The Eternal Flame: Onondaga Nation’s Central Fire, A Living History of Sovereignty and Resilience

In the heart of what is now upstate New York, amidst the rolling hills and ancient forests, lies a sacred locus, a spiritual and political hearth that has burned, metaphorically and often literally, for millennia. This is the home of the Onondaga Nation, the "Keepers of the Central Fire," a title that transcends mere geography to embody their profound role within the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy. The Central Fire is not just a historical relic; it is a living, breathing testament to enduring sovereignty, cultural resilience, and an unwavering commitment to the Great Law of Peace.

To understand the Onondaga’s Central Fire is to delve into the very genesis of one of North America’s most sophisticated Indigenous democracies. Long before European contact, the Haudenosaunee, comprised originally of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca Nations, were locked in cycles of brutal intertribal warfare. It was during this tumultuous period, according to oral tradition, that the Great Peacemaker and Hiawatha brought forth the message of the Great Law of Peace, or Gayanashagowa. This revolutionary constitution, founded on principles of peace, power, and righteousness, united the warring nations under a single, overarching government symbolized by the Great Tree of Peace.

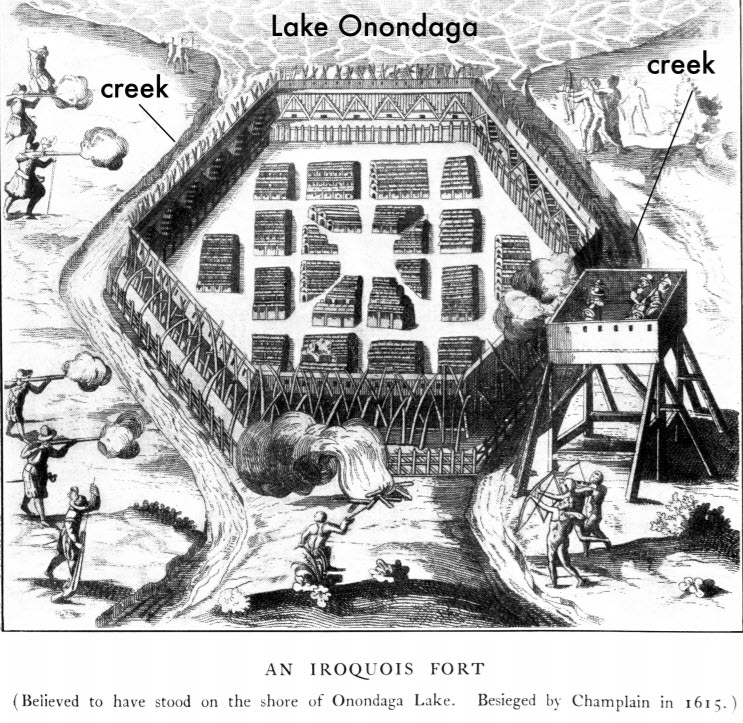

The Onondaga Nation was designated as the literal and metaphorical "Central Fire" of this nascent Confederacy. Their territory, situated centrally within the traditional lands of the Five Nations, became the meeting place for the Grand Council. Here, at Onondaga Lake, the fifty paramount chiefs, or Hoyaneh, would gather under the shelter of the Great Longhouse, its ends open to the rising and setting sun, to deliberate on matters affecting the entire Confederacy. The Onondaga’s role was unique: they held the Wampum belts – intricate shell bead records that chronicled the laws, treaties, and history of the Haudenosaunee – and were responsible for opening and closing the council meetings. Their Tadodaho, the supreme spiritual and political leader of the Confederacy, held the heaviest responsibility, acting as the firekeeper and ensuring the sacred flame of unity never faltered.

"The Central Fire," as Onondaga Chief Sid Hill often explains, "is where our ancestors gathered, where the Great Law was spoken, and where decisions for the entire Confederacy were made. It represents the heart of our people, the warmth of our families, and the light of our governance. It is a place of profound responsibility and enduring presence."

This sacred fire, whether a physical hearth in a council longhouse or the enduring spirit of governance, was the crucible where diplomacy was forged, disputes were resolved, and collective identity was reaffirmed. The Onondaga people became skilled mediators, their voices often the last to be heard in council debates, ensuring that all perspectives were considered before a consensus was reached. This democratic process, with its emphasis on careful deliberation and the eventual unanimity of mind, profoundly influenced later democratic thought, even inspiring some of the American Founding Fathers. Benjamin Franklin himself noted the efficacy of the Iroquois system, wondering why the colonies couldn’t achieve a similar unity.

The arrival of European powers in the 17th century brought immense challenges to the Central Fire. French, Dutch, and later British colonial ambitions carved up the continent, often viewing Indigenous lands as empty territories ripe for conquest. The Haudenosaunee, through the Onondaga’s Central Fire, engaged in complex diplomacy, forging alliances and treaties – most notably the Guswenta, or Two Row Wampum Treaty, with the Dutch in 1613. This pivotal agreement, symbolized by two parallel rows of purple beads on a white background, represented two vessels – the Native canoe and the European ship – traveling side-by-side down the river of life, each respecting the other’s laws, customs, and sovereignty, never attempting to steer the other’s vessel. It was a foundational assertion of distinct nationhood, negotiated from the heart of the Confederacy.

Yet, despite such efforts, the encroaching tide of colonialism proved relentless. The American Revolution was particularly devastating. The Confederacy, attempting to maintain neutrality, was ultimately split, with some nations siding with the British and others with the rebellious colonies. The Onondaga, striving to hold the Central Fire together, found their traditional lands ravaged by Sullivan’s Expedition in 1779, a scorched-earth campaign that destroyed villages, crops, and the very symbols of their communal life. The physical flames of their hearths were extinguished, but the spiritual fire of their governance persisted.

In the aftermath of the Revolution, the Onondaga, like other Haudenosaunee nations, found their land base drastically reduced through a series of treaties, often signed under duress or by individuals not authorized by the Grand Council. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1784 and subsequent agreements saw millions of acres ceded, pushing the Onondaga onto a fraction of their ancestral domain. Despite these losses, the Central Fire continued to burn. The Grand Council meetings, though often held in secret or under difficult circumstances, never ceased. The Tadodaho continued to be chosen, the Wampum belts continued to be recited, and the Great Law of Peace remained the guiding principle for the Onondaga people.

The 19th and 20th centuries presented new forms of assault. The imposition of federal and state laws, the establishment of residential and boarding schools designed to "kill the Indian in the child," and the relentless pressure to assimilate all aimed to extinguish the Central Fire of Indigenous identity and self-governance. Children were forbidden to speak their language, practice their ceremonies, or learn their traditions. Yet, in quiet acts of defiance and resilience, the Onondaga elders continued to pass down the stories, the language, and the responsibilities of the Central Fire. The traditional government, though often unrecognized by external powers, continued its sacred duties, maintaining the internal sovereignty of the Nation.

One of the most profound examples of the Central Fire’s enduring spirit lies in the Onondaga Nation’s ongoing struggle for environmental justice and land stewardship. Their ancestral territory includes Onondaga Lake, once pristine, but for decades considered one of the most polluted lakes in America due to industrial dumping by companies like Allied Chemical (now Honeywell). For the Onondaga, the lake is not merely a body of water; it is a sacred relative, a provider, and a vital part of their identity. Their efforts to heal the lake, to demand accountability, and to participate in its restoration are a direct expression of their responsibilities as Keepers of the Central Fire – a commitment to the seventh generation, ensuring a healthy environment for those yet to come.

As Tadodaho Sidney Hill has often stated, "Our responsibility is to the land, to the water, to the air, to the animals, to the next seven generations. We are not just fighting for ourselves, but for all life on Mother Earth. This is what the Central Fire teaches us."

In the 21st century, the Onondaga Nation continues to assert its inherent sovereignty on both national and international stages. They have filed land rights actions, seeking not to dispossess current landowners but to gain recognition of their aboriginal title and secure funding for environmental remediation and cultural revitalization. They actively participate in the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, sharing their governance model and advocating for Indigenous rights globally. Their Longhouse remains the vibrant center of their community, where ceremonies are held, the language is taught, and the principles of the Great Law are lived daily.

The Central Fire of the Onondaga Nation is more than just a historical footnote; it is a dynamic, living entity. It represents the unbroken chain of traditional governance, the perseverance of a distinct culture, and an unwavering commitment to the principles of peace and respectful coexistence. It is a beacon that has guided the Onondaga through millennia of change, conflict, and challenge. And as long as the Onondaga people walk their ancestral lands, honoring their responsibilities to the land and to the Great Law, the Eternal Flame of their Central Fire will continue to burn brightly, illuminating a path of sovereignty and resilience for generations to come.