonial biases, omissions, and stereotypes, replacing them with authentic Indigenous resources and co-developing curriculum with Indigenous educators and communities.

- Professional Development: Educators require ongoing training in Indigenous histories, cultures, pedagogies, and anti-racism. This is not a one-time workshop but a continuous journey of learning and unlearning.

- Community Partnerships: Building genuine, respectful relationships with local Indigenous communities is paramount. This can lead to shared learning opportunities, cultural exchanges, and collaborative projects.

- Language Revitalization: Even basic introductions to local Indigenous languages can foster respect and understanding, and for Indigenous students, it can be a vital connection to their heritage.

- Art, Music, and Media: Integrating Indigenous artistic expressions – contemporary and traditional – provides powerful avenues for understanding culture, history, and resilience.

Challenges and the Path Forward

The journey towards decolonized education is not without its challenges. Teacher preparedness remains a significant hurdle; many educators have not received adequate training in Indigenous studies. Access to high-quality, culturally appropriate resources can be limited, particularly in remote areas. Furthermore, addressing resistance or discomfort from some students, parents, or even colleagues who may be entrenched in colonial mindsets requires patience, education, and unwavering commitment. It is crucial to avoid tokenism or superficial inclusion, ensuring that Indigenous content is integrated meaningfully and respectfully, not merely as an add-on.

Ultimately, reimagining pedagogical approaches to teaching Turtle Island is about truth, justice, and reconciliation. It is about acknowledging the full, complex history of this land and its peoples. For Indigenous students, it offers a pathway to affirmation, empowerment, and a stronger sense of identity. For non-Indigenous students, it cultivates empathy, critical consciousness, and the skills needed to become responsible, respectful citizens who contribute to a more just and equitable society. As we move forward, the classroom must become a space where all stories are heard, all knowledge is valued, and the rich, diverse tapestry of Turtle Island can finally be understood in its full, vibrant truth. The future of education, and indeed of our shared communities, depends on it.