The Ancient Pulse: Unraveling the Painted Turtle’s Enduring Lifecycle on Turtle Island

On Turtle Island, the vast expanse of North America, where ancient waterways weave through forests and plains, a quiet, resilient sentinel has navigated the seasons for millennia. The painted turtle (Chrysemys picta), with its striking red and yellow markings adorning a dark carapace, is not merely a common sight; it is a living testament to endurance, an emblematic figure whose lifecycle mirrors the very pulse of the land itself. From the depths of icy ponds to the warmth of sun-drenched logs, its journey through life is a marvel of adaptation, a saga of survival etched into the fabric of this continent.

The Great Awakening: Spring’s Embrace

As winter’s grip loosens and the first whispers of spring warm the waters, the painted turtle stirs from its profound slumber. This period, known as brumation, sees the turtle buried in the muddy bottoms of ponds, lakes, or slow-moving rivers, its metabolism drastically slowed, surviving on minimal oxygen. The emergence is a slow, deliberate process. Driven by rising water temperatures and the lengthening daylight, these reptiles, often caked in mud, ascend to the surface. Their first priority: to bask.

Basking is not a leisure activity but a critical physiological necessity. Stretching out on logs, rocks, or sandy banks, painted turtles absorb the sun’s warmth, raising their body temperature to optimal levels for digestion, immune function, and the synthesis of Vitamin D. This thermoregulation is vital, preparing their bodies for the arduous tasks of mating and nesting that lie ahead. Their vibrant markings, often obscured during brumation, now gleam under the spring sun, a beautiful herald of renewed life.

The Courting Ritual: A Dance of Delicacy

With their systems primed by the sun, the focus shifts to reproduction. Late spring and early summer bring forth the painted turtle’s unique courtship ritual. Males, often smaller than females and distinguished by their elongated foreclaws, approach prospective mates. The male positions himself facing the female, extending his long claws and vibrating them rapidly against the sides of her head and neck. This delicate, almost hypnotic tactile display, believed to stimulate the female, is a silent invitation to mate.

If receptive, the female allows the male to mount her from behind, a process that can take several hours. Internal fertilization occurs, and the female then retains the fertilized eggs for a period, preparing for the demanding journey of nesting. This intimate interaction, hidden beneath the water’s surface, is a crucial link in the chain of life, ensuring the continuation of the species.

The Nesting Odyssey: A Perilous Trek

The female’s most vulnerable and critical act begins shortly after mating. Driven by an innate instinct, she embarks on a quest for the perfect nesting site. This often involves leaving the relative safety of the water and venturing onto land, sometimes traveling considerable distances across challenging terrain. The ideal location is typically sunny, well-drained soil, often sandy or loamy, providing sufficient warmth for incubation and protection from waterlogging.

Using her powerful hind legs, the female meticulously digs a flask-shaped chamber, a testament to her anatomical design and ancient wisdom. The digging can take hours, a slow, deliberate excavation of her future progeny’s nursery. Once the nest is complete, she deposits a clutch of 2 to 20 elliptical, leathery-shelled eggs. Each egg is carefully positioned within the chamber. After laying, she painstakingly covers the nest with soil, compacting it with her plastron (bottom shell) and using her hind legs to scatter debris, camouflaging the site as best as possible. Exhausted, she then returns to the water, leaving her offspring to the mercy of the elements and fate. This solitary act underscores the profound maternal investment without any further parental care.

Incubation and the Mystery of TSD

The incubation period for painted turtle eggs typically ranges from 60 to 90 days, largely dependent on ambient temperature. And it is temperature that holds a fascinating secret: the sex of the hatchlings. Painted turtles exhibit Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination (TSD), a remarkable biological mechanism. Generally, cooler temperatures during a critical period of incubation lead to the development of males, while warmer temperatures produce females. This phenomenon, sometimes summarized as "hot mamas, cool papas," highlights the profound influence of environmental conditions on population dynamics.

However, the journey within the nest is fraught with peril. The eggs are vulnerable to a host of predators, including raccoons, skunks, foxes, and various birds, all adept at sniffing out freshly laid clutches. Heavy rains can flood nests, and prolonged droughts can dehydrate the developing embryos. Only a fraction of the eggs laid will ever make it to hatching.

Hatchling Emergence: A Tiny Battle for Survival

The moment of hatching is a miniature struggle for life. Equipped with a tiny, temporary "egg tooth" on their snouts, the hatchlings meticulously cut through their leathery shells. Once free, they face a critical decision: emerge immediately or overwinter in the nest. In many northern regions of Turtle Island, hatchlings possess an extraordinary adaptation: they can survive freezing temperatures within the nest, effectively spending their first winter underground. Their bodies produce cryoprotectants, allowing them to endure the cold until spring’s warmth signals a safer emergence. This remarkable ability showcases the species’ deep-seated resilience to the harsh North American climate.

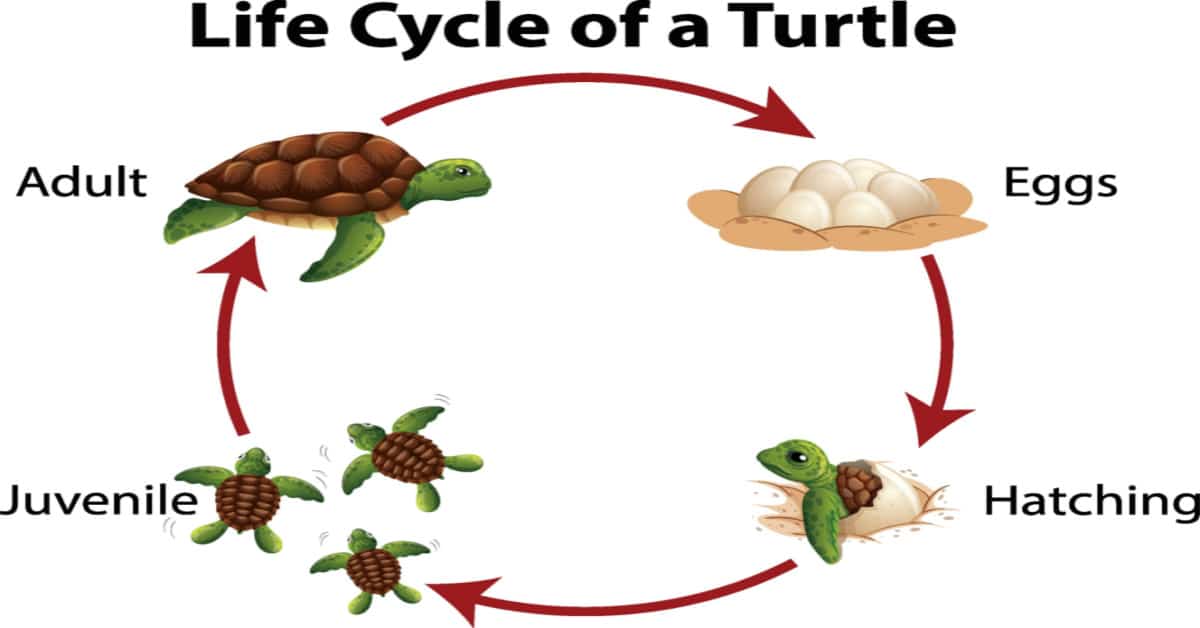

Whether emerging in fall or spring, the newly hatched turtles, barely larger than a quarter, are incredibly vulnerable. Their journey from the nest to the water is a gauntlet of dangers. Predators lie in wait: birds of prey, snakes, larger frogs, and even fish once they reach the water. The first few days and weeks of a hatchling’s life are the most perilous, with survival rates often less than 1%. Those that make it to water immediately begin to feed, consuming small insects, aquatic vegetation, and detritus, driven by an urgent need to grow.

Growth, Adulthood, and the Cycle’s Renewal

For the survivors, the juvenile stage is a period of rapid growth. They shed their scutes (the plates on their shell) as they grow, much like snakes shed their skin. Their diet diversifies, including a mix of insects, larvae, small fish, carrion, and aquatic plants. This omnivorous diet allows them to adapt to available food sources and contributes to their role as important components of wetland ecosystems, helping to keep waterways clean by scavenging and dispersing seeds.

Painted turtles typically reach sexual maturity between 2 to 5 years for males and 4 to 8 years for females, depending on environmental conditions and food availability. Once mature, they can live for 20 to 50 years in the wild, continuously contributing to the reproductive cycle. Their longevity is a testament to their robust physiology and their ability to withstand environmental fluctuations. Throughout their adult lives, they continue their seasonal rhythm: basking, feeding, mating, nesting (for females), and eventually, retreating to brumation as winter approaches, ready to repeat the ancient cycle.

Threats and the Future of an Icon

Despite their remarkable resilience, painted turtles face increasing threats across Turtle Island. Habitat loss and fragmentation due to urbanization, agriculture, and road construction are paramount concerns. Wetlands, their primary habitat, are continually drained or degraded. Road mortality is a significant issue, particularly for nesting females traversing land. Pollution, invasive species, and the emerging impacts of climate change, which can skew sex ratios due to TSD, further compound their challenges.

Conservation efforts, including wetland protection, road crossing structures, and public education, are vital to ensure the painted turtle’s continued presence. They are not just beautiful creatures; they are indicator species, their health reflecting the health of the aquatic ecosystems they inhabit.

An Enduring Symbol of Turtle Island

The painted turtle’s lifecycle is a microcosm of the enduring spirit of Turtle Island. From the silent, frozen dormancy of winter to the vibrant, life-affirming activities of summer, its journey is a powerful narrative of adaptation, vulnerability, and perseverance. It is a creature that has witnessed millennia of change, its patterns of life intricately woven into the natural rhythms of this continent. As we observe the painted turtle basking on a log, or watch a tiny hatchling brave its first journey to water, we are not just witnessing a reptile; we are observing an ancient pulse, a living symbol of resilience that reminds us of our interconnectedness with the natural world and our responsibility to protect its timeless cycles for generations to come. The painted turtle, in its quiet determination, continues to paint its story across the waters and lands of North America, a vibrant, enduring masterpiece.