Seeds of Civilization: The Indigenous Agricultural Revolution of the Americas

Imagine a world without potatoes, tomatoes, corn, or chili peppers. A world where chocolate and vanilla are unknown luxuries, and beans, squash, and peanuts are absent from our plates. This unimaginable culinary landscape would be our reality were it not for the ingenious agricultural innovations of Indigenous peoples across the Americas, who, over millennia, transformed wild plants into the foundational crops that now feed billions worldwide. Far from a singular event, the origins of agriculture in the Americas represent a mosaic of independent discoveries and adaptations, a testament to human ingenuity in diverse ecological zones, from arid deserts to high mountain plateaus and dense tropical forests.

The story begins not with plows and vast fields, but with careful observation, deep ecological knowledge, and a patient, reciprocal relationship with the land. For thousands of years after the first human migrations into the continents, hunter-gatherer societies thrived, navigating complex landscapes and understanding the rhythms of nature. Yet, sometime around 9,000 to 10,000 years ago, a profound shift began to unfold in various pockets of the Americas, marking the dawn of an agricultural revolution that would dramatically reshape human societies, paving the way for villages, cities, empires, and an unparalleled explosion of cultural complexity.

The Mesoamerican Miracle: The Staff of Life

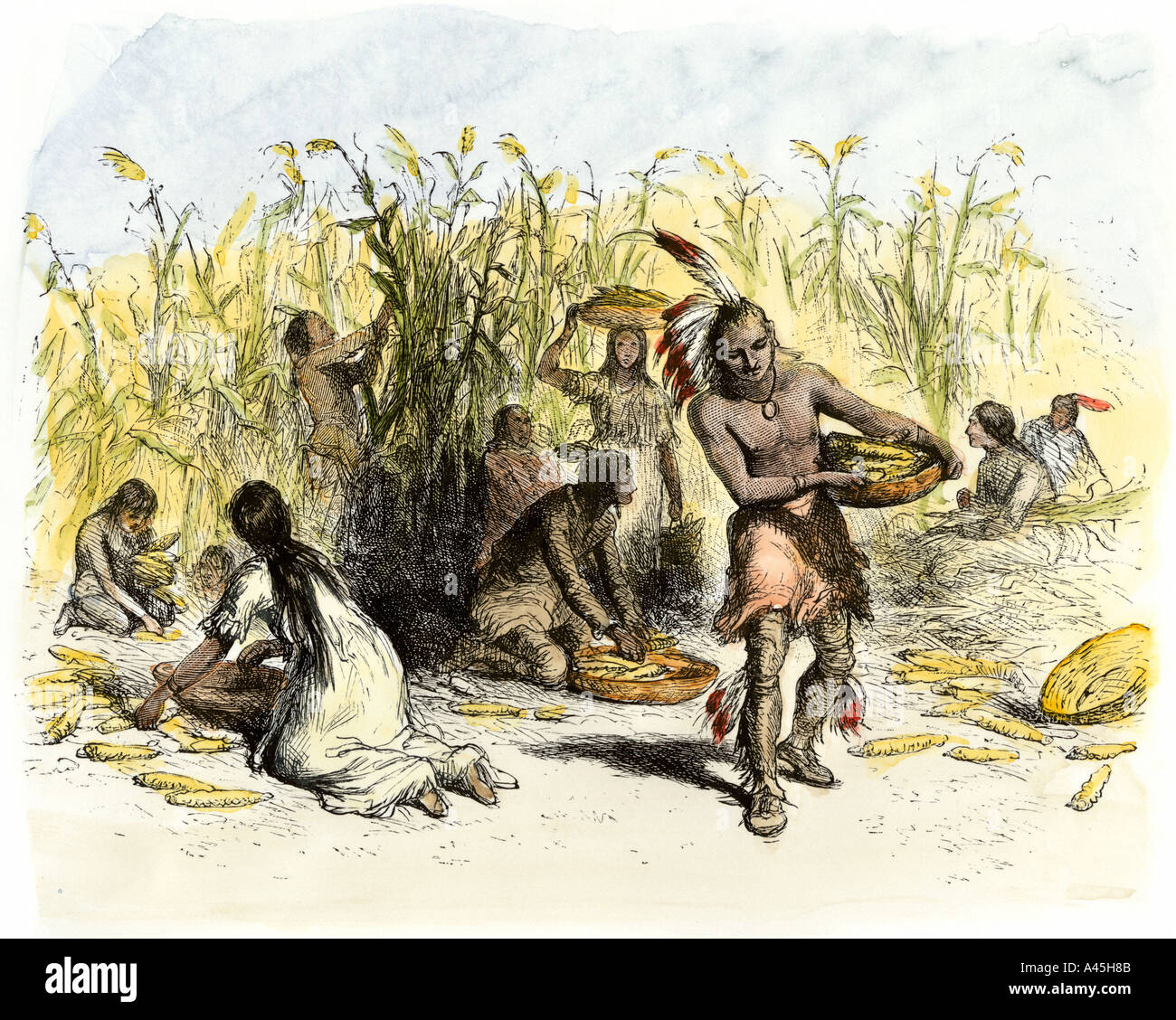

Perhaps the most iconic agricultural achievement of the Americas is the domestication of maize (corn) in Mesoamerica, a region encompassing modern-day Mexico and parts of Central America. This staple crop is a genetic marvel, a dramatic transformation from its wild ancestor, teosinte, a grassy plant with small, hard kernels barely resembling the plump, juicy ears we know today.

Archaeological evidence, particularly from the Balsas River Valley in southwestern Mexico, points to teosinte’s domestication around 9,000 years ago. This wasn’t an overnight revelation but a gradual, painstaking process of selective breeding. Early farmers likely noticed mutations that made teosinte kernels larger, softer, or more easily harvested, and consciously chose to replant seeds from these advantageous variants. Over generations, human selection guided teosinte’s evolution, fundamentally altering its genetic structure to produce a plant that became entirely dependent on humans for its survival and propagation.

The impact of maize was nothing short of revolutionary. "Maize wasn’t just a food; it was the very backbone of Mesoamerican civilization," notes Dr. Elena Rodriguez, an archaeobotanist specializing in ancient American agriculture. "Its high caloric yield allowed for unprecedented population growth, leading directly to the development of sedentary villages, monumental architecture, complex social hierarchies, and sophisticated belief systems." Maize became central to the cosmology of cultures like the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec, often depicted as a deity or the source of human life itself, as recounted in the Maya creation myth, the Popol Vuh, where humans are fashioned from maize dough.

Alongside maize, Mesoamericans also domesticated a suite of other crucial crops, including beans and squash. The symbiotic relationship between these "Three Sisters"—corn providing a stalk for beans to climb, beans fixing nitrogen in the soil, and squash leaves shading the ground to retain moisture and suppress weeds—is a testament to the sophisticated ecological understanding of Indigenous farmers. Chili peppers, avocados, tomatoes, and cacao (the source of chocolate) also originated in this fertile cradle, enriching the diets and cultures of the region and eventually the entire world.

The Andean Abundance: Masters of Altitude

South America’s Andean region, with its stark contrasts of high-altitude plateaus and fertile valleys, presents another extraordinary chapter in agricultural innovation. Here, Indigenous peoples domesticated a diverse array of plants uniquely adapted to challenging environments, with the potato standing as its most enduring legacy.

Originating in the Lake Titicaca region of the high Andes, the potato was domesticated around 8,000 to 10,000 years ago. Unlike the monoculture fields of modern agriculture, Andean farmers cultivated thousands of varieties of potatoes, each adapted to specific microclimates, soil types, and resistance to pests and diseases. This incredible biodiversity was a critical safeguard against crop failure and ensured food security in an unpredictable environment. Some varieties were specifically bred for their ability to withstand frost, others for their storability.

The Inca Empire, which would later rise to prominence in the Andes, managed a sophisticated agricultural system built upon these ancient foundations. Their engineering prowess was evident in extensive terracing systems carved into mountainsides, creating flat, arable land and microclimates that extended growing seasons. They also employed advanced irrigation techniques and experimented with waru waru, or raised-field agriculture, which involved constructing elevated planting beds surrounded by water-filled canals. These canals absorbed solar radiation during the day and radiated heat at night, protecting crops from frost and simultaneously providing a habitat for fish, which fertilized the fields.

Beyond the potato, Andean peoples gave the world quinoa, a highly nutritious grain-like seed; sweet potatoes; ulluco, oca, and maca, other root crops; and numerous varieties of beans and gourds. These high-altitude agriculturalists demonstrated an unparalleled ability to harness the potential of seemingly inhospitable landscapes, turning mountains into bountiful food producers.

Beyond the Staples: A Continent of Cultivation

The agricultural narrative of the Americas extends far beyond maize and potatoes, encompassing a vast tapestry of domestication events across the continent.

In the Amazon basin, Indigenous groups mastered the cultivation of manioc (cassava), a starchy root crop that, in its wild form, contains cyanide. Through ingenious processing techniques involving grating, pressing, and heating, Amazonian peoples developed methods to remove the toxins, transforming a dangerous plant into a reliable and calorie-rich staple that could be stored for long periods. This mastery of detoxification speaks volumes about their botanical knowledge and chemical understanding.

North America also saw independent agricultural developments. In the Eastern Woodlands, Indigenous communities began cultivating local plants like sunflower, sumpweed (Iva annua), and goosefoot (Chenopodium) around 4,500 years ago, long before the widespread adoption of Mesoamerican maize. These "Eastern Agricultural Complex" plants provided valuable sources of oil and carbohydrates, demonstrating a localized, independent path to agriculture adapted to temperate forest environments. Later, the Mississippian cultures, known for their monumental mound building, integrated maize into their existing agricultural systems, leading to further population growth and the development of vast trade networks.

In the arid Southwest, Ancestral Puebloans and Hohokam peoples engineered complex irrigation canals to divert water from rivers, transforming deserts into productive fields where they cultivated maize, beans, and squash, building communities that flourished for centuries in challenging conditions.

The Enduring Legacy and Lessons for Today

The agricultural revolution of Indigenous Americas was not a singular event but a testament to humanity’s adaptive genius. It was driven by diverse communities, each responding to their unique ecological challenges and opportunities, fostering a profound connection to the land and its resources. This process of domestication was inherently a process of co-evolution, where humans shaped plants, and plants, in turn, shaped human societies, diets, and cultures.

When Europeans arrived in the Americas, they encountered not a wilderness, but a continent teeming with sophisticated agricultural systems and an astonishing diversity of cultivated plants. The subsequent "Columbian Exchange" introduced these crops to the rest of the world, triggering a global food revolution. Maize, potatoes, tomatoes, beans, squash, chili peppers, and many other American crops became fundamental to diets across Europe, Africa, and Asia, contributing to massive population increases and profoundly altering global cuisines and economies.

Today, as we face the challenges of food security, climate change, and biodiversity loss, the ancient wisdom of Indigenous agriculture offers invaluable lessons. The emphasis on biodiversity, ecological understanding, sustainable practices like polyculture (planting multiple crops together), and adaptive ingenuity are more relevant than ever. The Indigenous peoples of the Americas not only fed their own civilizations but laid the groundwork for feeding the world, leaving an enduring legacy that continues to shape our plates and our planet. Their story is a powerful reminder of the deep, often unacknowledged, debt the modern world owes to the agricultural brilliance of its first farmers.